Israelite Footprints

Has Adam Zertal Found the Biblical Altar on Mt. Ebal and the Footprints of the Israelites Settling the Promised Land?

Adam Zertal discovered a Late Bronze Age/Iron Age I structure on Mt. Ebal. This was during the early days of his survey of Manasseh. The lower stratum of the rectangular structure (Stratum 2) was built on bedrock. A 6-foot-wide circular depression in the middle contained a layer of ash and charred animal bones. The discovery nearby of a chalice, along with scattered hearths, excessive ash, potsherds and animal bones suggests that this was a small cultic site where offerings were made. A four-room house, located to the northwest, may have been used by the Israelites who serviced the site.

In the upper stratum (Stratum 1B, dating to the end of the 13th or beginning of the 12th century B.C.E.), a monumental rectilinear structure of unhewn stones was built above the earlier construction. Measuring about 30 by 23 feet, it has no floor or entrance and seems to have been deliberately filled with layers of bones of male bulls, caprovids and fallow deer, as well as ash and Iron I pottery (including one whole collared-rim jar characteristic of Israelites of the period). Many of the bones had been butchered at the joints and roasted in an open flame.

A ramp, about 5 feet wide, leads up to the top of the structure. Paved courtyards, located on either side of this ramp, included numerous stone installations filled with bones, ash, jars, jugs, juglets and pyxides.

Zertal interpreted the site as cultic, a bamah (a cultic site or “high place”) on which ritual ceremonies took place. In 1985 he suggested that the main structure of the later level may be associated with the altar referred to in Joshua 8:30 and that it may have served as a central sanctuary for the early Israelites—“At that time Joshua built an altar to the Lord, the God of Israel, on Mt. Ebal, as Moses, the servant of the Lord, had commanded” (Joshua 8:30–31).a

Zertal’s critics were numerous and vociferous. Aharon Kempinski, one of Israel’s leading archaeologists, declared in BAR that the structure was nothing but a watchtower.b Anson Rainey, another leading Israeli archaeologist, said it was simply a “house,” adding that Zertal’s claim was a “blatant phony.” William Dever, a leading American archaeologist, chimed in, too,c and Zertal responded in kind.d

Although the association with the passage from Joshua remains controversial, it is now generally recognized that it is a cult site. As recently stated by Amihai Mazar, another prominent Israeli archaeologist:

Zertal may be wrong in the details of his interpretation, but it is tempting to accept his view concerning the basic cultic nature of the site and its possible relationship to the Biblical tradition. This tradition came to us indeed in the framework of Deuteronomistic literature of a much later date, but it is very possible that this literature preserved old traditions, which go back to the period of the [Israelite] settlement. The Biblical references to the sanctity of Mt. Ebal could be one of these old traditions.1

The absence of remains on Mt. Ebal from the monarchical period may reinforce the antiquity of the Biblical traditions about the site in Joshua and Deuteronomy (Deuteronomy 11:29; 27:4–8; Joshua 8:30–35).

In order to assess fully the Ebal site, it must be examined in the broader context of the archaeological surveys of the Land of Israel, especially the territory of Manasseh. As I have written: “When the Mt. Ebal site is set on the larger stage of the Israelite settlement, its origin is seen to be consistent with the dramatic settlement activity in the central hill country during the transition from the Late Bronze Age to the Iron Age I.”2 From an archaeological viewpoint, the site appears to have had an important role in the early religious life of the central hill country settlers.

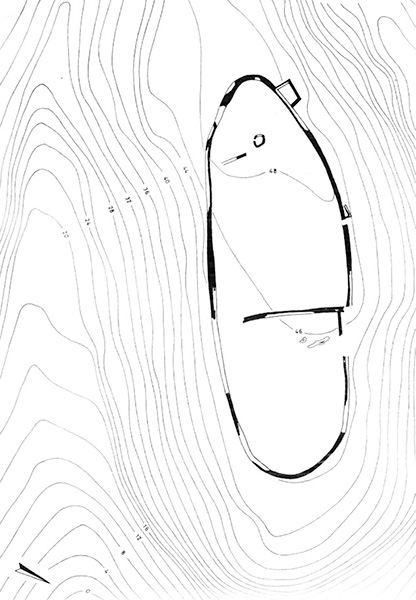

If anything, Zertal’s interpretation of his sandal-shaped sites (more recently foot-shaped enclosures) is even more controversial. These are a series of sites from his Manasseh survey that are mystifyingly enclosed in the shape of a footprint or a sandal, and among them is the Mt. Ebal site.

