Everybody knows the biblical story of David and Goliath. Most will even recall that the young shepherd used a sling to take down the Philistine champion, with a single cast of stone (1 Samuel 17). But how credible is this episode? What do we know about how ancient slings were made, what ammunition was used, how far and accurately they could shoot, and how much damage they could inflict?1

David’s sling was not what we today call a “slingshot”—a Y-shaped stick or other implement to which are attached two elastic cords and a pouch, and which propels an object by stretching and releasing the cords. By contrast, a typical ancient sling was a pouch with a long cord attached at each end, made from some durable, flexible, but non-stretchable material. While holding both cords, the slinger placed an object in the pouch and then created centrifugal force by whirling the sling overhead or to the side. Releasing one cord then launched the projectile through the air.

Throughout history, people have made slings from some type of flexible, natural material—typically from animals (hair, wool, leather) or plants (hemp, flax). Logically, David would have woven his sling from the wool of the sheep he was herding, and his sling may have followed the simple, classic pattern of a woven pouch connected to two cords. Often, one cord ended in a loop that the slinger slid over a finger on the slinging hand, so that when the other cord was released, the sling stayed attached to the hand.

Made of organic materials, most ancient slings decomposed over time, leaving only artistic and literary evidence to inform us about their construction. Only a handful of ancient slings have survived, such as examples preserved in the arid conditions of Egypt.

Although the Bible and other ancient texts often mention slingers and slinging, they rarely indicate anything about technique. For example, when David fought Goliath, the text simply says, “David put his hand in his bag, took out a stone, slung it, and struck the Philistine on his forehead” (1 Samuel 17:49). Fortunately, ancient paintings and reliefs offer some clues about methods of slinging.

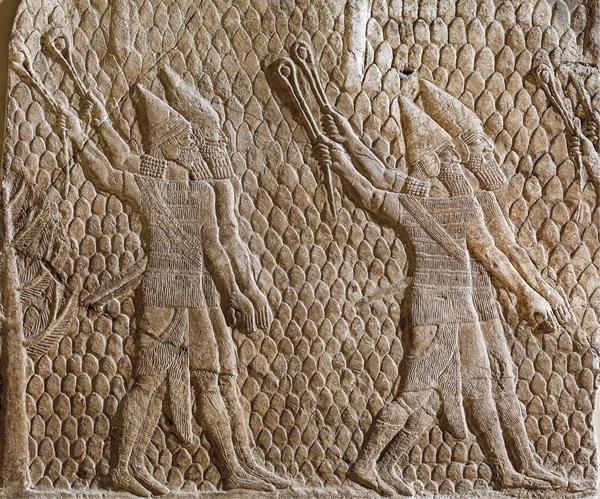

Some pictures appear to show slingers whirling the sling horizontally over their heads, as depicted in an early 12th-century B.C. relief from the mortuary temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu where an Egyptian slinger casts from a crow’s nest atop the mast of a ship, engaged in a naval battle with the Sea Peoples. By contrast, other pictures seem to show slingers whirling their slings vertically at their sides, like the Assyrian and Judahite slingers portrayed in the famous Assyrian reliefs of the battle of Lachish in 701 B.C. (see image in this article).a

Just as we find apparent variety in ancient slinging techniques, so we find a variety of slinging ammunition. The most common sling projectile throughout history has likely been the common fieldstone. However, fieldstones are usually irregular in shape, which often causes them to curve when cast. Thus, as early as the late Neolithic period (c. sixth millennium B.C.), people were shaping sling ammunition out of stone and clay to make it more uniform and aerodynamic.

Shaped, spherical sling stones first appear in the Early Bronze Age (c. 3300–2000 B.C.). In Israel, these were typically fashioned from locally available flint or limestone, usually to a size of 2–3 inches in diameter (about the size of a plum or baseball). Although such shaped stones appear frequently in the archaeological record of Bronze and Iron Age Israel, they are rarely mentioned in texts. The Hebrew Bible, however, includes a rare reference to military production of this type of sling stone in the Kingdom of Judah during the eighth century, saying, “[King] Uzziah provided for all the army … the stones for slinging” (2 Chronicles 26:14).

The ancients also produced sling ammunition from clay as far back as the sixth millennium B.C., as evidenced by finds from northern Mesopotamia. Pure clay, used without chaff or other forms of temper, is dense, easily worked, and makes for good sling ammunition. Clay projectiles were typically sun dried and generally weighed around 1–2 ounces.

