The Bible is understandably hostile to the Philistines, describing them as a pleasure loving, warlike society of pagans ruled by “tyrants” who threatened ancient Israel’s existence. An unscrupulous enemy, the Philistines deployed Delilah and her deceitful charm to rob Samson of his power. In a later period, they slew King Saul and his sons in battle, then cruelly hung the king’s headless body from the walls of Beth Shean. And for three millennia now, the rousing story of David’s victory over the awesome Goliath has been told and retold, creating an indelibly negative image of the Philistines in the imagination of each new generation.

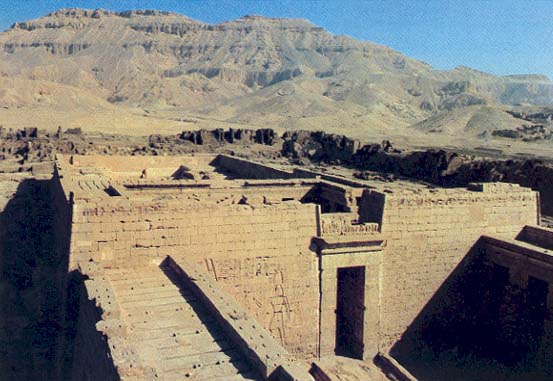

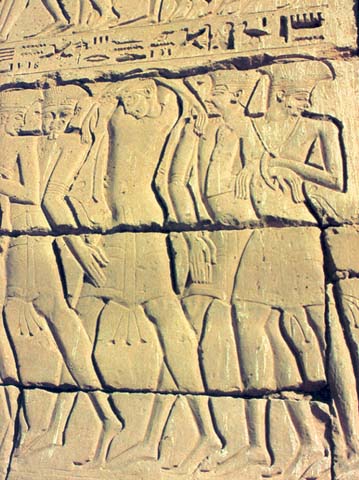

Today, the negative image is entrenched. The dictionary defines a “Philistine” as “ … a crass, prosaic, often priggish individual, guided by material rather than intellectual values; … belonging to a despised class; one deficient in originality or aesthetic sensitivity.” But is this image, in fact, deserved? In order to uncover an accurate picture of the Philistines and the cultural milieu in which they lived, we must clear away many strata of archaeological debris, along with the many layers of misunderstanding and misconceptions that have accumulated over the centuries. In the past 2,000 years, many books have been written about the Philistines, but the “research” on which these books were based was limited primarily to speculation on the Biblical sources. Then in 1821 Jean Francois Champollion deciphered ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics and an intriguing new resource for the study of the Philistines appeared. The war reliefs of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, which could now be read, told a story in words and pictures about the arrival and subsequent defeat of the “Sea Peoples.” Among these invaders were the prst, the Philistines.

