Voices from Hazor

Sidebar to: Excavating Hazor, Part Two: Did the Israelites Destroy the Canaanite City?

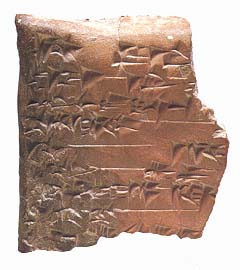

In the 1960s a youngster stumbled across a small piece of a broken tablet at Hazor. The cuneiform text impressed into the clay proved to be part of an ancient foreign language dictionary—translating terms from Akkadian, the diplomatic lingua franca of the eastern Mediterranean world in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, into Sumerian. The terms are economic: “rate of exchange,” “market rate,” “price.” Presumably, a learned scribe at Hazor created the dictionary to help his students or colleagues translate and write complex texts concerning trade. The discovery of the tablet suggests that the king of Hazor once had a school of scribes who helped with his foreign correspondence.

Until the discovery of this tablet, our evidence of writings from Hazor came from the correspondence found in the 18th-century B.C.E. royal archive of Mari, on the Euphrates, and the 14th-century B.C.E. archive of Pharaoh Akhenaten, discovered in Tell el-Amarna and called the Amarna letters. With the accidental discovery of this and one other tablet at Hazor, excavator Yigael Yadin became increasingly confident that he would unearth a royal archive in the site’s palace. “I will go back to Hazor,” Yigael Yadin told BAR just a year before his death, “and I think that I will find an archive there.”12

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address.