Based on reactions from readers, I’m told, one of the most popular articles ever published in BAR identified the figures in the Hebrew Bible who have been confirmed in historical and archaeological sources.a People were fascinated by the fact that 50 people were accordingly confirmed. A later BAR article added three more people in the Hebrew Bible to those 50.b

The question naturally arose: What about the New Testament? What historical evidence outside the New Testament and not produced by Christians refers to people mentioned in the New Testament?

Here I begin to answer this question by presenting New Testament political figures who have been confirmed by extra-Biblical inscriptions and ancient writings. For a collection of writings usually seen as religious, the New Testament mentions a surprising number of political figures, in connection with court trials, dates of important events and even political murders. A follow-up article is planned to include about a half-dozen nonpolitical figures in the New Testament whose existence is confirmed outside its pages; those people all happen to be religious figures. Since Jesus’ confirmation outside the New Testament has already been treated in a previous article,c that article, along with this one and the coming article, should together cover all persons in the New Testament whose existence is confirmed in ancient writings and archaeological discoveries.

In order to understand who the political figures were in the New Testament, we must have a basic grasp of one particular family of rulers—the Herodian family, which was nestled under the wing of the Roman Empire and protected by its military might and served as its regional surrogates. This family consisted of Herod the Great (r. 47–4 B.C.E., initially ruling Galilee only and later all of Roman Palestine, called Palaestina) and his descendants (some also had Herod as part of their name). He was a politically talented son of Antipater II, the son of Antipater I (or Antipas), an Idumean noble. (Idumeans were descendants of the ancient Edomites, who lived south of Israel.) Herod the Great advanced his political career by currying favor with Roman leaders, especially Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus. It was this Herodian family that persecuted or executed many people, whether ordinary Jews, John the Baptist, Jesus or some of Jesus’ earliest followers.

Charts of the family tree of Herod the Great can list up to 80 people and often include multiple persons who had the same name, such as Herod, Berenice, Agrippa, Alexander, Antipas, Salome and so on. To avoid confusion, the following excerpts from the “story line” can help readers keep track of people who are important in New Testament events.

When magi (wise men) from the east came to Jerusalem looking for a child who was born “king of the Jews” (Matthew 2:1–2; see also Luke 1:5), it was the elderly Herod the Great who carefully questioned them. This Herod, upon whom Rome had bestowed the title “the King of the Jews,” wanted to locate, identify and assassinate his new rival. Using the chronological information he had gained from the magi, this Herod killed all the boys born in and around Bethlehem who were two years old or younger (Matthew 2:16–18). Not long after that deed, known as “the massacre of the innocents,” he himself died in 4 B.C.E.

Herod the Great had ten wives, of whom we have the names of only eight. As shown on the accompanying chart of portions of his family tree, three of these wives were especially significant for New Testament events, for the most part because their offspring were involved in summary executions or extended court trials of early leaders of what became the Christian movement.

The Herodias mentioned in the New Testament was a granddaughter of Herod the Great. A well-known episode recorded in Matthew 14:3–12 and Mark 6:17–29 tells how Herod Antipas (r. 4 B.C.E.–39 C.E.), this Herodias’s uncle and second husband, ended up executing John the Baptist. When Antipas married Herodias, her previous husband, his half-brother Philip, was still living—a marriage forbidden in the law of Moses while his brother was still alive. John the Baptist rebuked Antipas for that, and Antipas responded by imprisoning John. Later, Herod Antipas threw a birthday party for himself, as rulers did. Herodias’s daughter Salome danced before him. Enthralled and perhaps drunk, he rashly promised to give her anything she asked, up to half his kingdom. Salome consulted her mother, who told her to ask for the head of John the Baptist on a platter. Although Antipas was reluctant to kill John, in order to avoid embarrassing himself in front of his guests, he had John the Baptist beheaded in prison. Herod Antipas is also the Herod who is mentioned in the Gospels during the public ministry and multi-phase court trial of Jesus.

The Jewish historian Josephus tells us that earlier, a neighboring ruler, King Aretas IV of Nabatea, had given his daughter in marriage as Antipas’s first wife. But when she secretly learned that Antipas intended to divorce her and marry his half-brother’s wife, Herodias, she fled back to her father. This offense and a boundary dispute led Aretas to attack Antipas. As Josephus relates, “All Herod’s army was destroyed … Now, some of the Jews thought that the destruction of Herod’s army came from God, and that very justly, as a punishment of what he did against John, that was called the Baptist.”?1 This Aretas is mentioned in 2 Corinthians 11:32, which describes events long after Paul’s conversion.