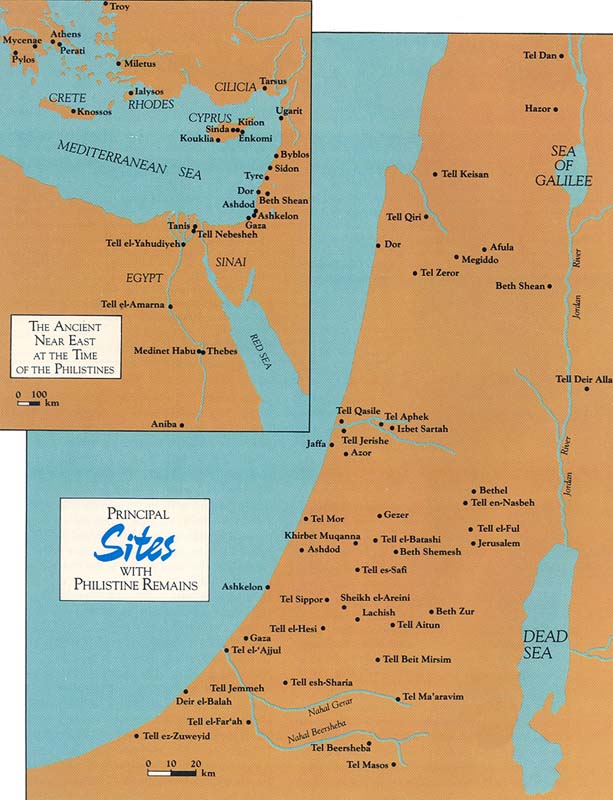

Still later, in the 20th century, archaeology began to reveal a picture of the Philistine settlement in Palestine. (Long after the Philistines had disappeared from the stage of history, Herodotus called their descendants Palastinoi, a name subsequently given to the geographic area called Palestine.) The early pioneering efforts of archaeologists like R. A. S. Macalister at Gezer, Sir William Flinders Petrie at Tell el-Far‘ah (South), and William Foxwell Albright at Tell Beit Mirsim were followed by the more recent and more dramatic discoveries of Philistine towns by Moshe Dothan at Ashdod and by Benjamin Mazar and later by Amihai Mazar at Tell Qasile.

The Sea Peoples, including the Philistines, first appeared in the eastern Mediterranean in the second half of the 13th century B.C. At the time, the Egyptians and the Hittites were in power in the Levant (the Hittite empire centered in Anatolia), but both were weak, politically and militarily. The Sea Peoples exploited this power vacuum by invading areas previously subject to Egyptian and Hittite control. In wave after wave of land and sea assaults they attacked Syria, Palestine, and even Egypt itself. In the last and mightiest wave, the Sea Peoples, including the Philistines, stormed south from Canaan in a land and sea assault on the Egyptian Delta. According to Egyptian sources, including the hieroglyphic account at Medinet Habu, Ramesses III (c. 1198–1166 B.C.) soundly defeated them in the eighth year of his reign. He then permitted them to settle on the southern coastal plain of Palestine. There they developed into an independent political power and a threat both to the disunited Canaanite city-states and to the newly settled Israelites. Philistine culture and military power thrived, principally from the middle of the 12th to the end of the 11th century B.C., exerting a major influence on the history and culture of Canaan. From the end of the 11th century, Philistine influence and cultural distinctiveness waned. Ultimately, it was eclipsed by the rising star of the united Israelite monarchy.

According to inscriptions of Pharaoh Merneptah (c. 1236–1223 B.C.), the Sea Peoples had also attempted to invade Egypt in that monarch’s fifth regnal year, this time from the direction of Libya. The attack was led by Libyans, but joining them were “foreigners from the Sea”—the Sherden, Sheklesh, Tursha (Teresh), and Akawasha. This list of Sea Peoples does not, however, mention the Philistines and the Tjekker. They are mentioned as invaders only later, during the reign of Ramesses III where, as I have said, they are mentioned and pictured in the texts and reliefs of the mortuary temple at Medinet Habu in Thebes.

The vivid battle scenes depicted on the walls of this temple are our most precious and most graphic representation of the Sea Peoples’ dress, weaponry, chariotry, naval equipment, and battle tactics. The accompanying inscriptions are invaluable records of attacks on the Egyptian frontier by foreigners:

“The foreign countries made a conspiracy in their islands. All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms, from Hatti, Kode, Carchemish, Arzawa, and Alashiya on, being cut off at [one time]. … Their confederation was the Philistines, Tjekker, Shekelesh, Denye[n], and Weshesh, land united. They laid their hands upon the lands as far as the circuit of the earth, their hearts confident and trusting ‘Our plans will succeed.’”

After describing his preparations for the great battle with Sea Peoples in the Nile delta, Ramesses relates the results of the conflict:

“Those who came forward together on the sea … were dragged in, enclosed, and prostrated on the beach, killed and made into heaps from tail to head. Their ships and their goods were as if fallen into the water. … The northern countries quivered in their bodies, the Philistines, Tjekk[er, and … ]. … They were teher [chariot] warriors on land; another [group] was on the sea. Those who came on [land were overthrown and killed]. … Those who entered the river-mouths were like birds ensnared in the net.

