There is no West without Homer. So perhaps it is not surprising that the two most important 20th-century contributions to the study of classics—made by the American scholar Milman Parry (1902–1935) and the British architect Michael Ventris (1922–1956)—were also important contributions to our understanding of Homer.

Parry’s intense, romantic life—partly spent studying Slavic oral poetry in the Balkans—came to an end when he shot himself in a hotel room in Los Angeles after being denied tenure at Harvard. His groundbreaking achievement was to demonstrate that the style of Homer’s epics is utterly unlike that of a poet like Virgil (or Milton, or Tennyson, or Yeats), who composed in writing. Parry proved that the Iliad and Odyssey were composed orally—as great stories, or songs, assembled from smaller fragments and only later written down.

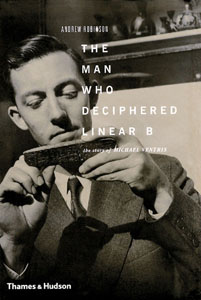

Like Parry, Michael Ventris died at a shockingly young age in troubling circumstances. One night, he drove his car full speed into a well-lighted parked truck. This was indeed a loss to scholarship and human knowledge. Ventris, although not a classicist, had accomplished one of the most brilliant decipherments ever, showing the world that an obscure script called Linear B was used to write the Mycenaean Greek language. He thus opened a window of understanding (if a narrow one) onto the lives of the Greeks who lived around the time of the Trojan War (if there was a Trojan War).

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address.