Queen of the Philistines

BAR Interviews Trude Dothan

Trude Dothan is professor of archaeology at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and a pioneer of Israeli archaeology. She is a world-renowned expert on the Philistines and has excavated a number of their sites, including the major long-term excavation of Tel Miqne (Biblical Ekron). She recently spoke with BAR editor Hershel Shanks about her longtime fascination with the Philistines, as well as the many changes she’s observed in Biblical archaeology during the past 35 years.

Hershel Shanks: Can you believe it, Trude? BAR is 35 years old. How has the field changed in the past 35 years?

Trude Dothan: I don’t know whether it has changed. Maybe the people have changed. What we are doing a lot now—maybe this is after coming back from the dig at Gath, but all of us do it—the sciences are part of what we are doing. This will be a vital part of a dig.

How has the position of women in archaeology changed in the past 35 years?

You know, I was a full professor at Hebrew University. I can’t complain. It’s a big issue, not only in archaeology. There were always women in archaeology—for example, Kathleen Kenyon. When students come to me and ask, “How did you do it? How did you have a family and a home?” I say, well, my husband, Moshe, helped me. It always takes longer [as a woman]. That’s all. You work at home, you work at night.

Did you never feel any prejudice against you because you’re a woman?

No.

No disadvantage?

No, I don’t think so. Look, there is a problem. If a woman becomes pregnant, she cannot work. When I worked with [Yigael] Yadin, for example, my older son was born. He was here in the crib, and I had to go and feed him. We were sitting here discussing Hazor, and writing up the reports, and the bathroom was full of diapers. Yadin didn’t care. We would sit together, and just work. Danny would be crying sometimes. It depends on how you take it, whether you’re open to it. I won’t say it’s easy. I just say one thing: Don’t stop. If you do it and you enjoy it—if you have children, it’s not so easy—but just continue. Don’t stop.

What is it like to be married to another archaeologist?

Very good. Of course, it depends on who it is.

Who was the greatest archaeologist you have known?

[William Foxwell] Albright. He did wonderful things. We went to visit him at Johns Hopkins, and he took us for lunch at the Faculty Club. It was one of the first times I was out of Israel. We sat down, the three of us, Moshe and Albright and me. After a few minutes, somebody came up and whispered something to Albright. And he said, “Trude, I’m very sorry. Women are not allowed here.” I’ll never forget that. He was furious. He said, “I’m ashamed.” He took my hand, and we walked out and we sat in a nearby lounge.

What led you to archaeology?

I grew up in Jerusalem. My father was an architect. He came [to Palestine] from Vienna in the 1920s and he had many friends who were archaeologists. He came here because they asked him to come here to restore old buildings. And I used to go with him. I was only a small girl, but I liked it and I said, “I’m going to be an archaeologist,” not knowing exactly what it was. But I liked the excitement of it, the mystery of it, the adventure of it. I wanted to be an archaeologist, not even knowing in the beginning exactly what it was. I was lucky that I was in Jerusalem and had around me people who really understood it. My parents said, “You know, we don’t have money. You don’t get rich in archaeology.” But they couldn’t change my mind. I remember I went to [E.L.] Sukenik [Yadin’s father and one of the first archaeologists]. At that time he lived near us. At that time it was all little Jerusalem. Sukenik said, “Yes, you can be, but you know, you’re a woman.” But at that time Ruth Amiran was already in the field. I went to a few people, and they all thought this was not a great idea. But then I went to study with [Benjamin] Mazar, who really decided me. And also Moshe Stekelis, who was a prehistorian, and Professor [L.A.] Mayer, who was a specialist in Islamic art. I liked that because there was lots of art in his classes. So on the whole, there was just no question about it. I was going to do archaeology. But it was really Professor Mazar, who was not really a field archaeologist, who helped me. He was very clever in the way he understood people. He really knew what their strength was and how, in a way, to do it.

How did you get involved with the Philistines?

Through Tell Qasile. I was still a soldier. I was in the army.

That was Benjamin Mazar’s dig [in 1948]?

Yes.

Then later [his nephew] Ami Mazar dug there?

Yes, many years later [from 1974 to 1978]. Ami found a Philistine temple there.

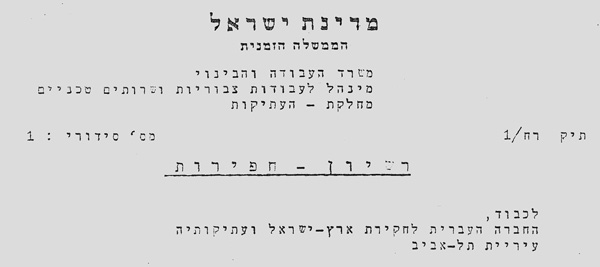

I was a student of Benjamin Mazar’s, and it was during the very first year of the state [of Israel]. We had Permit No. 1 of the new Department of Antiquities [see photo at right]. A few years ago at Tell Qasile, there was a small exhibit on the history of the site, and there they had Permit No. 1 on display.

