Did God Have a Wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel

William G. Dever (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2005), xiv+344 pages, $25.00 (hardcover)

“Did God Have a Wife?” is a sexy title to sell a book, but it is also a pivotal question in the author’s treatment of folk religion in ancient Israel. By the end of the book, I was not convinced that YHWH, the God of Israel (often written Yahweha), had a wife. On the other hand, I am not sure that he did not have a wife at a certain earlier phase in his history. The archaeological as well as textual evidence is ambiguous, although I believe the scales tip toward a negative answer.

The author is a well-known American archaeologist, with a fluent pen, who writes a readable book, with bits of gossip here and there, sometimes winking knowingly at his audience. He begins his book as a teacher, with an air of ex cathedra self-appraisal. He grades colleagues, some of them his former students, for their studies in religion, archaeology, anthropology and feminist studies.

In his introduction he declares that “This is a book about ordinary people in ancient Israel and their everyday religious lives, not about the extraordinary few who wrote and edited the Hebrew Bible ... My concern in this book is popular religion, or, better, ‘folk religion’ in all its variety and vitality.” He defines the difference between establishment religion and folk religion (or religions, as he prefers) in such a way as to sever from the study of religion any speculations on the divine, that is, theology. He restricts himself to the study of the religious practice of ordinary people. But this severance is almost impossible; even ordinary people, unsophisticated though they may be, have their own speculations, however crude they might be, about God(s). Otherwise these ordinary people would not bother to practice their religion.

The author declares his intent “to demonstrate that a cult of Asherah did flourish in Ancient Israel.”

The goddess Asherah emerges mostly from 14th–12th-century B.C.E. texts found at the city of Ugarit, on the Mediterranean coast of Syria. The language of the texts is Ugaritic, a branch of West Semitic, the same linguistic family as Hebrew. Written in alphabetic cuneiform on clay tablets, these Ugaritic texts contain myths about the goddess Asherah in the Semitic pantheon. Asherah of the Sea, as she is called there, was the consort of the old god El, the head of the pantheon, and she was the “creator of the gods,” their mother.

There is a chronological gap of at least 400 years between the Ugaritic texts and the Bible, however. One cannot jump directly from Late Bronze urban Ugarit to Iron Age rural Israel.

The Bible, on the other hand, is almost the sole source for studying Asherah in ancient Israel, notwithstanding the few archaeological texts of c. 800 B.C.E. (to be discussed later).

A most important point, wholly missing from Dever’s book, is any consideration of the fact that Asherah is totally absent from the Phoenician inscriptions of the first millennium B.C.E.b There is not a single mention of Asherah in this corpus, not even as a theophoric component in Phoenician personal names. It seems as if Asherah evaporated, vanished—or never existed—in the Iron Age (the first millennium B.C.E.), the age of Biblical Israel, at least as far as the Phoenician corpus is concerned.

‘Asherah appears 40 times in the Hebrew Bible. However, as is widely known and as Dever recognizes, “Much of the time the term ‘ashe¯ra¯h [in the Bible] apparently refers [not to a goddess but] to a wooden pole, or even a living tree. According to the several verbs used, this object [‘asherah] should be cut down, chopped into pieces, and destroyed, probably by being burned. Thus, it is clear that the ‘ashe¯rîm (masculine plural for ‘asherah) were prohibited cult symbols associated with ‘Canaanite’ religious practices.” To the extent that this is true, the Biblical ‘asherah was not a goddess at all, but a cult symbol much like a standing stone.

Only in five cases in the Bible where ‘asherah is mentioned can there be any question. In all other Biblical references it is clear that ‘asherah is simply a wooden pole or a tree.

Because Asherah, the goddess, and ‘asherah, the wooden cult symbol, are written identically in Hebrew, which meaning is intended depends on the context. Let’s look at these five cases where the context is not absolutely clear.

In 1 Kings 15:13 the text speaks of the king’s mother who “made a miphles.et for the asherah.” The meaning of miphleṣet is ambiguous, but it is not “an abominable image made for Asherah,” as the translation used by Dever has it. Rather miphleṣet indicates that the asherah is something that makes one shudder or tremble (palaṣut, a shudder).1 This awful ‘asherah was made of wood, however, and King Asa cut it and burned it in the Kidron Valley near Jerusalem. It is by no means clear that the reference is to a statue of a goddess.

