Israel Enters Canaan—Following the Pottery Trail

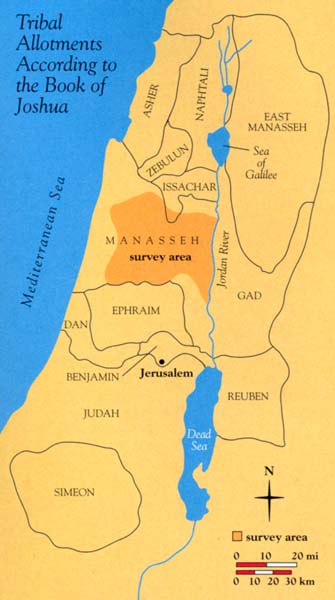

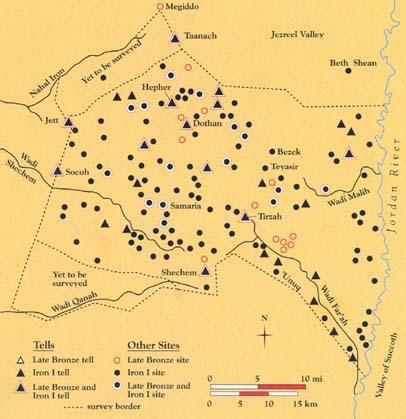

After 12 years of surveying and excavating in the land allotted in the Bible to the tribe of Manasseh, it is now possible to suggest new ideas on the emergence of Israel in Canaan, beginning at the end of the Late Bronze Age (13th century B.C.E.a) and continuing into Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.E.).

Using the results of a detailed archaeological survey and one large-scale excavation on Mt. Ebal, and with the aid of recent statistical models and computer-generated analyses, combined with a reexamination of Biblical texts and results achieved and accumulated in neighboring areas, we can now treat crucial questions such as: Where did the Israelites who first appear in the land of Canaan come from? What path did their settlement take? What was their relationship to the Canaanite population? How did their religion develop?

These are some of the most controversial issues currently being debated by Biblical archaeologists and Biblical historians. In the last 50 years or so, three different basic models have been proposed for Israel’s emergence as a people in Canaan: (1) the conquest model, often associated with the American Biblical archaeologist, William F. Albright; (2) the peaceful-infiltration model, often associated with the German Biblical historian Albrecht Alt; and (3) the peasant-revolt or social-revolution model, first proposed by the American Biblical scholar George Mendenhall and further developed by another American Biblical scholar, Norman Gottwald. Each of the three theories has difficulties, especially when one tries to ground them archaeologically.

Albright based his conclusions regarding an Israelite conquest of Canaan on the results of excavations in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. He attempted to correlate the archaeological evidence of site destructions with the Biblical text, primarily the Book of Joshua. At the time Albright developed his proposal, archaeology was struggling to become a more scientific discipline with a sound excavation methodology; today we do not always understand the excavation results as Albright understood them. It is no longer so easy to associate directly a series of destructions with the Book of Joshua or some other Biblical text. Alt’s theory that the Israelites penetrated peacefully into unoccupied areas of the hill country of central Canaan was based largely on a shrewdly nuanced reading of the Biblical texts, mainly Joshua and Judges, although with some use of other sources. Alt, I believe, was far ahead of his time in understanding the historical and sociological processes involved in the Israelite settlement. His theory was later tested archaeologically by Israeli archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni, who in 1957 conducted a survey in the upper Galilee and found evidence of what he regarded as a centuries-long peaceful settlement process there. But Alt’s thesis related mainly to the central hill country, where no archaeological material was yet available.

Drawing on modern anthropological and sociological concepts, beginning in the mid-1960s, Mendenhall and later Gottwald identified most of the early Israelites not as outsiders who came into the land, but as Canaanite renegades who revolted against their feudal urban oppressors. Leaving the Canaanite cities in the western part of the country and in the Valley of Jezreel, the Canaanite underclass fled east and south to the central hill country, according to these theorists. In short, Israel emerged from within Canaan, not from outside it. Perhaps with some justification, Mendenhall—and, to some extent, Gottwald also—placed little reliance on archaeology, regarding it as too fragile a science to lean upon.

In truth, even today archaeology lies somewhere in that vague no-man’s-land between the natural sciences and the humanities. Although archaeology uses some modern technologies, many of its conclusions are drawn on the basis of intuition, rather than on objective measure. The quality of excavation, surveying and publication of results is very uneven. Excavation methods are rarely agreed upon. And when it cannot depend on reliable historical sources to interpret the results, archaeology sometimes becomes a mere technical investigation of material culture. Even with such sources at hand, controversies concerning the results often develop: One observer, for example, may say a stratum was destroyed in 900 B.C.E., another places the destruction at 800 B.C.E., and a third claims the site was peacefully abandoned! Alas, a lack of financial resources also leaves archaeology far behind other sciences. Finally, even when archaeology is done well, reading an archaeological report, if one has been published, can be daunting; it is easy to be overwhelmed by the number of hypotheses, suppositions and presuppositions, supported—or not—by a mass of data. So Biblical historians often simply ignore the archaeological materials.

