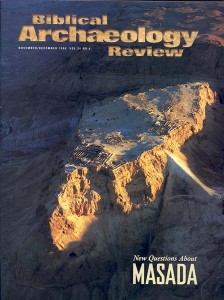

Masada—the very name resonates with images of bravery and freedom. In this imposing desert fortress, a greatly outnumbered band of fighters, unwilling to concede defeat during the First Jewish Revolt against Rome, held out for more than three years against a large imperial army after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. And when a successful Roman attack was imminent, their leader delivered a moving address, after which the assembled fighters chose to die by their own hands rather than surrender.

Or so the first-century A.D. historian Josephus tells us. In the 1960s, excavations led by Yigael Yadin, Israel’s most famous archaeologist, seemed to confirm key parts of Josephus’s account. Yadin even claimed to have found bones belonging to Masada’s defenders. But were they? In a fascinating excavation into decades-old records, Israeli archaeologist Joseph Zias suggests the bones were really those of Romans who lived here after the Jewish defeat. Sandwiched around Zias are articles by Nachman Ben-Yehuda and Ze’ev Meshel. Ben-Yehuda looks at a difficult passage in Josephus’s account of the Roman siege to pinpoint where the mass suicide occurred. You may not learn whether it occurred, a matter of scholarly dispute, but you’ll have a much better understanding of what the site was like at the time and where the suicide occurred if it occurred. Lastly, Meshel places Masada in a wider historical and geographical setting: The Judean Desert forts, like Masada, were often not just the refuge of rebels, but last-ditch administrative centers of governments-in-exile that had already lost urban centers like Jerusalem.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address.