It was Herodias’s brother, Herod Agrippa I (r. 37–44 C.E.), who executed James the son of Zebedee without a trial and imprisoned Peter, though Peter miraculously escaped (Acts 12:1–19). The Book of Acts states that Agrippa I’s motive was to gain political favor with religious leaders. Because there are several Jameses in the New Testament, we should note that Jesus had called this James and his brother John, sons of Zebedee, to be his disciples as they tended their fishnets by the Sea of Galilee. (Later they were known as “the sons of thunder.”) Jesus had also included this James with Peter and John in his inner circle. He was the first of Jesus’ original 12 chosen followers to be executed.

Later, when certain Jewish leaders brought charges against the apostle Paul, the Roman governor Antonius Felix (r. 52–59 C.E.) presided over the initial hearings in Paul’s trial. Felix was the second husband of Drusilla, a sister of the Herodias mentioned above and of Herod Agrippa II (Acts 24:24). Then Felix left Paul in prison for two years until his successor, the Roman governor Porcius Festus (r. c. 60–62 C.E.), arrived and presided over the trial (Acts 24:27).

As Festus continued the trial, he received a visit from the son of King Herod Agrippa I, King Herod Agrippa II (r. 50–c. 93 C.E.), with his sister (and rumored lover) Berenice. When they attended Paul’s trial (Acts 25:1–26:32), Festus had Paul plead his case to Agrippa II, because Agrippa was familiar with Jewish customs and controversies. Paul even mentioned that Agrippa believed the prophets. Agrippa later confided to Festus that Paul could have been set free if he had not appealed to Caesar. Festus honored Paul’s appeal by sending him to Rome.

The actions of King Herod Agrippa I in executing James without a trial, followed by the actions of the Roman governors Felix and Festus in conducting the trial of Paul the Apostle, form a sinister parallel to Herod Antipas previously executing John the Baptist without a trial and conducting one phase of Jesus’ trial.

This article does not attempt to mention every last bit of evidence for each political figure—not every coin series and not every ancient writing that mentions them. But in a table it lists some of each available kind of evidence in order to make clear a strong case for the confirmation of at least 23 political figures in the New Testament in ancient writings and in archaeological discoveries.

Regarding archaeology, this article bases its conclusions only on materials that are known to be authentic, not items from the antiquities market, because as a rule, there is a possibility that they might have been forged and are unreliable. The confirmations below avoid speculation and seek to be conservative in the interpretation of evidence in order to ensure trustworthiness.

The writings of Flavius Josephus (37/38–c. 100 C.E.), especially his books Antiquities of the Jews and War of the Jews, provide sufficient and in many cases abundant first-century C.E. documentation for 22 of the 23 New Testament political figures listed below.

The one exception is Gallio, proconsul of Achaia/Achaea, in Greece. As a native of Palestine, a Pharisee and a member of a priestly, aristocratic family (his mother was a descendant of Israel’s earlier Hasmonean rulers), Josephus was qualified to write of the political figures in the Levant, rather than Greece, because many of the political figures he wrote about were not only his countrymen, but also his contemporaries or near-contemporaries. But of course, historians, archaeologists and Bible scholars seek all available evidence, so inscriptions in stone and on coins are included here.

To begin, the four emperors mentioned in the New Testament are all abundantly verified in the writings of Roman historians, such as Tacitus’s Annals, which mentions all four, as well as in Josephus’s writings and in many inscriptions. For these, no further verification is needed: Caesar Augustus (r. 31 B.C.E.–14 C.E.; earlier name: Octavian) is mentioned in Luke 2:1 as ruling when Jesus was born; Tiberius (r. 14–37 C.E.), to whom Luke 3:1 refers, was emperor from before Jesus’ baptism until well after his crucifixion; Claudius (r. 41–54 C.E.) was emperor when the great famine occurred that had been predicted by the Christian prophet Agabus (Acts 11:27–28); Nero (r. 54–68 C.E.) is not named in the New Testament, but simply called “Caesar” in Acts 25:10; Acts 28:19. (Gaius, nicknamed “Caligula,” the Roman emperor after Tiberius, goes unmentioned in the New Testament.)