All of these factors have played a part in the discussion of Israel’s emergence in Canaan. For example, how do you tell whether a site like Giloh,1 just outside of Jerusalem, was an Israelite, a Jebusite or a Canaanite village? How do you tell whether Iron Age Ai was Israelite or Hivite? Can anybody demonstrate who was Israelite, or even what it meant to be an Israelite in the 12th century B.C.E.?

Nevertheless, with more recently developed statistical methods, aided by the computer, which helps us to ask and answer new questions, I believe it is now possible to advance at least one step forward toward a synthesis that better integrates the archaeological results.

We begin with the raw material that has accumulated over a 12-year period in our archaeological survey of the territory of Manasseh.b Our survey team has examined every wadi,c spring, terrace, hill slope and olive grove. The fact that a single survey team undertook this project provides special advantages: There is one methodology, and the results are recorded in the same way, without overlapping or the need to try to compare apples and oranges. Moreover, the survey studied not only the sites, the man-made installations, scattered potsherds and worked flints, but also the ecological and environmental factors. And the survey team analyzed this mass of material with the aid of a computer.

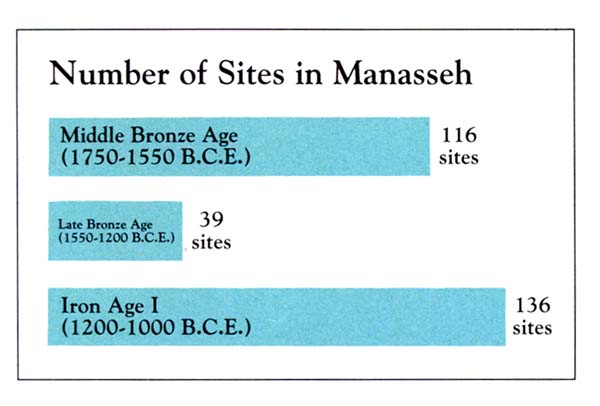

We were lucky to have chosen Manasseh for this study. The territory of Manasseh has a special relevance to the problems that concern us. Although unaware of this when we started, it soon became evident that the territory of Manasseh is one of the archaeologically richest in the hill country of Canaan. As a result of natural conditions (water, fertile soil and important trade routes), Manasseh’s territory was heavily populated with sites and human civilizations. For example, 39 sites from the Late Bronze Age (the Canaanite period) were found in Manasseh; in Ephraim there were only five, although both territories are equal in area.

With some simple basic principles in mind, we began the survey in 1978. Those principles consisted of completely surveying the territory by foot, choosing a tribal territory as the basic unit of our survey, examining historical periods before and after the periods of our special interest and, above all, seriously involving the science of ecology.

We began with the decision to analyze ecological and archaeological facts first, and only later to consult the Bible. Underlying our first steps was the assumption that ecology is more objective than history, or at least that it can widen historical horizons. The ecological facts are there. For the most part they have not changed.2 In general, different observers will be able to agree on what the ecological facts are. This is not so easy to do with history.

Moreover, humans adapt to their environment. By studying it, we can learn a great deal about human society, economy and even religion. Thus by studying this environment, we can better understand history. This idea is hardly new, but it had not yet been used to study the Israelite settlement process in a specific large territory that was crucial for understanding Israel’s emergence in Canaan.

The plan was to study the sites in the territory of Manasseh by examining the environment of each site and then relating each site to the other sites from the same period. The information from each site, including environmental factors, was computerized, enabling us to analyze the interrelationships among different sites.

Let me be more specific. First, we examined the site’s name, or names, which sometimes bore a relationship to its Biblical name (like Arrabeh and Arubboth [1 Kings 4:10] and like Ibziq and Bezeq [Judges 1:4–5], etc.). Then we recorded its location on two coordinates of our grid. We also recorded its elevation above sea level and above the surrounding area. We recorded the type of site—its size, its topography, its geology and geomorphology (that is, the forms of the different rocks and mountains). We noted the type and quality of soil, whether it was presently being cultivated and, if so, for what crops. For each site, we asked how near the site was to a water source and what the water source was, how far the site was from a road and the kind of road it was. We even determined the site’s visibility, that is, how many other sites of the same period were visible from the highest point on the site.

