Epistles: When Did Literacy Emerge in Judah?

When were biblical traditions first put down into writing?

According to the current consensus among scholars, it was in the eighth century B.C.E. at the earliest. Indeed, in archaeologist Israel Finkelstein’s words, “Writing is not in evidence in Judah before around 800 B.C.E.”1 Likewise, biblical scholar John Van Seters wrote a few years ago, “Not until the late eighth century was Judah sufficiently advanced as a state that it could produce any written records.”2 Similar doubts concern the kingdom of Israel, so it looks as though we have a relatively precise terminus a quo (earliest possible date) for the composition of any Hebrew literature.

However, current knowledge in epigraphy and archaeology leads us to call this conventional wisdom into question.3 Indeed, the main reasons that underlie it prove ill founded.

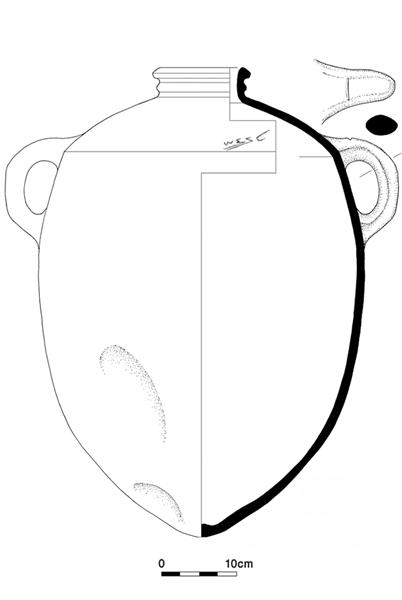

First, it is true that there is a dearth of alphabetic inscriptions from Judah and Israel dated to the tenth or ninth centuries compared to later periods—although one does occasionally find such texts, such as in Jerusalem in 2012, on a pithos from the Ophel (the area immediately south of the Temple Mount). However, many epigraphists will argue that there is no simple correlation between the quantity of discovered texts and the number of documents that actually existed. We have hundreds of Hebrew seals and bullae from the ninth to sixth centuries, pointing to the existence of hundreds of papyri, and yet only one such papyrus from this period has ever been found, in a cave in the Wadi Muraba‘at, near the Dead Sea.a

In fact, papyrus and leather, the normal media for literary texts, did not survive the climate of Palestine, except in caves, like those which housed the Dead Sea Scrolls. We have statistics for Greek and Latin papyri: 50,000 have been found of Egyptian provenance, but only 600 originating in the Near East (including those found in Egypt!).

The increase of inscriptions in the late part of the royal period, compared to its beginning, may well reflect a general increase in the production of texts. However, the nature of the findings (mainly ostraca, everyday documents) is largely irrelevant with regard to literature.

A comparison with the Persian period (539–330 B.C.E.) is also telling. Although it is currently regarded by many as the most important time for the composition of biblical texts, not a single papyrus or parchment has been found from this chronological horizon in Judea (Persian Yehud)—only short inscriptions. Thus, even a “productive” period could leave no trace of its literature.

The second argument often put forward runs like a syllogism:

(1) A society must reach a certain “level of development” to be able to produce literary texts.

(2) Judah did not develop before the eighth century B.C.E.

(3) Therefore, Judah did not produce literature until the eighth century.

However, both premises are doubtful. Regarding the second point, although some scholars categorically assert that Jerusalem was an insignificant town before 800 B.C.E., it would be an understatement to say that the archaeological profile of this city in the early monarchy is a subject of intense debate among scholars, as BAR readers know well.b Any discussion about the production of literature based on this issue would be precarious at best.

In any case, the first premise—that is, the supposed correlation between the “level of development” (assuming it could be assessed) and the existence of literature—has never been proven. In fact, it cannot be proved in the context of ancient Israel since one parameter, the presence of literature, is in large part undetectable by archaeological means. In addition, there are possible counter-examples, like Moab in the ninth century, where the long text on the Mesha Stela was written.

So there is no convincing reason to deny that Israelites were able to put down in writing long, literary compositions as early as the beginning of the first millennium B.C.E. But there is more: We have positive hints suggesting that they did so.

First of all, despite the paucity of our documentation, there are traces of an uninterrupted alphabetic scribal tradition stretching from the second to the first millennium B.C.E. The “Early Canaanite” script, which is the first alphabet, was apparently invented by Canaanites working in the Egyptian administration in the early second millennium B.C.E. It is attested notably on the so-called Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions from Serabit el-Khadem, and its letterforms were inspired by hieroglyphic signs. The script of the famous Qeiyafa ostracon, dated c. 1000 B.C.E., is a late witness to this tradition.

This script was normalized in the 11th century in Byblos (hence the Phoenician alphabet) and in the tenth or early ninth century at the latest in the southern Levant. It became unidirectional (going right to left), while the shape and the stance of the letters were standardized. These are hallmarks of a script used for lengthy literary texts.

Moreover, Israelite scribes developed a “national” script, the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, around the first half of the ninth century, which would be quite unexpected if they were content to scribble short inscriptions. This rather points to an organized scribal apparatus producing long texts. Furthermore, epigraphist Benjamin Sass has recently noted that the script of some early ninth-century inscriptions found at Tel Rehov in the Jordan Valley and at Megiddo bear cursive features. Such features in the shape of letters develop when scribes write quickly on mediums like papyrus and leather.

For the same reason, Finkelstein himself now admits that literary compositions were possible in Israel in the ninth century B.C.E.4 Note that according to archaeologist Amihai Mazar’s chronology, some of these inscriptions might date from the tenth century.5 Since cursive features are probably the result of decades of fast writing, they may point in any case to fast writing already in the tenth century.

All this should not be construed as a proof that biblical texts or their sources were written in the tenth or ninth century, although it makes it possible. Perhaps entirely different narratives or poetic works—about Ba‘al for instance—were in circulation!