Paleography—An Uncertain Tool in Forgery Detection

Until recently, paleography—the study of the form and slant of the letters of an ancient inscription—was the chief means of determining whether an inscription was authentic or a modern forgery. The shape of each ancient letter has developed throughout history. Every 25 or 50 years, the way a letter is written changes slightly. To make things more complicated, the letters may be written in formal script or in cursive script or in semi-formal or semi-cursive. In this way, an expert paleographer can date an inscription. And if all the letters don’t cohere, it spells forgery. It was commonly thought that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to fool an expert paleographer. A forger would need to be an expert paleographer himself/herself and also be an expert engraver or penman to carve the letters into the stone or write them on a piece of pottery.

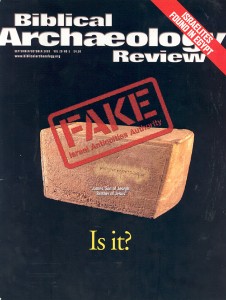

The BAR article announcing the James ossuary inscription—“James, the son of Joseph, the brother of Jesus”—was written by one of the world’s most distinguished paleographers, André Lemaire of the Sorbonne. He was confident of the paleography; the inscription was authentic.

Because of the extraordinary nature of the inscription, we nevertheless sought the opinion of other leading paleographers—Harvard’s Frank Cross; Kyle McCarter, the Albright Professor at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore; Ada Yardeni, an Israeli specialist who wrote The Book of Hebrew Script. We also consulted an Aramaic specialist, Father Joseph Fitzmyer of the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. None found anything suspicious about the paleography.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address.