We also entered into our computer the pottery finds, by date and by percentage of each kind of vessel; each sherd was described in detail. By giving quantitative values to each of these characteristics, we could “run” (that is, compare) the site with other sites and more objectively determine which characteristics changed from site to site and from period to period.d

To obtain all this information, we marched meter by meter under green olive groves, over white chalk cliffs and into the yellow desert plains of Manasseh.

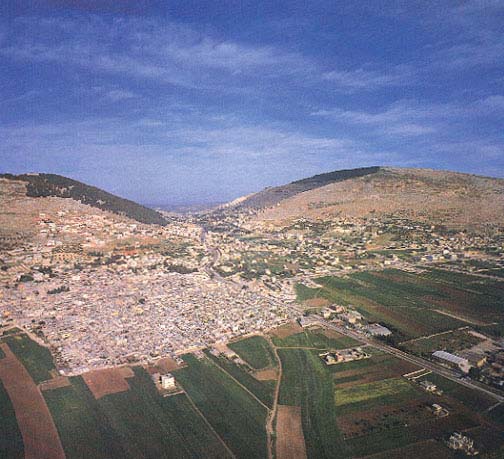

The territory allotted to the tribe of Manasseh in the western hill country of Canaan is approximately 800 square miles (2,000 square kilometers). Its eastern border is the Jordan River. On the west, its border is the coastal-plain highway sometimes known in Roman times as the “Via Maris” (the Way of the Sea). On the north, the border is the Jezreel Valley. Manasseh extends as far south as the city of Shechem.

Manasseh’s varied geological conditions include a wide range of hills on the west, desert fringe on the east and six fertile valleys that feed into the Shechem sincline.e Many roads cross it, the most important being the two branches of the Via Maris—the Dothan branch (mentioned in the Joseph story, Genesis 37:17–36) and the Nahal ‘Iron (ee-RON) branch. Manasseh also includes the richest water sources in the entire central hill country of Canaan.

Let us look at some results of our study.

From the Middle Bronze IIB period (1750–1550 B.C.E.), we found 116 sites. In the next archaeological period, the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.E.), there were only 39 sites. From Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.E.), the number climbed again to 136 sites.3 In short, the number of sites vastly declined in the Late Bronze Age and shot up again in Iron Age I, when, all agree, the Israelites arrived.

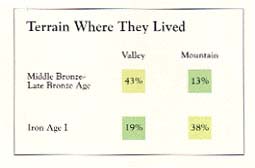

Our statistical analysis was able to establish that the Iron I settlers utilized the soil in a different way than the occupants of the land in the preceding period. We found that 43 percent of the Middle and Late Bronze period sites were concentrated near the valleys, with their rich, alluvial soil; however, only 19 percent of the Iron I settlements were found there. Conversely, only 13 percent of the MB–LB sites farmed the terrarossa (red mountainous) soil, but 38 percent of the Iron I settlements utilized this soil. (The balance of the settlements used other types of soil.)

The implication is clear. Something must have prevented the Iron I people from fully utilizing the fertile valleys, forcing them to depend instead on the less rich, terra-rossa soil farther up in the hills. The obstacle could have been a different population, which had prior ownership of the richer soil in the valleys—the Canaanites!

Despite this, we now believe that the Israelites must have lived in a kind of coexistence with the Canaanites. The Canaanites apparently allowed the Israelites to utilize some of the valleys, but this was limited. And the natural question arose: Why?

Botanical data help us to flesh out the story. The principal original growth in the valleys was a forest of Tabor oaks (Quercus ithaburensis). This beautiful tree creates parklike areas with wide spaces between the trees, especially suitable for grazing. In the hills above the valleys, the vegetation was primarily a maquis—wild, bushy land—of the Mediterranean type. Maquis is not nearly as suitable for grazing sheep and goats. The early Israelites probably grazed their flocks in some of the oak forests in the valleys, while engaging also in primitive, grain agriculture.

Let us again turn to our computer. We used 11 different computer codes to describe hill-country topography, such as an edge of a ridge, a margin of a valley, a high peak, a saddle, etc. From this information, we were able to determine that 53 percent of the Iron I sites were in hilly topography, but that only 15 percent of the MB–LB people dwelt in the hills. The valleys are much easier to settle than the mountains. This topographical analysis supported our conclusions regarding the relationship between the early Israelites and Canaanites. The Canaanites, as previous occupants, had most of the better sites in the valleys and owned the land there. The Israelites for the most part went higher up. However, about one-third of the Iron I people settled near the valleys. To understand this datum, we must consider the relative dates of the Israelite settlements. We will return to this factor later.

The Bible, at least implicitly, agrees with this picture of Israelite-Canaanite symbiosis. It does not record a single conflict between Israelites and Canaanites in the Shechem area and the northern hill country in the settlement period.f Most battles and wars in the Book of Joshua took place in southern or northern Canaan. The Biblical writers, however, did not explain why almost no conflict occurred in the northern hill country. Why did the Canaanites seem to cooperate with the Israelites, and vice versa? As we shall see, both sides had much to gain from their peaceful coexistence, while conditions were different in other regions.

