We human beings like to think of ourselves as wise, as homo sapiens. But we share two of our most common qualities with the beasts. We are often murderous, and hence have been described as homo necans in a disquisition on violence (in relation to Greek sacrificial rites and myths) published under that title by Walter Burkert. And we are irrepressibly playful, as documented in Jan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens.

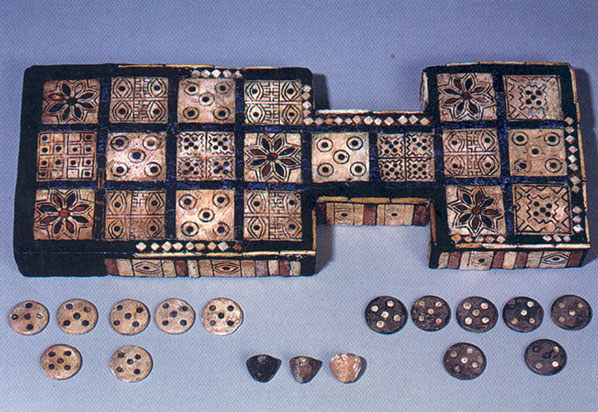

Evidence of this universal playfulness goes deep into the past. Surprisingly, some of its manifestations have stayed recognizably similar over the millennia, such as dice and board games.

It may seem odd that so specific a phenomenon as dice should have its origin in antiquity, and yet that is true not only of the concept but of the precise form. The earliest dice known date to the second half of the third millennium B.C.E.; they come from the Indus Valley culture, in present-day Pakistan, and from Mesopotamia in the Early Dynastic III period (c. 2500–2300 B.C.E.). These ancient specimens look very much like modern dice, and some of them have dots arranged in the modern way (with dots on opposite sides adding up to seven). The Mesopotamians continued to play with dice in the second and first millennia B.C.E.; a late example from Babylon is even made of glass. Further west, in Palestine and Egypt, various shapes were experimented with, but the “modern” cubical shape and dot arrangement is also attested, for example in dice recovered in excavations at Ashkelon.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address.