Turning from these four Roman emperors who have been confirmed, we have a number of Herodian political figures mentioned in inscriptions and histories.

King Herod I the Great’s archaeological confirmation is found in his name and title written in Greek on the many coins that he minted, including 393 of his coins discovered at Masada plus smaller quantities at locations such as Meiron, Herodium, Tel Anafa and Caesarea Maritima.

Herod Archelaus, Ethnarch of Judea, Idumea and Samaria, is the only Herod in Palestine who held the title of ethnarch, meaning “ruler of a nation.” Caesar Augustus cautiously withheld from him the title of king, and, indeed, Archelaus’s reign so infuriated the populace that he was replaced by Roman governors for direct rule by Rome. Archelaus is confirmed archaeologically by his many coins, notably 176 discovered at Masada. In the inscriptions in Greek on all his coins, he calls himself only “Herod” or “Herod the Ethnarch” (sometimes abbreviated), never using his name, Archelaus. Archelaus’s coins have been discovered in various parts of Palestine, including Galilee and Transjordan.

As for Herod Antipas, archaeology confirms his rule and title of Tetrarch (of Galilee and Perea) on several coins with the inscription “Of Herod the Tetrarch” in Greek, without giving his name, Antipas. Also inscribed on some of his coins is the name of a city, “Tiberias,” which Antipas founded in Galilee and where he built a mint that produced these coins. Josephus’s writings and modern analysis of Jewish coins reveal that the only tetrarch named Herod who ever ruled Galilee was Herod Antipas. Almost all of Antipas’s coins whose place of discovery is known have been found near Tiberias, though one was discovered in Jerusalem.

Philip the Tetrarch (of Trachonitis, Iturea and other northern portions of Herod the Great’s previous realm) is the one who built up the city of Caesarea Philippi, “Philip’s Caesarea,” ancient Paneas, also called Banias. It was in sight of this city that Peter confessed his faith in Jesus as the Messiah (Matthew 16:16). Philip the Tetrarch is confirmed by his coins, most of which were discovered in his own kingdom, though a few have been found at Meiron and Tel Anafa and one as far as Cyprus. Philip did not have to avoid portraits on his coins because his subjects were generally not Jewish and had no religious prohibition against graven images.

Salome, Herodias’s daughter who danced before Herod Antipas, was the grandniece and eventually the wife of Philip the Tetrarch. She outlived him and is pictured and named on a coin attributed to her second husband, Aristobulus, King of Chalcis. Although her name does not appear in the New Testament, we learn it from Josephus’s Antiquities.

The coins of King Herod Agrippa I variously show his name, or name and title, in Greek as “Agrippa” or “King Agrippa.” At Masada, 114 of his coins were excavated, as five others were at Meiron. His prutah coins (Jewish coins made of copper with low value), which are distinctive in their decorations and the spelling of his name, have been discovered in and near Jerusalem, as well as in all parts of Palestine, on Cyprus, at Dura-Europos in Syria and even on the acropolis at Athens.

King Herod Agrippa II has also been verified by archaeology, for example, by two coins discovered at Masada and six at Meiron. Quite a few series of his coins bear his name Agrippa, frequently abbreviated, and they can be dated to his reign, rather than his father’s.

Mentioned in the writings of Josephus, but apparently not featured on coins, are certain members of the Herodian establishment. They include: Berenice (or Bernice) and Drusilla, sisters of Herod Agrippa II; Herod Philip, who was not a ruler, but was one of the sons of Herod the Great and was both the half-brother of Herod Antipas and Herodias’s first husband; and Herodias, wife of Herod Philip, then of Herod Antipas, and mother of Salome.

A number of Roman officials, including the notorious Pontius Pilate, are also confirmed by archaeology.d

Quirinius, a Roman legate in Syria-Cilicia (Luke 2:2) who acted as “troubleshooter,” is referred to in the Lapis Venetus, a stone inscription in Latin that describes a census that he ordered in a Syrian city. Apparently he did not have the luxury of issuing any coins. After the disastrous rule of Herod Archelaus inflamed Palestine with anti-Roman sentiment, Quirinius was sent to dispose of Archelaus’s property, restore order, assure the populace of better treatment and prepare the way for Roman governors. That succession of Roman governors eventually included Pontius Pilate.