The picture, as it has developed so far, is of a new group of people—Israelites—in the territory of Manasseh, having a new pattern of settlement—small villages, rather than fortified cities—and using natural resources in a different way than the previous inhabitants (Canaanites). It seems that the new group of Israelites coexisted with the Canaanites already settled there, at least during the first stage of the settlement. The newcomers settled partly in the valleys, especially in the beginning of the process, near and beside the Canaanites, but mostly they settled in the hills.

Water is of course critical in this relatively dry land. William F. Albright, whom I have already mentioned, believed that what enabled the Israelites to settle in the hills was the appearance of iron tools, with which they could dig water cisterns in the rock; according to this hypothesis, the Israelites could establish new villages in the hills by collecting rainwater in rock-hewn cisterns. This hypothesis gained wide currency, and for a long time it was considered authoritative. Since Albright proposed it in 1942, the position has not been seriously reexamined. When we tried to look at the question in light of our data, we observed that water cisterns were simply not found in the majority of the Iron I sites so far excavated. Although a few cisterns were carved in the soft, impermeable Sennonian chalk (as at Khirbet Raddanah), 90 percent of the Iron I sites are located on hard Cenomene-Turonian limestone, where plastering would be necessary to prevent water leakage. In these areas, no water cisterns were found. Albright’s hypothesis could no longer stand in light of the new data, and this ecological basis for the settlement in the hills must be altered.

How then did the early Israelites in the hill country supply themselves with water?

As has long been known, one of the most characteristic features of early Iron Age I settlements is the ubiquitous collared-rim pithos. This is a large storage jar that stands about 70 inches high and holds 10 to 15 gallons (40 to 60 liters) of liquid. It has a wide, short neck above a large body, and the shoulder is decorated with a ridge that gives the appearance of a little collar. Hence the name that archaeologists have given to it: the collared-rim jar, or collared-rim pithos. In excavated Iron I sites in the hill country, approximately 30 percent of the total pottery inventory consists of collared-rim storage jars. Moreover, the collared-rim pithos went out of use and disappeared after the period of the settlement and the Judges (Iron Age I).

Putting all this data together, I believe that the Israelites used the collared-rim pithos first and foremost to store water—it was the original Israelite cistern. During the United Monarchy (beginning in about 1000 B.C.E.), when iron tools became more common, water cisterns appear at all Israelite sites. Then the collared-rim pithos was no longer necessary, and it disappeared.

But still the Israelites had to get water to fill their jars. Where did they get it from? Again we turn to the computer.

The majority of the 39 Late Bronze sites, where the Canaanites dwelt in Manasseh during the 13th and 12th centuries B.C.E., were located near natural water sources, such as springs and rivers. The computer revealed a heavy dependency on perennial water by these Canaanites. They owned the water source and controlled it. Even today, it is common to find villages in the hill country that own their springs and sell the right to use the water to shepherds grazing their flocks in the area. The Bible poetically describes this connection between man and water source when Moses begs the Edomite king for permission to buy water if the Israelites would be permitted to pass through Edom on their way to Canaan (Numbers 20:14–19).

The implication for the early Israelites is clear: The Israelites had to cooperate with the Canaanites to get permission to graze their flocks and to bring water from Canaanite-owned springs, as much as six miles away, to their newly founded villages. The Israelites would fill their collared-rim pithoi and transport them on donkeys. Ethnologists could observe this same process in hill country villages as recently as 20 or 30 years ago, although the water-storage jars were not of the same collared-rim type.g

The only freely available water sources in the territory of Manasseh, and indeed in the central hill country generally, are the two rivers in the east, the Far’ah (far-AH) and the Malih (mah-LEEKH). They wend their way in all seasons of the year from the valleys on the eastern slopes to the Jordan River. Only at the Far’ah and the Malih could the incoming Israelites water their flocks by right, without hindrance. No one could control these rivers. In these river valleys we found approximately 25 new Iron I sites. There, and in the adjacent desert fringes, the Israelites could find enough grazing land for their flocks in the early stages of their settlement, during the period when shepherds were becoming farmers, or what scholars call the process of Israelite sedentarization.

But the next question that arises is this: Where did these new settlers come from? This question bitterly divides scholars studying Israelite origins. Some, like Mendenhall and Gottwald, claim that most if not all of the early Israelites were really Canaanites who defected from the Late Bronze Age urban centers in the west and the north of the hill country. Other scholars claim the Israelites came primarily from somewhere else, as the Bible says.

