Emmaus: Where Christ Appeared

Many sites vie for the honor, but Emmaus-Nicopolis is the leading contender

AT DAWN THE TOMB OF JESUS WAS FOUND EMPTY. Later that very day two of the disciples, Cleopas and another unnamed, were walking on the road to Emmaus when Jesus appeared to them, but they did not recognize him. As they drew near Emmaus, Jesus went to go on, but they pressed him to stay with them, saying, “It is toward evening and the day is now far spent.” At dinner, Jesus blessed the bread and gave it to them and “their eyes were opened and they recognized him.” All this occurred at a place called Emmaus. That same hour they returned to Jerusalem, where they told the others what had happened. And he appeared to them again! Jesus ate some fish that they gave to him, showing that he had been resurrected bodily. Then he led them out to Bethany on the Mount of Olives, where he blessed them and “was carried up into heaven” (see Luke 24:13–53).

This episode from the Gospel of Luke contains the only mention of Emmaus in the entire New Testament. But Jesus’ appearance to his disciples on the road to Emmaus and at dinner is one of only five post-Resurrection appearances recorded in the Gospels.

Where Emmaus was located has been a matter of considerable scholarly controversy. There are at least nine candidates. Only four, however, are serious contenders. Each has three main components that contribute to its possible identification as Emmaus: a spring [Emmaus means “warm well”], a distance of at least 60 stadia (almost 7 miles) from Jerusalem, and a location along a major ancient road. Each also has its problems. How do we decide which one (if any) is the New Testament Emmaus?

Emmaus, or Emmaus-Nicopolis, is the leading contender. Another possibility is Emmaus-Qubeibeh, northwest of Jerusalem (see Another Contender for the Honor: Emmaus-Qubeibeh); an old Roman fort near this site was named Castellum Emmaus in the Crusader period. A third contender is Abu Ghosh, just outside of Jerusalem. A spring there may have led some Crusaders to identify it as Emmaus; they built the castle Fontenoide and a church there in 1141. The fourth candidate is Qaloniyeh (ancient Colonia; modern Motza). The Latin for Motza could be Amassa; the Greek form, Ammaous, mentioned by the turn-of-the-era Jewish historian Josephus, is obviously similar to Emmaus.1

The problem with these last three suggestions is that none of them is attested as Emmaus earlier than the Crusader period.

But the first site mentioned, Emmaus-Nicopolis, has its problems too. It is, by the shortest route, about 17 miles from Jerusalem. According to the Gospel of Luke, the disciples “walked” from Jerusalem to Emmaus, ate a meal and then went back to Jerusalem, apparently all in the same day. Is that plausible?

Another problem for Emmaus-Nicopolis concerns the New Testament text. If you look at the Lucan text in your favorite translation, at the first mention of Emmaus it probably says that the village is 7 miles from Jerusalem, or 60 stadia in the Greek text from which the translation is taken. If 60 stadia is about 7 miles (as it is; a Roman stadium is 607 English feet), then a site at least 17 miles from Jerusalem does not appear to qualify. It’s much too far.

So there are two problems with identifying Emmaus-Nicopolis as New Testament Emmaus: First, the disciples would have had to walk about 35 miles in one day. Second, Luke says Emmaus is only 7 miles (60 stadia) from Jerusalem.

Consider the second question first: True, if you look at your Bible you will probably find that Luke says Emmaus is 7 miles from Jerusalem. But look at Luke 24:13 in the New Revised Standard Version; there you will find a footnote that says that “other ancient authorities read 160 stadia.” That figure (approximately 18 miles) fits quite nicely with Emmaus-Nicopolis.

There is plenty of evidence to support both sides of this textual argument— 60 versus 160 stadia. The often-authoritative fourth-century Codex Sinaiticus says 160 stadia. On the other hand, the other two of the great trio of ancient Greek Bibles, Codex Vaticanus and Codex Alexandrinus, both say 60. And each side can assemble a long list of other manuscripts favoring it, although the list containing 60 stadia is longer. On the other hand, Eusebius (third–fourth-century author of the famous Onomasticon), Jerome (fourth-century church father and translator of the Bible and the Onomasticon into Latin), Origen (third-century church father) and Sozomen (fifth-century church historian) all opt for 160 stadia as the correct Lucan text, thus supporting Emmaus-Nicopolis as the best candidate for New Testament Emmaus. Emmaus-Nicopolis is assumed to be the site of the Lucan Emmaus by almost all Christian pilgrim texts from the fourth century onward.