According to the inscription under the land battle scene, the Egyptian army fought the Sea Peoples in the land of Djahi, the Egyptian term for the Phoenician coast and hinterland down to Palestine.

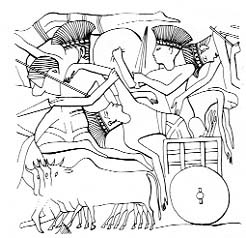

The Philistine camp was composed of three separate units: noncombatant civilians, chariotry, and infantry. The noncombatants, shown in the center of the upper register, included men, women and children riding in slow-moving, two-wheeled carts, each harnessed to a team of four oxen. These carts were very similar to transport wagons still in use today in some parts of Turkey. This picture of the Sea Peoples, invading both by land and sea, reflects their purpose—to occupy and settle the lands they overrun. They were not merely staging a large-scale raid.

The military chariots of the Philistines are similar to those of the Egyptians (see illustrations to “How Inferior Israelite Forces Conquered Fortified Canaanite Cities,” BAR 08:02). Both have six-spoked wheels and are drawn by two horses. The Philistine chariots functioned as mobile infantry units; the charioteers engaged in hand-to-hand combat after the initial chariot charge had stunned the enemy.

The Philistine infantry is shown fighting in small phalanges of four men each; three men are each armed with a long, straight sword and a pair of spears, the fourth with only a sword. All carry round shields and wear plain upper garments—possibly plain breastplates.

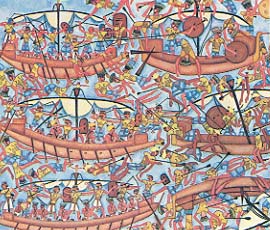

The Sea Peoples and the Egyptians fought not only in a land battle but also in a great naval battle which took place at the entrance to Egypt itself, possibly in the Nile Delta. The few ships depicted in the Medinet Habu reliefs are no doubt meant to represent a larger fleet. Four Egyptian warships engage five of the Sea Peoples’ vessels. The sea battle is another version of the land battle to the extent that grappling hooks were used to pull enemy ships together so that hand-to-hand fighting could ensue on deck.

The Philistine and Egyptian ships have many features in common: furled sails, a single mast with a crow’s nest, and identical rigging. The main difference between the ships of the Egyptians and the Philistines is that the latter are shown without oars (except for oars used as rudders). The figureheads are also different. The Philistine ships have birds’ heads at prow and stern; each Egyptian ship has a lioness’s head with a figure symbolizing Asia in her jaw at the prow and a plain, undecorated stern.

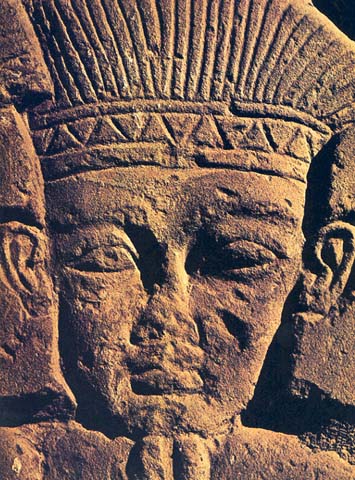

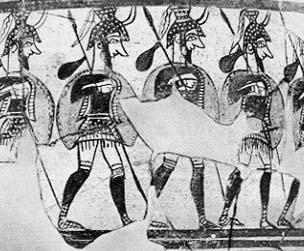

The battle headdress of the Sea Peoples clearly distinguishes the different groups. The Sherden wear horned helmets, the Teresh and Shekelesh have fillet headbands. The Philistines, the Tjekker, and the Denyen wear the so-called “feather” headdress, a leather cap and an ornamental headband from which a row of slightly curving strips stands upright to form a kind of diadem. Regardless of whether the strips are feathers, reeds, leather strips, horsehair, or some bizarre hairdo, this headgear is the distinguishing mark of the group dominated by the Philistines. We shall encounter it again in archaeological finds from Canaan.