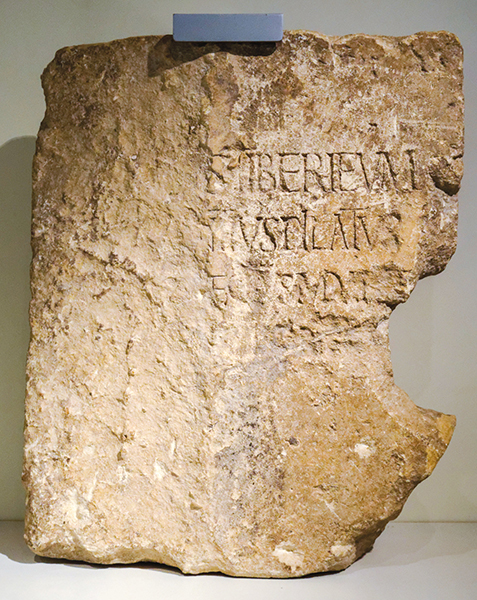

Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect of Judea during the trial and execution of Jesus, is named in a building dedication on the “Pilate Stone” discovered in 1961 in the theater or arena of the ancient city of Caesarea Maritima, on Israel’s northern seacoast. This limestone block—2.7 feet high, 2 feet wide and 0.6 feet thick—was lying face down and used as a step. It had been trimmed down to be reused twice. Two of its four lines read, in English translation, “[Po]ntius Pilate ... [Pref]ect of Juda[ea].”2

The inscription could potentially be dated to any time in Pilate’s career, but a date between 31 and 36 C.E. seems most likely.3 The word for the building dedicated to the emperor Tiberius, “Tiberieum,” is in the first line of writing. On line 2, the family name Pontius was common in central and northern Italy during that era, but the name Pilatus was “extremely rare.”4 Because of the rarity of the name Pilatus, which appears in full, and because only one Pontius Pilatus was ever the Roman governor of Judea, this identification should be regarded as completely certain and redundantly assured even beyond that by such “extra” data.

As with other Roman governors, the coins Pilate issued do not have his name on them, but rather display only the name of the Roman emperor, in this case Tiberius, observable among the 123 discovered at Masada, one at Caesarea Maritima and one at Herodium.

Antonius Felix, a Roman procurator who governed when Claudius was emperor, followed the custom of Roman governors, issuing coins like Pilate’s in that none of them display his name. But they are identifiable as his because they display the name and regnal year of the emperor. Several also have the name of the empress, Julia Agrippina. Examples of his coins are from Masada, Meiron, Herodium and Caesarea Maritima.

Porcius Festus, the Roman procurator who governed immediately after Felix, during the reign of the emperor Nero, also minted coins in the custom of Roman governors, which do not show his name. These include 184 discovered at Masada. Still, as with Felix, we can identify which are his by using other data, particularly the name and regnal year of the emperor.

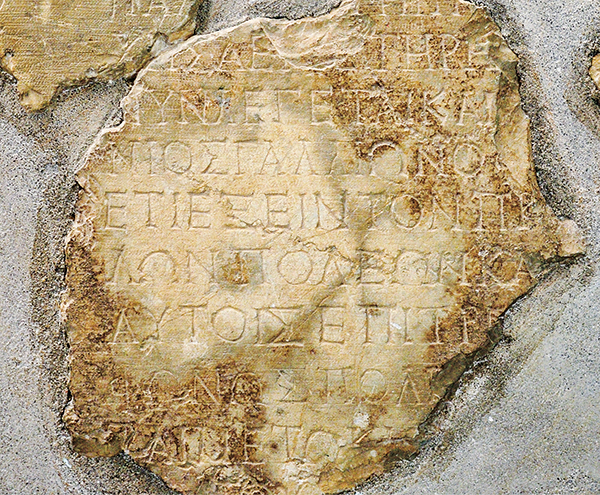

Lucius Junius Gallio, proconsul of Achaia (r. c. 51–55 C.E.; Acts 18:12–17), was the judge who heard the accusations against Paul the Apostle when he first visited Corinth. Although Josephus does not mention him, this same Gallio is referred to in an inscription discovered in the late 19th century at Delphi in Greece. Carved into a stone now broken into fragments, with some words missing, it takes the form of a letter from the Roman emperor Claudius and includes a date.

The final three New Testament political figures confirmed by extra-Biblical evidence are independent political figures from Nabatea, Egypt and Galilee.