With the aid of computerized pottery sequences, we found that the Iron I sites with the earliest vessels were all concentrated along the Jordan Valley and the eastern rivers. Three key vessel-types—including cooking pots, bowls and decoration—were identified for this purpose. The idea that cooking pots are a valuable tool for dating the settlement process is not new. The cooking pot is basic to any household, so it is found in large quantities. Moreover, it changes form relatively fast. The rapid change of ethnic groups and populations in 13th-century Canaan left signs on the cooking pots of the period, because their form in the 13th century (Type A, similar to the Late Bronze “Canaanite” prototype) is different from 12th-century cooking pots (Type B, the “Israelite” type) and is even more different from 11th- or 10th-century cooking pots (Type C). So, by comparing the relative number of each type in an early Israelite site, one can establish the site’s place in the historical and archaeological sequence (see the sidebar “Using Pottery Forms and Width Stratigraphy to Trace Population Movements”). The second type of vessel used for dating is a special kind of bowl that we call “Manassite”; it appears in the 13th and 12th centuries and then disappears. Its presence or absence helps to establish whether the site is early or late.

We also have another chronological indicator—not the shape of the vessel but its decoration. The handles of some Iron I vessels have small indentations on them, made while the clay was still wet. But the frequency of these indentations varies according to area and time: They appear first and foremost in the 13th to 12th centuries B.C.E., mainly in eastern Manasseh.

With these tools in hand, we could try to trace the direction and the relative dates of the early Israelites in Manasseh.

From the results thus gained, a clear picture emerges. The earliest sites were founded in the 13th century (and partially in the 12th century) in the Jordan Valley and along the eastern rivers. We call this stage A. The next group of sites were founded in the 12th century in the eastern and inner valleys of Manasseh—at valleys such as Dothan, Tubas, Sanur, Zebabdeh and the environs of Shechem. We call this stage B. Only at the end of the 12th and in the 11th centuries were sites founded in the hills surrounding the valleys. We call this stage C.

Sites from each stage existed within their own economic and ecological context. In stage A, the settlers were seminomads in the process of sedentarization. During stage B, an economy based on wheat and barley farming began to develop, perhaps with the addition of some olive groves and vineyards. Stage C utilized mountain-terrace agriculture, so beautifully described in the Bible as the symbol of a prosperous, contented Israel (1 Kings 4:25 [5:5 in Hebrew]; 2 Kings 18:31; etc.).

This surprising new picture reflects a different process from what has been previously proposed. We now have archaeological evidence of movement from the east, which dovetails with the ecological evidence: Seminomads from the east entered the northern Jordan Valley, probably from Transjordan, grazing their flocks in the desert fringe and watering them in the streams.

In no other region of the land of Israel has such evidence been discerned so far—not in the Negev, nor the Galilee, nor the desert fringes of Ephraim and Judah, all of which are more-or-less archaeologically well known.

Instead of—or in addition to—the traditional Biblical picture of an entrance through Jericho, it now seems that the principal entry occurred in the northern part of the Jordan Valley, probably through the Damiyeh pass and elsewhere south of the Beth-Shean valley, opposite Shechem.

With this conclusion, evidence was found for a possible outside origin of the Israelites.

Let me digress, or at least appear to digress.

In 1917, Ernst Sellin, an often unappreciated and forgotten German pioneer in Biblical archaeology, published a booklet in German entitled Gilgal. Sellin was aware that some of the most important and earliest Israelite cultic traditions preserved in the Bible were concentrated in the area of Shechem and its environs. In no other place in Israel were three consecutive altars erected to Yahweh, the Israelite God. First by Abraham:

“When they arrived in the land of Canaan, Abram [his name was later changed to Abraham] passed through the land as far as the site of Shechem. … The Lord appeared to Abram and said, ‘I will give this land to your offspring.’ And he [Abram] built an altar there to the Lord [Yahweh]” (Genesis 12:6–7).

Then by Jacob:

“Jacob arrived safely in the city of Shechem [after his 20-year sojourn working for Laban] which is in the land of Canaan. … He set up an altar there, and called it El-elohe-yisrael [El, God of Israel]” (Genesis 33:18 Genesis 33:20).

Third, by Joshua: After the people were instructed by Moses to erect an altar to the Lord on Mt. Ebal (“as soon as you have crossed the Jordan into the land that the Lord your God is giving you” [Deuteronomy 27:2 Deuteronomy 27:4]), Joshua complied by building an altar (Joshua 8:30–31).

This last tradition, Sellin realized, openly contradicted the Jericho tradition, which has the Israelites entering the land much farther south, at Jericho: “Joshua, son of Nun, secretly sent two spies from Shittim, saying, ‘Go, reconnoiter the region of Jericho’” (Joshua 2:1). After a favorable report from the spies (Joshua 2:24), the Israelites crossed the Jordan River into Canaan. “The people crossed the Jordan near Jericho” (Joshua 3:16).