Qasile was the first Philistine site that was discovered that is not mentioned in the Bible.

That’s true.

How did you know it was Philistine?

You have a good question there. It was recognized at the time, whether wrong or right. The finds showed they came from the west. I was fascinated by the idea. What really interests me is the interconnection of the Philistines with the west, with the Aegean world. And I’m also especially interested in art. So this combination led me to my interest in the Philistines.

Why are you especially interested in art?

My mother was a painter. My father was an architect, as I said, and also an artist. Leopold Krakauer and Grete Wolf Krakauer.

After all these years, how do you feel about the Philistines? Do you have a personal relationship with them?

I am most interested in where the Philistines and other Sea Peoples came from. That’s why I went to Cyprus to dig. How do you understand something like the movement of the Philistines [to the east]? Around 1200 B.C. something happens. It was a period of catastrophes. What was it? We don’t know. This is now one of those hot subjects, trying to find out why civilizations collapsed. What happened in about 1200 B.C.? There was the end of writing, the end of language. Ugarit [on the Syrian coast] and places like that were suddenly abandoned. And it happened not only there. This is one of those general questions: How to understand it? People like the Philistines left their homelands. They came from the Aegean world. They were not traders. They were people who remembered the homes from which they came. They brought their memories with them. They wanted to live in their new home in the milieu they were accustomed to.

Why did they leave?

The explanation used to be all kinds of wars. Now the trend is to explain it as a result of some kind of catastrophe— earthquakes or tsunamis. There must have been something like that to cause people to leave their homeland. They can’t carry everything with them. But they have their memories of what it was. They wanted to live in surroundings that reminded them of their homeland. This is what has fascinated me.

You are known as “Mrs. Philistine.”

In a new excavation report on Ashkelon, Larry Stager sent me a copy inscribed to the “Queen of the Philistines.”

Do you feel that the Philistines were badly treated in the Bible?

Look, they were the enemy. They were the “other.”

Do you like them personally?

Yes. I think they had good taste. But I never really thought about if I liked them or if I don’t like them. I like them because I like what they led me to. I was very fortunate. I was led to them and I followed them, and they brought me into a subject that I was interested in: the end of the Late Bronze Age in the Mediterranean. There’s trade all around, and then something happens: Trade stops.

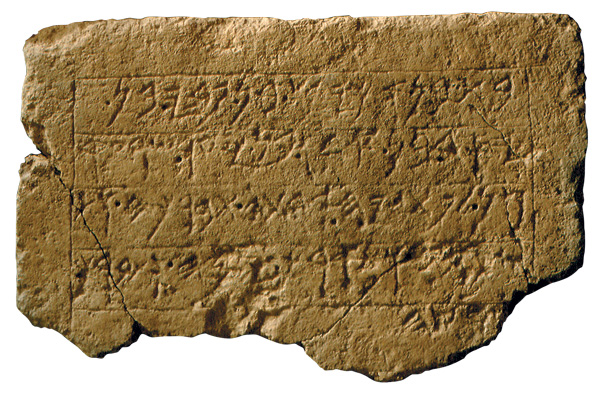

Do you think we should call what we’re talking about Biblical archaeology?

I’ve never really cared about this. I think we learn a lot from the Bible. But I’m not a Biblical archaeologist. On the other hand, you must know your sources. I know the names of the Philistine cities from the Bible, which is a wonderful thing. We were so lucky at Tel Miqne/Ekron. Until the last season [in 1996], we had sherds that indicated it was Ekron, but we didn’t have the final proof. That’s why we went there—because we thought it was Ekron. And we had everything. We found the material culture that said Ekron. And when we found the inscription “Ikausi [Biblical Achish] son of Padi” [Achish was the king of Gath, according to 1 Samuel 21:11 (verse 10 in English)] and the name “Ekron,” then suddenly, there you had the Bible. We went to the site thinking it must be one of the five cities of the Philistines but we never were sure of it [until we found the inscription]. This was very exciting. Yossi Naveh [an expert paleographer] came that night and helped Sy and me to read the inscription. And here you have sa’ar Ekron, “ruler of Ekron.” Here you have archaeology and the Bible, definitely. I’m not a Biblical scholar—I don’t pretend to be—but on the other hand, I think it’s very important to know it. But it is important not to be carried away—not politically and not in any other way.

How does the Bible affect what you do archaeologically?

I’m not one who goes on a dig with the Bible in one hand and my patische in the other. But I think you have to like history, you have to know it and use the sources. I don’t consider myself an expert on the Bible, so I always try to go to the experts, to the people who really understand the Bible more than I.

What was your most exciting find?