King Aretas IV (r. 9 B.C.E.–40 C.E.; 2 Corinthians 11:32) was a contemporary of Herod Antipas. As king of the Arabian kingdom of Nabatea, he ruled a buffer state between the Roman Empire and the Parthians. During his reign, Nabatea reached the height of its power and wealth through trade and political influence. The coins Aretas minted have been found far and wide, from Masada to Cyprus, from Dura-Europos in what is now eastern Syria to Susa in Persia (present-day Iran).

Aside from coins, stationary inscriptions that name King Aretas and members of his immediate family have been discovered south of the Dead Sea at Petra, at Avdat (Obodat) in southern Israel and even at Puteoli in Italy.

A very different political figure is the unnamed Egyptian leader who escaped after his violent uprising was suppressed by the Roman governor Felix. Because this leader was still at large, the Roman commander who rescued Paul the Apostle from a mob in Jerusalem began to suspect that Paul might be this man (Acts 21:38).

Although neither Josephus nor the Book of Acts gives the name of the leader of the insurrection, he can be identified by the following marks of an individual that are found both in Josephus’s writings and in the corresponding quotation from the Roman commander in Acts 21:38: (1) He was an Egyptian; (2) he led thousands of men in a rebellion (4,000 in Acts; 30,000 according to Josephus, but Josephus can be shown to have inflated some of his numbers); (3) he led his forces out into the wilderness; and (4) it was reasonable to think that he might appear in or around Jerusalem. The leader of the insurrection escaped near Jerusalem, according to Josephus, and this fact is implicit in the accusation of the Roman commander during his conversation with Paul in Jerusalem: that Paul might be the same man (Acts 21:38).

The setting (time period and place) is the same in Acts and in Josephus’s writings: It was during the administration of Felix that the Roman commander and Paul met in Jerusalem (Acts 23:24), and Josephus wrote that it was Felix who defeated the forces of the rebellion at Jerusalem.

Judas of Galilee (sometimes translated Judas the Galilean) was mentioned by a religious figure, Gamaliel, grandson of Hillel, in his cautionary speech to the Jerusalem sanhedrin that apparently saved the apostles’ lives (Acts 5:37). Josephus also wrote in several places about the same Judas of Galilee as the leader of the rebellion against Cyrenius (also spelled Quirinius), who is identified above because of Cyrenius’s census and taxation, which scholars usually date to 6 C.E.

The above-mentioned two leaders of insurrections against Roman rule who appear in the New Testament were defeated before they could become established enough to have their names inscribed on coins, monuments, etc. Therefore, outside of the New Testament, they appear only in ancient history, notably that of Josephus.

One “almost real” (not certain, but reasonable) candidate for identification in an inscription is Lysanias, Tetrarch of Abilene. His identity is not clear enough in a relevant inscription to be certain he is the one referred to in Luke 3:1, but it is reasonable enough for some scholars to consider a New Testament identification probable. According to a dedicatory inscription carved in stone at Abila, capital of the ancient tetrarchy of Abilene, a certain “Lysanias the Tetrarch, a freedman” ruled there.5 In line 1, the “august lords” are most likely Emperor Tiberius and Tiberius’s mother, Livia, who was granted the title Augusta in 14 C.E. and died in 29 C.E.6 Luke 3:1 dates the beginning of the ministry of John the Baptist using dates established with reference to several rulers, including Lysanias. By referring to these rulers and to other events, many scholars place the start of John’s ministry at c. 28 C.E., which falls within the potential time span of the tetrarchy of the Lysanias in this inscription. On the other hand, the dates used are somewhat imprecise, and the date of the inscription is based on likelihood, rather than complete clarity. If the “august lords” were Nero and his mother Agrippina, then this Lysanias’s rule might have lasted as late as the reign of Nero (54–68 C.E.).

In Josephus’s Antiquities, the reference to “Abila of Lysanias” is too vague in its time reference to be a confirmation of Luke 3:1. Lysanias, Tetrarch of Abilene, must not be confused with the earlier Lysanias, a Tetrarch in the same area, who is also mentioned in Antiquities.

There are a few inscriptions and writings that might, at first sight, seem to refer to New Testament political figures, but on closer examination—especially after comparing the historical background of the New Testament figure with that of the person in the inscription—it turns out that they cannot be clearly identified.

All 23 of the political figures discussed in this article are clearly identifiable in sources outside the New Testament, confirming this facet of its historical reliability.