If the first thing the people were required to do after entering the Promised Land was to build an altar on Mt. Ebal—literally “in the same day” (Deuteronomy 27:2)—they must have crossed the Jordan somewhere near the present-day Damiyeh bridge in the north, opposite Shechem, not at Jericho.h

Sellin resolved the contradiction by supposing two entrance points. Without questioning the crossing at Jericho, Sellin concluded that Deuteronomy 27, which instructed the Israelites to build an altar on Mt. Ebal as soon as they crossed the Jordan, preserved a historical memoryi of a northern group of Israelite tribes who entered the land from Gilead and the valley of Succoth. Following Sellin, we believe that they were the carriers of the traditions concerning the Mt. Ebal altar in Deuteronomy 27 and Joshua 8. Professor Benjamin Mazar of the Hebrew University has further elaborated this idea. He identified the valley of Succoth at the point where the Jabbok River enters the Jordan—exactly opposite Wadi Far’ah—as a vital area in the patriarchal narratives and showed how this same area played a central role in early Israelite history.4

According to the Jericho tradition, however, the important site of Gilgal was in the neighborhood of Jericho: “The people came up from the Jordan … and encamped at Gilgal on the eastern border of Jericho” (Joshua 4:19), where Joshua set up 12 stones to commemorate the Jordan crossing.

Sellin knew, however, of another Gilgal, a northern Gilgal, a rival to the famous Gilgal of Jericho. (Hence, the title of Sellin’s book, Gilgal.) In Deuteronomy 11:30, after describing how the blessings should be pronounced on Mt. Gerizim and the curses on Mt. Ebal, the text locates these two well-known mountains in these words:

“Are they [Gerizim and Ebal] not on the other side [of the] Jordan, by the way where the sun goes down [west], in the land of the Canaanites that dwell in the country over against Gilgal, besides … Moreh.”

Apparently there were two Gilgals (and more), a northern one and a southern one (and others). It has long been recognized that “Gilgal” is not a specific location, but a type of fortified camp.

Sellin’s ideas did not attract much attention and were soon buried together with thousands of other such suggestions. I came back to Sellin’s book, however, as I tried to understand an unusual site discovered when we were surveying the southern side of the Wadi Far’ah, a major valley that leads from Shechem, Mt. Ebal and Tirzah to the Jordan River.

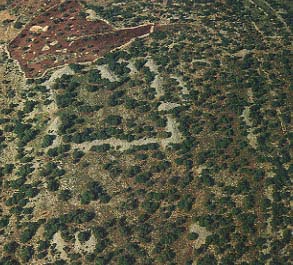

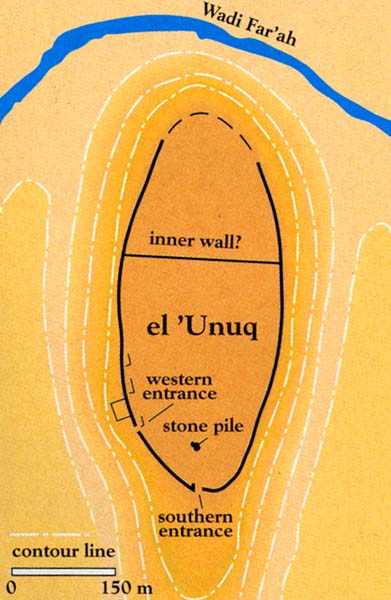

I vividly remember when we first saw this unusual site; it was a clear autumn day in 1985 when we came upon a large enclosure encircled by a wall nearly 6 feet wide. The enclosure is located on a long, oval hill. To the north, deep down, is the gorge of the Wadi Far’ah, surrounded by its 1,000-foot-high cliffs; to the east and west are steep slopes. Only on the south is the hill connected by a saddle to the surrounding area.

The oval enclosure measures approximately 800 feet in the longer direction and nearly 500 feet in the shorter direction. Its wall was built of unworked stones, similar to but slightly smaller than those found in the altar we had previously discovered on Mt. Ebal.j The Arabs call this enclosure el ’Unuq (OO-nook), the necklace, because of its shape. As with almost all of the discoveries in this area, we were apparently the first professional archaeologists to visit the site; not only was there no reference to it in the recent literature, but even the half-legendary explorers Claude Conder and Lord H. H. Kitchener did not mention it in their famous British survey of the 1870s.5

The enclosure of el ’Unuq is a large fortified camp, probably empty inside except for a dividing wall, some structures near the wall and an isolated stone pile. We could discern the main gate on the south side and an additional small opening on the west side. The inner wall subdivided the place into two unequal areas, two-thirds on the south and one-third on the north; the few simple stone structures are concentrated near the southwestern side. An especially interesting feature is the stone pile, located on the long axis of the southern part of the oval-shaped enclosure. What did this pile of stones cover? Without excavating it, no one can tell. Our guess is that it simply hid something of a special character. But it could be something else as well. (The excavation of the site is one of our principal future goals, once we find a source of funding, the lack of which being the main obstacle all along the way.)