Another common type of sling ammunition was brook stones—natural stones rounded by water in streambeds or along shorelines. Such stones fly straighter than irregular fieldstones, which David would have known when he “chose five smooth stones from the wadi [streambed]” as his ammunition before facing Goliath (1 Samuel 17:40).

During the later Hellenistic and Roman periods, sling pellets were also molded from lead. Lead pellets were often shaped like an almond or miniature football and usually weighed 1–2.5 ounces. Many of them bore symbols, such as scorpions, or mocking messages, such as “for Pompey’s backside.”

Whatever their type of ammunition, some of history’s most famous armies, including those of Sennacherib and Julius Caesar, included well-trained slingers. The earliest mention of organized military slingers is in Judges 20:16, with its reference to the 700 left-handed Benjaminites who “could sling a stone at a hair, and not miss.”b By the time of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, armies commonly used slings in battle. In fact, when Israel attacked the Moabite fortress of Kir-hareseth, the biblical writers describe the battle by simply saying, “Slingers surrounded and attacked it” (2 Kings 3:25).

Despite their value, slingers sometimes commanded little respect by other ancient troops, as the simple sling was often viewed as a poor man’s weapon. Well-armored and well-armed infantrymen, who fought hand-to-hand, commanded more respect. Goliath’s disdain for David (1 Samuel 17:42-44) may reflect this common disrespect of slingers.

Just how effective were ancient slingers? Often extremely effective. Numerous authors attest to the range and accuracy of slingers, as well as their ability to inflict damage.

How far could the ancients sling effectively? In the fourth century A.D., the Roman military writer Vegetius (Epitoma 2.23) recommended that Roman slingers and archers practice using targets at a distance of around 600 feet (200 yards), suggesting that they could learn to hit a person at that distance. Writing in the fourth century B.C., the Greek historian Xenophon commented that Rhodian slingers could double the range of Persian slingers (Anabasis 3.3.16), which suggests they may have been able to reach distances of up to 400 yards when slinging at massed troop formations. All this suggests that practiced slingers could have had military effectiveness as far away as 200–400 yards. By comparison, the modern record for slinging distance stands at 550 yards.

Ancient authors and modern tests suggest that a skilled slinger can achieve a very high degree of accuracy at closer range. The Roman historian Livy (first centuries B.C./A.D.) claimed that Achaean slingers “would wound not merely the heads of their enemies but any part of the face at which they might have aimed” (History of Rome 38.29.7), calling to mind David’s successful cast to Goliath’s forehead. A modern ethnographic study notes that Arabian slingers hunt game at 30–50 yards, which likely provides an upper limit for the range at which David could have attacked Goliath.

All this shows the formidable capabilities of the sling, but how did it compare with other projectile weapons? The simplest projectile weapon is a hand-thrown stone, which has an effective range of up to 25 yards. Modern tests show that javelins have an effective range of just over 20 yards. Ancient texts suggest that archers had ranges similar to those of slingers, except that archers could be highly accurate even farther than slings, at up to 70 yards. Thus, since Goliath’s longest-distance weapon was a javelin, his range for engaging David was only about half of that of his underdog challenger.

When it comes to speed and lethal force, the sling’s centrifugal force enables a moderately skilled slinger to launch a projectile at speeds of up to 113 mph and inflict great damage. The Roman medical author Celsus (first centuries B.C./A.D.) wrote that wounds from slings were more dangerous than wounds from arrows, because of the internal damage caused by the blunt force (On Medicine 5.26). Accordingly, the biblical account of David defeating Goliath describes the bone-breaking force of David’s cast by noting that his stone “sank into [Goliath’s] forehead” (1 Samuel 17:49).

Historical sources and modern tests agree that in well-trained hands, the sling is a formidable weapon capable of inflicting a significant amount of damage. Because of their simple design and ammunition, slings were a convenient weapon used by people throughout the ancient world, and rather than merely serving as a useful implement for shepherds or hunters, their range, accuracy, and ability to inflict damage made them an excellent option for a highly accurate or long-range weapon in ancient warfare.

In light of these observations, we can better understand the biblical story of a shepherd skilled with a sling who defeated a highly trained Philistine warrior. Goliath wore armor and was limited by the range of his javelin, and he expressed disdain for his unarmored, simply armed foe. David bore a simple sling and used rounded stones from the nearby streambed for his ammunition. Yet David’s sling provided him the decisive advantage of staying out of range of his opponent’s weapons while still allowing him to hit Goliath’s forehead with enough force to penetrate his skull, so he could take down the giant and then finish him off with his own sword, thereby winning the battle.