The Philistines are also distinguishable by their dress. Each wears a short paneled kilt with wide hem and tassles. Above the waist is a ribbed corselet over a shirt. The thin strips of the corselet (made of leather or metal) are jointed in the middle of the chest and curve up. (On Sherden warriors, these strips curve down.) Perhaps these strips are meant to simulate human ribs. Similar corselets are known from Cyprus during this period and somewhat earlier; they indicate the Aegean background of the Sea Peoples. The corseleted Sea Peoples carry small round shields, easily distinguishable from the rectangular Egyptian shields.

Despite the massive forces of the Sea Peoples and their two-pronged land and naval approach, Ramesses successfully thwarted their attempt to overwhelm Palestine and the Egyptian Delta, as this passage from the Harris Papyrusa demonstrates:

“I [Ramesses III] extended all the frontiers of Egypt and overthrew those who had attacked them from their lands. … I settled them in strongholds, bound in my name. Their military classes were as numerous as hundred thousands. I assigned portions for them all with clothing and provisions from the treasuries and granaries every year.”

The resettlement program of Ramesses III is confirmed by the Onomasticon of Amenope,b (end of the 12th or beginning of the 11th century B.C.) which mentions those areas settled by the Sea Peoples in Canaan that were within the sphere of Egyptian influence. The three Sea Peoples included are the Philistines, the Tjekker and the Sherden. Ashkelon, Ashdod, and Gaza are listed as cities situated in the territory controlled by the Philistines. The emphasis Amenope gives to these three Philistine cities suggests that this territory still served as an Egyptian line of defense, and that the Philistines at this time were still, at least nominally, under Egyptian rule.

The famous Wenamun tale,c (middle of the 11th century B.C.) contains the sole reference to the area occupied by the Sea People known as the Tjekker. From this surviving story, we know the Tjekker occupied Dor. Wenamun, the author of the story, was a priest of the temple of Amun at Karnak who was sent to Byblos to buy cedar logs for the construction of Amun’s ceremonial barge. Wenamun’s misadventures and occasional humiliations by such characters as Beder, prince of the Tjekker town of Dor, indicate that Egypt’s hold on its Asian empire was already seriously weakened.

The Biblical references to Philistine origins are few and sometimes unclear. The earliest appears in the Table of Nations or “Generations of the Sons of Noah” in Genesis 10:14. The probable meaning of this verse, insofar as it relates to the Philistines, is “and the Caphtorim, out of whom came the Philistines.” According to this passage, the Caphtorim (and thus the Philistines) came from Egypt (Genesis 10:13). This may reflect the fact that the Philistines and other Sea Peoples were first settled in Egypt after their defeat by Ramesses III and then served as mercenaries in the Egyptian army. The homeland of the Philistines, Caphtor (Amos 9:7), is generally recognized by scholars as Crete, (although some believe Caphtor to be located in Cilicia in Asia Minor.)

In other Biblical references, the Philistines are synonymous with the Cherethites; that is Cretans (see Zephaniah 2:5 and Ezekiel 25:16). Various Biblical traditions suggest that the Caphtorim (or at least some of them) are to be identified with the Cherethites. Thus the Biblical sources seem to link the Philistines with a previous home in Crete.