Returning to the enclosure: It is probably not a village, town or settlement. It seems not to have had any permanent living quarters inside. It was not used for keeping sheep nor for other agricultural purposes; the fortification wall is much too monumental for that. Yet the fact that people somehow lived there was clear after we found considerable pottery. The earliest pottery repertoire dated to the 13th and 12th centuries B.C.E., nearly identical to the pottery found at the Mt. Ebal site (stratum 2) we had excavated earlier.6

It seems evident that this oval enclosure was some kind of a camp from the early Iron Age I period, that is, from the period of Israel’s earliest history in Canaan. But can we be more specific?

It has become fashionable in the last decade or so, especially among a group of scholars who regard themselves as “Syro-Palestinian” archaeologists,k to ignore and even to shun the Bible. The reasons for this inclination are various—from sociological to personal and political.

After years of archaeological research, however, I believe it is impossible to explore Israel’s origins without the Bible. At the same time, the research should be as objective as possible. The Bible should be used cautiously and critically. But again and again we have seen the historical value of the Bible. Again and again we have seen that an accurate memory has been preserved in its transmuted narratives, waiting to be unearthed and exposed by archaeological fieldwork and critical mind-work.

With these cautionary considerations in mind, we turned in our research to the Bible. In Deuteronomy 11:30 is the famous geographical guide to this area that I have already quoted. Moses is instructing the Israelites as to what they should do when they cross into the Promised Land. They are to pronounce the blessings on Mt. Gerizim and the curses on Mt. Ebal. Then the Biblical text locates these two mountains “over against Gilgal” (Deuteronomy 11:30).

This description refers to the west side of the Jordan. From the heights of Gilead, the sun sets in the west, beyond the pass through the Wadi Far’ah.

“Over against Gilgal.” Could this enclosure of el ’Unuq, only four miles from Mt. Ebal and Shechem, be the northern Gilgal referred to in this famous verse? I immediately thought of Sellin’s almost forgotten, but now seemingly prescient little book and its ideas.

Of course, we cannot be sure this enclosure is the northern Gilgal referred to in Deuteronomy 11:30, but there is no site with better credentials. Indeed, there is no other known candidate for this Gilgal at all!

This identification is buttressed by the etymology of Gilgal. In the opinion of most scholars, the Biblical Gilgal refers to a roundish, fortified site with cultic characteristics, a camp or a place where the people prepared for their campaigns.7 But we would like to do more than identify this site. It is part of a larger picture. It must be understood in conjunction with the altar we excavated on Mt. Ebal, and both must be understood in the larger context of our survey.

BAR readers will recall that the Mt. Ebal altar is a unique installation from the earliest days of the Israelite settlement in Canaan. It may well be the site related to the tradition that Moses instructed the people to erect an altar as soon as they entered the Promised Land in Deuteronomy 27:2–7, an instruction fulfilled by Joshua, as recorded in Joshua 8:30–35.

The date of the Mt. Ebal altar, established after eight seasons of excavation, was determined by the pottery as well as by two Egyptian scarabs from the last third of the reign of Ramesses II (1250–1220 B.C.E.).8

The design of the Mt. Ebal altar, according to our view, is the oldest prototype of the Israelite burnt-offering altar, which was present much later, in the Second Temple, and which was destroyed by the Romans in 70 C.E. The Second Temple altar is described in the Mishnah (a postdestruction Jewish legal tract), in the Temple Scroll from the Dead Sea Scrolls and in the works of the first-century Jewish historian Josephus. If the Mt. Ebal altar is indeed the prototype of this altar, it identifies, for the first time, a distinct ethnic group—the Israelites—whose sacred architecture continued with only minor changes from 1200 B.C.E. (the date of the Mt. Ebal altar) to 70 C.E. (the date of Roman destruction of the Second Temple altar). Thus, we can now legitimately claim that we are able to identify the material culture of the settlement sites that correlate with the Mt. Ebal altar in that early period: They are, at least in most cases, Israelite.l In short, we are now able to identify the Israelites archaeologically by the remains of their religion.

Six years ago in these pages, it was pointed out that the Mt. Ebal altar site conforms to the Biblical accounts in Deuteronomy 27 and Joshua 8—in location, date and character. Now the same thing can be suggested about the enclosure we have investigated on the south side of the Wadi Far’ah with respect to the reference in Deuteronomy 11:30 to a northern Gilgal. Can we take an additional step? Can we connect these discoveries to the process of the Israelite settlement?