Modern scholars are just as divided as the ancient sources. According to Eerdman’s Dictionary of the Bible, “None [of the leading candidates for Biblical Emmaus] has won widespread approval.” The Anchor Bible Dictionary says 60 stadia is “the better reading.” The Editorial Committee of the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament calls the reading of 160 stadia a “scribal blunder,” the result of patristic efforts to confirm the site of Nicopolis as Biblical Emmaus. On the other hand, three prominent Israeli scholars in their recent Tabula Imperii Romani Judaea-Palaestina tell us that New Testament Emmaus is “probably Emmaus-Nicopolis.”2

What about the first problem? Is it reasonable to think that the disciples could walk more than 35 miles in a day? Here again, scholars are divided: The distance makes the reading of 160 stadia, according to the Anchor Bible Dictionary, “surely wrong”; people could not walk 35 miles in a day. On the other hand, “Anyone familiar with Palestinian Bedouin or Arabs in a pre-automotive culture would not doubt the disciples’ ability to walk forty miles in a day,” says the HarperCollins Bible Dictionary.

Someone recently identified another problem: The disciples arrived at Emmaus when it was “toward evening and the day ... far spent” (Luke 24:29). Would the disciples have eaten and then departed for Jerusalem after dark? No. In the orient, evening begins at 12 o’clock noon, when the sun begins to go down. They would have left in the early afternoon. Once they had finished their meal, they would have departed immediately to spread the good news. Moreover, although the text does not specify this, it is possible that they took a donkey or even ran part of the way out of sheer excitement in order to complete their trip to Jerusalem as quickly as possible and tell the other disciples of the appearance of the risen Lord.

In modern times Emmaus-Nicopolis was identified as New Testament Emmaus by the American Orientalist Edward Robinson when he canvassed the Holy Land in the mid-19th century. Robinson identified hundreds of Biblical sites, often on the basis of the survival of the Biblical name in current Arabic names. For example, the Arabic place-name Seilun identified Shiloh; Beitun identified Bethel; and Amwas (‘Imwas), the Arab village at the site of Emmaus-Nicopolis, identified Emmaus. It occupies a strategic position near Latrun, on the ancient road from the coast up to Jerusalem.

South of the village, Robinson also found the remains of an old church constructed of long, well-cut stones, with a semi-circular apse still standing at the end. In 1879 a French architect named Joseph Guillemot conducted the first archaeological excavation at the site and found, in the north apse of what was originally a triapsidal church, a pseudo-Ionic capital inscribed on one side, “One God,” and on the other, “Blessed be his name forever” (cf. Psalm 72:19). The first side is in Greek, the other side in what was thought to be Hebrew but is now identified by Israeli scholar Leah di Segni as Samaritan. At first the two inscriptions seemed to be from two different eras, but it is more likely that the capital dates to the fifth or sixth century A.D. The first side of the inscription (“God is one”) may be, the current excavators suggest, an echo of Deuteronomy 6:4: “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one.” The second inscription testifies to the presence of Samaritans (as well as Jews, Christians and Romans) in Emmaus. In any event, as subsequent Christian finds seem to make clear, the locals identified the site early on as the place of Jesus’ post-Resurrection appearance.3

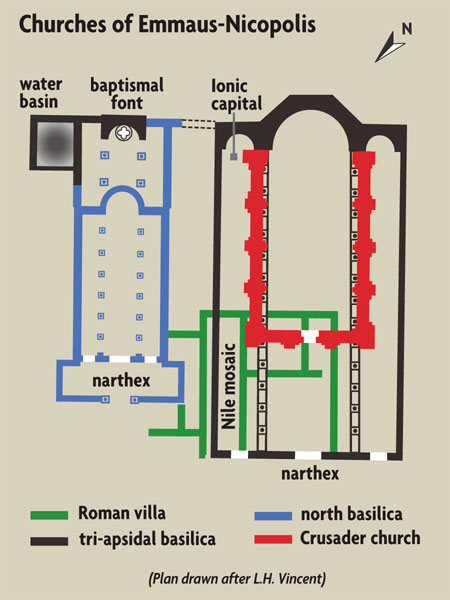

Between 1924 and 1930, Louis-Hugues Vincent, a prominent Dominican priest at the École Biblique et Archéologique Française in Jerusalem, excavated this church. In one corner of the nave, he found what he regarded as the remains of an earlier domestic structure that he dated to the Roman period. It was built of Herodian ashlars, and even earlier Hasmonean coins were found there. Perhaps the church was purposely built atop this house because it was thought to be “Cleopas’s House,” where the disciples recognized the resurrected Jesus. Perhaps this belief occasioned the construction of the church above the house. The new excavation team thinks the site may have been a domus ecclesia, a place of Christian worship before Constantine’s time (early fourth century). They also suggest that a fourth-century Byzantine chapel may have been erected on the site prior to the subsequent building of the triapsidal basilical church in the fifth century.