In his preliminary report on the Mt. Ebal site, Zertal made no reference to anything distinctive about the shape of the site’s enclosure wall. Beginning in 1983, however, his survey of Manasseh had begun discovering sites, all in the Jordan Valley, whose enclosures are in the shape of a footprint, the shape of which was not directed by the topography.

For example, el-’Unuq is enclosed in an elliptical wall of about four acres on an isolated hilltop. This well-built enclosure wall of large unworked field stones is subdivided into two unequal parts. The wall seems too monumental to have been designed for corralling sheep or for agricultural purposes. Large amounts of pottery found there were very similar to that at Mt. Ebal.

East of el-’Unuq, near the Jordan River road, is a similar foot- or sandal-shaped site, Bedhat esh-Sha’ab, of just 3 acres. Here, too, large amounts of early Iron Age I pottery dating to the late 13th and early 12th centuries B.C.E. were recovered.

About a half dozen other similar enclosures have been located in the Jordan Valley. All contain Iron Age I pottery, even though the pottery is relatively scarce.

The paucity of pottery, along with a complete lack of buildings inside the enclosures, suggests that these sites were not designed as dwelling places. Yet they are too large and well built to have served as animal pens.

They seem to be unique and appear to have been built by semi-nomads who used a pottery repertoire similar to that of the new population group that entered Canaan from the east at this time.

The Bible refers to at least three, and possibly five, different locations as “Gilgal” (the Hebrew name, gilgal, seems to mean something like a “circle [of stones]”). Most of these gilgalim (plural of gilgal) appear to have had a cultic function. One gilgal served as the site of the circumcision of the generation of Hebrews born during the wilderness wanderings as well as their celebration of the Passover (Joshua 5:2–11). Another gilgal was located near Mt. Ebal and Mt. Gerizim, where the Israelites renewed their covenant with Yahweh in the midst of the settlement (Deuteronomy 11:30). A gilgal was situated where the Israelites camped and from which they launched their sorties during the period of the settlement, and where the tribal territories were allotted.3 A gilgal became an important cultic center during the time of Samuel, and a gilgal was the place where some men of Judah welcomed David back from exile following his son Absalom’s death (1 Samuel 7:16; 2 Samuel 19:15). Gilgal is not mentioned again until it appears in the Minor Prophets. A gilgal is a site of apostate worship in Hosea and Amos (Micah 6:5; Hosea 4:15; 9:15; 12:11; Amos 4:4–5; 5:5).

To explain the shape of these sites as a foot or sandal, Zertal pointed to the custom of putting a foot on someone or something to make a statement about it. In battle, victors would often put their feet on the necks of those they vanquished to show that they had subjugated them (Joshua 10:24). Treading on territory could symbolize ownership of it (Deuteronomy 11:24), and apparently this symbol evolved into the idea of the foot—or sandal—as a symbol of ownership. When Ruth’s next-of-kin transferred his right of redemption to Boaz, he took off his sandal to show that he was relinquishing it. The Biblical text states that this was the tradition at the time (Ruth 4:7). In light of these and other data, Zertal suggested that the shape of the gilgalim as sandals or feet symbolized the migrants’ belief that they owned the territory on which they built these enclosures.4

When I first saw these sites in the winter of 2007, I immediately thought of the massive footprints, each three feet long, carved into the limestone slabs lining the floor of the portico at the ‘Ain Dara temple in northern Syria.e The footprints at ‘Ain Dara probably symbolized the deity entering the temple. Could it be that the gilgalim, in the shape of footprints, that Adam Zertal discovered were intended to symbolize Yahweh, the deity of the new migrants, striding into his land?

Whether Zertal’s suggestions will gain any traction is questionable. That they will continue to be controversial, however, is undeniable. That they are intriguing and enriching is certain.