In the first part of this article, it was suggested that the earliest Israelites moved slowly westwards from the Jordan Valley to the eastern valleys of Manasseh and then, farther to the west, to the hilly areas of Manasseh.

But what happened next? While many scholars have proposed different models for Israel’s emergence in Canaan—conquest, peaceful infiltration, peasant revolt or social revolution—few, if any, have attempted to trace the movement of the tribes once inside Canaan. The reason for this reticence is understandable: There simply was not enough material evidence to do this, apart from the highly confused Biblical material. Now the accumulated evidence—not only from our survey, but from other surveys and excavations as well—permits us to try tracing these footsteps.

In recent years it has become increasingly clear that the settlement of the tribes in the southern part of the hill country, the territory of Judah, was later than the settlement in the northern part of the hill country. In the territory of Judah, only about 20 Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.E.) sites have been discovered, compared with more than 200 sites in Manasseh and Ephraim together. The area of Manasseh and Ephraim totals 1,600 square miles (4,000 square kilometers) compared to about 800 square miles (2,000 square kilometers) in Judah, but still this fails to account for the tenfold difference between 200 sites versus 20 sites.

What this may indicate, according to our results, is that the initial Israelite settlers entered Canaan in the territory of Manasseh and gradually moved south, first to Ephraim and only later to Judah.

Further evidence for this conclusion comes from the traditions preserved in the Bible. First, we can follow the movement, according to Biblical tradition, of early Israelite cultic centers. The earliest cultic centers, as we have seen at Mt. Ebal, were located in the Shechem area,m in the territory of Manasseh. These cult centers later “moved” south to the territory of Ephraim when Shiloh inherited the position of the Shechem area with its altar on Mt. Ebal. Shiloh then became the national religious center. In Judges 9 we are told of Shechem’s destruction by Gideon’s son Abimelech, presumably about the mid-12th century B.C.E. Later the ark, attended by the priest Eli, and still later Samuel, was brought to Shiloh (1 Samuel 1–4). (It is interesting that, unlike the Shechem area where both Abraham and Jacob set up altars [Genesis 12:6–7, 33:20], Shiloh is not mentioned in the patriarchal narratives.) This dovetails with our archaeological evidence: The Mt. Ebal altar was abandoned in the mid-12th century.

According to the excavators of Shiloh, “the Israelite settlement at Shiloh began in the 12th century B.C.E.”n It was destroyed about a century later, approximately 1050 B.C.E. The “movement” from Mt. Ebal and Shechem to Shiloh represents the transition of Israel’s center of gravity from Manasseh to Ephraim. This transition seems to correspond to the gradual movement of the settlers southward. This southward movement continued until, at the end of the process, in about 1000 B.C.E., Jerusalem replaced Shiloh after the latter’s destruction by the Philistines. The move to Jerusalem, on the northern border of the tribe of Judah, was of course made possible by David’s capture of Jerusalem from the Jebusites (2 Samuel 5:6–10). David made Jerusalem his religious as well as political capital by moving the ark there (2 Samuel 6:12–23). By this act he also declared Judahite superiority.

In conclusion, the available data—archaeological and Biblical—indicate that the earliest massive Israelite settlements west of the Jordan were presumably in the territory of Manasseh and that they branched out from there, mostly to the south, but also to the north.

Two final notes:

First, the archaeological evidence summarized here is clearly inconsistent with the theory currently fashionable in some circles that Israel emerged out of Canaanite society, as a kind of peasant revolt or social revolution.o As our archaeological data shows, the Israelites came from outside Canaan, at least in Manasseh. They entered from the east,p occupying desert fringes alongside the already-settled Canaanites. They later moved into the hill country and adjacent valleys. There is no archaeological evidence for a movement from the great Canaanite cities north and west of the hill country toward the hill country in an eastward direction.

Second, what of the Biblical tradition of an entry into Canaan opposite Jericho? The archaeological evidence for this is meager. The archaeological evidence shows that Judah’s allotment was the last to be settled, not the earliest. There are relatively few Iron Age I settlements in Judah. We have no archaeological evidence of a movement from the Jordan Valley into Judah’s territory during Iron Age I. Moreover, Jericho probably did not exist in the 13th century, or if it did, it was a small village.q

A hundred years ago, the famous German scholar Julius Wellhausen claimed that the Jericho tradition was created as a result of a Judahite project to rewrite Israelite history.9 This rewriting was an attempt to discredit the principal role played by the northern tribes in Israelite history and to glorify the role of Judah and the house of David. Is that why the Jericho tradition is so emphasized in the Bible? Or perhaps, as Albrecht Alt claimed, the Jericho tradition is simply an etiological story, designed to explain the ruins of Jericho and Ai.10 Crucial though these questions are, they are difficult to answer on the basis of available evidence. Only further research can provide the answers.