North of the church— and associated with it— Vincent identified an impressive structure as a baptistery.5 Within the baptistery is a beautiful trefoil baptismal font, one of the best-preserved baptismal fonts in the Holy Land. The baptistery building was supported by four columns. One of the column bases of the baptistery is still in situ. During this early period, only at bishopric seats were baptisteries in separate structures. This architectural feature is another indication of the city’s importance to Byzantine Christians.

In front of the baptistery, Father Vincent also excavated another church, which lies just north of the remains of the triapsidal church. Within the triapsidal church, he also explored a third church, which he attributed to the Crusader period (12th century). Although the precise dates for these structures are disputed, it appears clear that, at a very early period, the site was thought to be Emmaus of the New Testament and became an important center of Christian worship and pilgrimage. It is uncertain whether the site’s Christian importance resulted from its association with New Testament Emmaus or, on the other hand, a manufactured association led to the site’s Christian importance. This remains a question that can never be answered definitively.

More than 25 years ago, the current director of German archaeological work in the Holy Land, Karl-Heinz Fleckenstein, and his wife, Louisa, were guiding tours of Christian sites and became fascinated with Emmaus-Nicopolis. At that time, the site was abandoned and neglected. The Fleckensteins decided to try to mount an archaeological expedition to uncover new evidence for the correct identification of the site and the dates of many of its structures. The excavation, which finally began in 1993 and continued until 2005, was sponsored by a consortium of institutions including the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum in Jerusalem, represented by the well-known scholar Father Michele Piccirillo. The Fleckensteins and archaeologist Mikko Louhivuori served as principal investigators. Since 2005 the excavators have been studying the finds and preparing an excavation report, but they also hope to return to the field.

The Fleckensteins believe that the site was identified as New Testament Emmaus as early as the third century. Of course, the later a contending site was identified as Emmaus, the less likely it is to be Emmaus of the New Testament. The oldest identification of Emmaus-Nicopolis does seem to go back much further than that of any of the other contenders.

In 130 A.D. an earthquake destroyed much of the site. For nearly a century thereafter, it was little more than a small village. One of the villagers, however, became prominent and influential: Sextus Julius Africanus was a Christian historian, traveler and Roman prefect. Africanus wrote a five-volume history of the world from the Creation to 221 A.D. (the Chronografiai). The well-known Church father Origen called Africanus his “brother in God through Jesus Christ.” In 222 Africanus led a delegation to Rome to seek the designation of polis for his city. The petition was granted by the emperor Elagabalus, and the city was named Emmaus-Nicopolis, the “victorious city of Emmaus.” As Emmaus-Nicopolis, the city began to thrive once again.

One never knows what one will find in an archaeological excavation. That is part of what makes it so exciting— and mysterious. Certainly one of the most unexpected finds at Emmaus was an Egyptian scarab of the Hyksos type. It depicts a masculine figure wearing a tall, cylindrical head cover. His hands are in the position of a “fighting god” with clenched fists. Under his left fist is a uraeus (serpent), the symbol of ancient Egyptian kings.6 The scarab dates to about 1800 B.C. What in the world was it doing at Emmaus? It was found near a Roman grave and may have been a talisman passed down through the generations. Or perhaps there was an Egyptian city here in the Middle Bronze Age, a city that still lies buried deep underground, awaiting discovery by another team of archaeologists. A grave from this period is said to have been found in nearby Neve Shalom. In the meantime, Middle Bronze specialists must now consider the significance of an Egyptian scarab found at Emmaus-Nicopolis.7

Most of the archaeological evidence uncovered here, however, comes from the Byzantine period but includes evidence from Hellenistic and Roman periods as well.

Jews, Samaritans, Romans and, later, Christians all lived here in what must have been a major town.

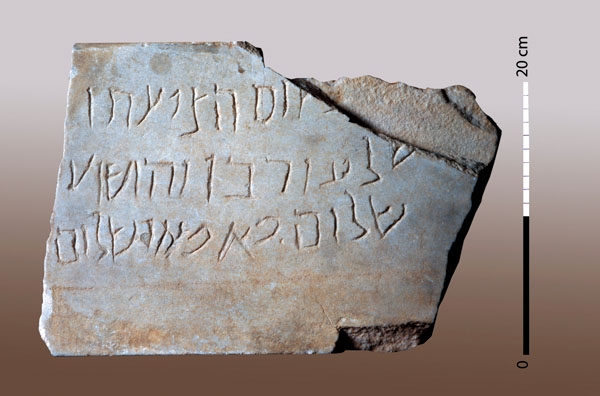

In the city museum of Jaffa, just south of Tel Aviv, is a fragmentary inscription from a Jewish tombstone that reads in Hebrew: “This is the resting place of Eleazar, son of Yehoshua. Peace from Emmaus. Peace.” According to Shimshon Seder, director of the museum, the tombstone was found in Abu Kabir (between Tel Aviv and Jaffa), about 17 miles from Emmaus-Nicopolis, and dates to the Roman-Byzantine era. Apparently this Eleazar hailed from Emmaus, most likely Emmaus-Nicopolis, which is closer to the find-spot than any of the other contenders. Eleazar was doubtless proud of coming from such an important town, and it was the custom at the time to indicate one’s hometown in an epitaph. This inscription is further evidence of the probable early identification of the site as New Testament Emmaus and is important for the epigraphic evidence of Emmaus written in Hebrew script.8