In 2 Kings 21:3, 7 we are told that King Manasseh “made an ‘asherah, like Ahab king of Israel,” and “he put the statue of the ‘asherah that he made” in the Temple. However, his grandson, King Josiah, “removed all the vessels made for the Baal and the Asherah and the Host of Heaven and burn[ed] them” in the Kidron Valley (2 Kings 23:4). So this asherah, too, was wooden—a goddess or a cult symbol?

The most problematic Biblical verse is 2 Kings 23:7: “And he [Josiah] tore down the houses [i.e., rooms] of the kedeshim [most probably cult servants; there is no justification for describing these servants as male-prostitutes, as the New Jewish Publication Society translation does] that were in the House of YHWH, where the women were weaving batim for the Asherah.” The meaning of batim here is unclear. It would normally mean houses. Did the women weave tents for the Asherah? Dever suggests emending batim (houses), to read badim (garments, cloth, textiles). This emendation not only contradicts the principle of text interpretation known as lectio difficilior (the difficult reading is the preferred one), but the plural badim (singular bad) is used only in Late Biblical Hebrew. So Dever’s suggested emendation must be rejected.

What about the “450 prophets of the Baal and 400 prophets of Asherah who eat at Jezebel’s table” in 1 Kings 18:19? The story of Elijah and the prophets of Ba’al continues in the Hebrew text, but the prophets of Asherah are not mentioned again. True, they are mentioned in the text in the Septuagint, the early Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. On the other hand, they are not mentioned in 1 Kings 18:40, where only the prophets of Baal, but not the prophets of Asherah, are slaughtered by the people. Long ago the well-known Biblical scholar Julius Wellhausen proposed that “and the 400 prophets of the Asherah” in 1 Kings 18:19 was a later interpolation into the text.

Last, it has sometimes been suggested that Jezebel, the Tyrian wife of Ahab, brought with her into Israelite society the cult of Asherah. But, curiously enough, as I noted earlier, Asherah is never mentioned in the many Phoenician surviving inscriptions of the first millennium B.C.E.

In any event, the overwhelming references to the ‘asherah/Asherah in the Bible, are not to a deity, but to an artifact, most probably a wooden pole or a tree.

If ‘asherah were a goddess, we would expect her to have a temple, or at least an altar. But the Biblical texts never mention a temple or an altar for the ‘asherah. It never has its own temple or its own altar; it is always part of the paraphernalia of an altar. Thus, in the story of Gideon, the Lord orders Gideon to “pull down the altar of the Baal which belongs to your father, and cut down the ‘asherah which is beside it” (Judges 6:25). Elsewhere the Israelites are similarly commanded to obliterate the Canaanite altars and their paraphernalia: standing stones (maṣṣevot; singular, maṣṣevah) and sacred trees/pillars (‘asherot; plural of ‘asherah) (see Exodus 34:13; Deuteronomy 7:5; 12:3, etc.). Erecting maṣṣevot and ‘asherot beside altars to YHWH was often the custom in ancient Israel, as we learn from its Deuteronomistic prohibition: “You shall not plant/set up an ‘asherah, any kind of tree, beside the altar of YHWH your God that you make. And you shall not erect a maṣṣevah, such as YHWH your God detests” (Deuteronomy 16:21–22).

Now let us turn to the archaeologically recovered ancient inscriptions on which Dever relies, found at Khirbet el-Qom (Biblical Makkedah) in the Judean Shephelah (low hill country) and at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud in the northern Sinai.

At these sites, the name Asherah/‘asherah is mentioned in blessing formulae. At Makkedah the inscription reads: “Blessed is Uriyahu to YHWH and his Asherah/‘asherah.” At Kuntillet ‘Ajrud two inscriptions read: “I bless you (plural) to YHWH of Samaria and his Asherah/‘asherah” and “I bless you (singular) to YHWH of Teman and his Asherah/‘asherah.”

These inscriptions never mention Asherah/‘asherah alone. Asherah/‘asherah is mentioned only in connection with YHWH. True, it can be argued, as Dever does, that Asherah here is the consort of YHWH, but one cannot dismiss the argument that it was his sacred tree/pole. The epigraphic evidence is ambiguous.