It’s not just one exciting find. If you have an idea that you want to explore, that’s exciting. That’s why I went to Cyprus to dig. Athienou was a fantastic site. We dug there [in Cyprus] for two seasons.

Athienou was a kind of open shrine with thousands of votive vessels. There was nothing that would link us to the Sea People or the Philistines. But then we got lucky. I think it was the second season, we found a sherd, a fragment that looked like a Philistine vessel, so then really, suddenly we had this link.

But I have found many exciting things. For example, the lion at Hazor. There were apparently two large stone lions from the Late Bronze Age (13th century B.C.) on either side of the entrance to the temple. I found the one that was buried. It was one of those amazing finds. Why did they bury it? Who did it? It was buried intentionally. When the Israelites came there, they didn’t want to see the lion. So they buried it. And it was really a piece of art. We have very little sculpture, very little art in this country. You go to Egypt, and there you have everything. But here we have very little. So this lion was really very exciting. Years later, Amnon [Ben-Tor] went back to [excavate] Hazor. One night he called me and said, “Trude, I have to tell you, we have always looked for the second lion. I found the second lion.” That was very, very nice. He found it reused, in a later wall. Both lions are standing now in the Israel Museum.

Who do you think made the lion?

It was made locally.

By the Canaanites?

I guess so. The stone itself is not brought from outside. But it is so well done.

What do you think was the significance to the Canaanites of this lion?

This is power. The lions were standing on either side of the entrance to the temple. We know it from all over. Wherever you go in the ancient world, the lion is always a sign of power.

Did the Israelites also use the lion as a sign of power?

Later they used it, but not in architecture. They used it in small pieces of ivory.

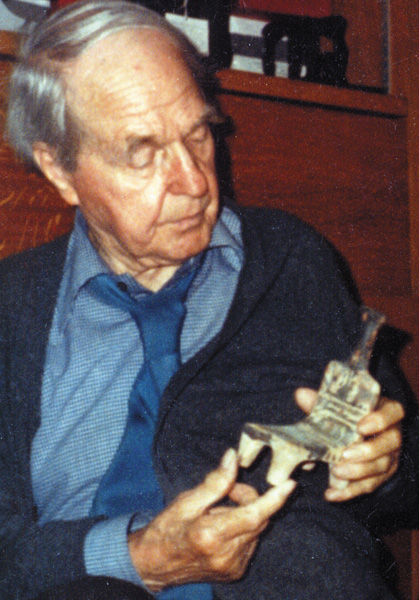

What about the Ashdoda?

Moshe [my husband] found it at Ashdod [another Philistine city mentioned in the Bible]. He called me immediately, and I went down to the dig. The Ashdoda is like modern art. It is somehow very modern. It kind of appeals to you. It gives the message of this woman. Actually we know she is a woman only because she has breasts. Otherwise you could not say if she is a man or a woman. And she’s sitting or becoming encouched. The whole idea of it is amazing. It’s very modern in concept. Its appeal is the same as Henry Moore’s sculptures. But what is the idea behind this? What kind of goddess is this?

[Moore] was in the country when Moshe found the Ashdoda. Moshe showed it to him, and he said, “This would have been my masterpiece if I had made it.”

The Ashdoda is highly stylized art: a goddess in the shape of a chair.

It’s sometimes said that Israel is the most excavated country in the world. An enormous amount of archaeological work goes on here. If you could create the world, would you dig outside of Israel more?

I think it’s always important for us to dig outside Israel. We are such a small country. Actually, we are so lucky to be able to dig our history. You find an inscription and you read it. If you know how to read the [Hebrew] letters, even if they’re different from those today, you read it like Haaretz [an Israeli newspaper]. It’s the same language. It’s unbelievable. Even the names remain. If I go to Ashkelon, it’s [Biblical] Ashkelon. There is something wonderful to be digging up your own past.

Is it a restriction that Israelis can’t dig in Syria, for example?

I’d love to go to Syria, just to see the sites; to go to sites that I’m always quoting—to Ugarit and all the others. But we can’t. It’s a pity.

Israel and Jordan have signed a peace treaty, but there’s really very little cooperation between Jordanian archaeologists and Israeli archaeologists.

Unfortunately. There is some, but more is needed.

Why do you suppose that is?

It’s not because of the archaeology: It’s because of the politics. I hope it will change.

Can you speculate a little bit, what’s going to happen to archaeology in the next 35 years? How will it change?

I think the trend is toward using the sciences more. This is good.

What do you think about the enormous size of the dig reports that are coming out now?

I think it’s terrible. I think when we published the small Qedem volumes that we did, it’s human. We had small ones and big ones, but definitely not like the books they are putting out now. They are getting larger and larger, but we have so much more to report on, including all kinds of new scientific analyses. What is also needed to accompany these large reports are short summary volumes that highlight the major results.

Thank you, Trude.