By the Byzantine period, the evidence suggests that Emmaus had become a fully Christian city. In 1894 a shattered stone plaque was discovered on a ridge to the west, overlooking Emmaus. The plaque, which cannot date epigraphically before the fourth century A.D., is now in the museum of the White Fathers adjacent to the Church of St. Anne in Jerusalem and reads in Greek: “In the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, beautiful is the city of the Christians.”

Since this inscription was found overlooking Emmaus, it is likely that it came from there. It may have stood over the portal of a church.9

The remains of the fifth-century Byzantine basilica (the south church) were overbuilt by the Crusader church, which still dominates the site. In the narthex area of the basilica (in front of the nave), the excavation team uncovered a graceful sixth-century A.D. mosaic featuring a chalice overflowing with water from which two birds are drinking. It is not difficult to imagine a variety of symbolic interpretations. The mosaic also includes fragments of fish, a bull, the head of a lamb, and other animals. In the middle is an inscription reading Kyrie Eleison (“Lord, Have Mercy”) and the genitive (possessive) form of the name Titus.

Beneath a mosaic in the south church, the excavators found a line of eight skeletons, all facing east toward the rising sun (as do churches from this period), with their arms crossed over their chests in Christian penitence, perhaps representing the cross. A radiocarbon test performed by the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot, Israel, indicates that the bones date somewhere between 260 and 420 A.D. They are probably the bones of monks who served in the church and who were buried without grave goods.

Another mosaic, found in the nave of the south church (where Vincent identified the Roman house), resembles the “Nile” scenes popular in the Byzantine period. In one panel a leopard attacks a gazelle; in another a lion takes down his prey. These representations of the danger of the wild contrast with nearby scenes of birds nestled peacefully in papyrus plants. These contradictory images are a common motif used by early Christian artists, sometimes said to symbolize the fight between Good and Evil. In his interpretation, Dr. Fleckenstein sees a reflection of the glorious appearance of the risen Jesus to his disciples in Emmaus after the “bloody and cruel events on Golgatha.”10

The excavators have uncovered a wide range of Christian artifacts, unfortunately often of uncertain date but mainly of the Byzantine period. For example, one of the hundreds of clay oil lamps from the Byzantine period (fourth–seventh centuries) is inscribed: “May the light of Christ shine on everyone” (cf. John 1:9). Others were decorated with depictions of ladders that perhaps symbolize the steps down into a baptismal font. These lamps are probably to be associated with the baptistery mentioned earlier.

The site is peppered with tombs of various kinds from many different periods. A number of them have recently been excavated.

One of the tombs revealed clear evidence of a Jewish presence in Jesus’ time: four ossuaries. Limestone bone boxes called ossuaries were used by Jews for secondary burial of bones, only from about 20 B.C. to 70 A.D. Thousands of ossuaries have been found in the Jerusalem area. The deceased was initially laid to rest on a stone bench in a cave or in a long rock cavity called a koch in Hebrew (plural, kochim) and a loculus in English (plural, loculi). About a year later, after the flesh had desiccated and fallen away, the bones were placed in an ossuary. Near the burial cave with these ossuaries were two rolling stones, presumably used to close tombs, much like those that must have closed Jesus’ tomb in Jerusalem. But these were only partially cut. Parts of the stones were still attached to the bedrock, as if the stone cutter had stopped for the day, intending to return to work in the morning.

Of the thousands of coins the excavators recovered, one is especially interesting: a coin of Valerius Gratus (15–26 A.D.). He was the Roman procurator who preceded Pontius Pilate. Gratus restructured the Temple governance in Jerusalem and appointed first Annas and then Caiaphas as High Priests.

We have emphasized the Christian connections with Emmaus. But, in addition to Jews and Samaritans, the city boasted an important Roman population. Indeed, probably the most elegant structure in the ancient city was a Roman villa that was found northwest of the basilicas and is being excavated by the current team. This villa had a mosaic floor and what appears to be the remains of a dye industry. Three basins carved into the rock permitted the passage of liquids from one basin to the other. A coin from the reign of Emperor Elagabalus (218–222 A.D.) was found, providing a probable date for the structure. As for the occupants, only a comb was found that might be connected to the lady of the house.

The continuing excavation of the site promises to shed new light on the intriguing history of Emmaus-Nicopolis.

Kathleen E. Miller provided research, reporting and translation of the German for this article.