Dever also relies on some crude drawings of figures that appear on the pithoi (large storage jars), on which the inscriptions from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud are written. He speculates that one of these figures is the feminine consort of YHWH referred to as Asherah in the inscription. But Dever should have known that the late Pirhia Beck (whom he quotes) has demonstrated that these crude drawings—which include Bes, a distorted Egyptian dwarf god—has nothing to do with the elegant calligraphic inscriptions. The drawings were overwritten on the inscriptions, with no regard to the texts!

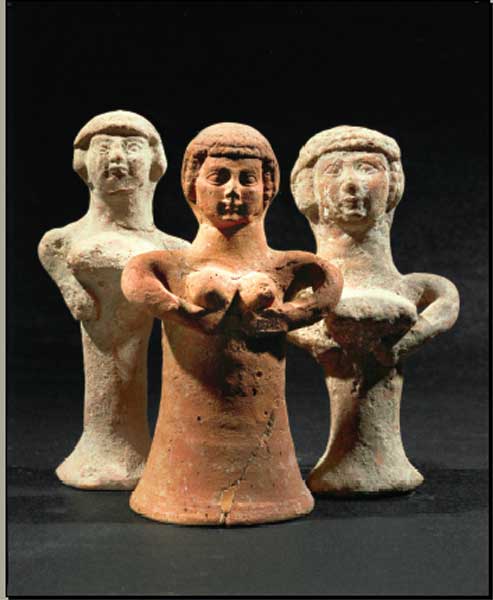

Dever also relies on non-inscriptional archaeological evidence for his contention that YHWH had a wife—the hundreds of figurines found in Judah from the end of the eighth century B.C.E. to the early sixth century B.C.E.. Dever contends that these figurines represent Asherah, consort of YHWH. Archaeologists commonly call these figurines “pillar figurines” because the lower part of the body is pillar-like (and hollow). The upper part is a woman supporting her large breasts. Dever insists they are Asherah: “These figurines clearly represent ‘Asherah’ (not ‘Astarte’), the principal Israelite female deity and patroness of mothers.”

If these figurines really represent a goddess (which I doubt), it is surely not the extinct Asherah, but the famous Astarte who was popular at this time in Phoenicia; her name runs through the Bible as the consort of Baal. Most of the Biblical references pair Baal and Astarte, as in the Akkadian ilani u ishtarti, “gods and goddesses.”

But I very much doubt that these figurines represent a goddess at all. Dever quotes University of Judaism scholar Ziony Zevit who refers to these figurines as “prayers in clay.” Zevit’s description of these figurines is right! They were used by women who prayed for lactation; hence the large breasts. It is not unlike some religious pilgrims today who, for example, leave a replica of a foot at a holy site as a prayer to heal an ailing foot.

Dever is unfortunately unreliable concerning any textual material. He does not read Hebrew or any other ancient language. Moreover, he makes a fool of himself when he discusses the Bible. A few examples (of many):

Dever writes: “That Isaiah was a patrician is also indicated by his status as an aristocratic advisor, almost a Prime Minister, under kings like Ahaz and Hezekiah.” Only God knows where Dever finds a hint to the effect that Isaiah served as a prime minister. Isaiah never acted as an advisor or a prime minister; he was a prophet. He was asked to pray for Hezekiah and for the delivery of Jerusalem, not to serve as prime minister.

Dever writes: “Hoshea, the last king of ... Israel ... [before the Assyrian destruction in the eighth century B.C.E.] is blamed for the catastrophe because he ‘set up pillars and Asherahs on every high hill and under every green tree, and there burned incense on all the high places (bāmôt)’” (2 Kings 17:10–11). It is not Hoshea who is blamed, Professor Dever, but Israel. The text reads “they” not “he.”

Dever quotes 1 Kings 16:32 as referring to the Temple in Jerusalem, but the Biblical text actually refers to the Baal temple that Ahab built in Samaria.

Dever writes that Passover “was to be celebrated at the full moon on the tenth day of the first month in spring.” Impossible, the full moon is always the 15th day of the month!

These examples could be multiplied—from Egyptian texts and late Jewish texts, as well as Biblical texts. Dever notes with approval the remark of a colleague that “the Hebrew Bible is ‘mute’ if you do not know Hebrew.” Back to school, professor!