The Bible also gives us historical references to the Philistine settlement in Canaan, beginning with the book of Judges. These references are far more explicit than those in Genesis, Zephaniah and Ezekiel previously mentioned. The well-known Samson cycle (Judges 13–16) must be understood against the background of a territorial conflict between the Philistines and the Israelite tribes of Dan and Judah. Samson’s tribe, Dan, was fighting for its very existence in the territory allotted to it on the eastern border of Philistia. Ultimately, the tribe of Dan was unsuccessful in this struggle, and by the end of the period of the Judges, was forced to abandon its inheritance and move to the Northern Galilee. The major conflict at this time was not between Dan and the Philistines but between the Philistines and the tribe of Judah. Judah was forced by Philistine pressure to occupy an area much smaller than that allotted to it. Open warfare between the Philistines and Judah began with the battle of Ebenezer (1 Samuel 4). The Israelites were thoroughly routed. The Philistines even captured the Ark of the Lord which the Israelites had brought to the battlefield in a vain effort to stave off defeat. The Philistines followed up on their victory by advancing all the way to Shiloh, where the ark had been kept in a tent-shrine. The Philistines apparently destroyed Shiloh (see Jeremiah 7:12–14; Psalms 78:60), and then continued northward on the Via Maris to capture Megiddo and Beth Shean. This gave them control of most of the territory west of the Jordan River; With these victories and with their monopoly on metalworking in the area (see Yohanan Aharoni, “The Israelite Occupation of Canaan,” BAR 08:03), the Philistines were able to keep the Israelites in a position of economic as well as political dependence.

Philistine dominance lasted for several generations, reaching its zenith during the second half of the 11th century. Despite their victories in the Jezreel Valley and at Beth Shean, the Philistines never enjoyed complete control over this territory for any extended period of time. For the most part, the Philistines occupied the territory in southern Palestine described in Joshua 13 as belonging to them at the death of Joshua, plus the coastal region extending north to the Yarkon River (near Tel Aviv) and east to the slopes of the Judean Hills.

The decisive clash between Israel and the Philistines took place soon after Saul was anointed king of Israel. Indeed, the primary motive for the creation of the Israelite kingdom was the Israelites’ desire to free themselves from Philistine domination. For this purpose, Saul organized a regular army. With this army, Jonathan assaulted the Philistines at Michmas (1 Samuel 13–14). The tide had turned in favor of the Israelites.

One of the best-known encounters between the Israelites and the Philistines was the contest between the respective champions David and Goliath. After David slew Goliath in the Elah Valley, the Philistines were pursued “even unto Gath and unto Ekron” (1 Samuel 17:52).

The successful advances of Israelite forces under King Saul soon ended, however. On the slopes of Mt. Gilboa, in a battle with Philistines forces, Saul and three of his sons were killed (1 Samuel 31). When the Philistines found Saul lying among the dead, they cut off his head and hung his body, stripped of its armor, from the walls of Beth Shean.

Following up on their victory, the Philistines captured and briefly held Canaanite cities in the Jezreel Valley including Megiddo.

After David’s victory over Goliath, he fled from Saul to escape Saul’s jealous wrath. David actually entered the service of the Philistine king of Gath, one Achish. David served Achish as a mercenary commander and later served as the vassal king of Judah (1 Samuel 21). About ten years later, David established his rule over the United Monarchy, and he “ … smote the Philistines, and subdued them, and took Gath and her towns out of the hand of the Philistines” (1 Chronicles 18:1). Consolidating his victories, David conquered the northern Shephelah and the coastal plain (formerly the tribal portion of Dan), including Dor, the Jezreel Valley, and finally the Beth Shean Valley. Thus, he greatly reduced Philistine territory; he may even have turned some Philistine cities into Israelite vassal states.

The famous Philistine Pentapolis consisted of the following major cities: Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Gath, and Ekron. Gaza appears in the Samson cycle (Judges 16) as the principal Philistine center, where the seranim (Philistine lords) gathered for festivals and sacrifices in the Temple of Dagon.

Ashkelon was also an important city-state and was known for its seaport. It is mentioned in the Samson cycle (for example, Judges 14:19), although less often than Gaza. A later reference to the “markets of Ashkelon” (2 Samuel 1:20) attests to that city’s status as an important mercantile center.

Ashkelon’s neighbor to the north was Ashdod, mentioned in the Bible chiefly in the account of the capture of the Ark of the Lord at the battle of Ebenezer. The Philistines took the Ark all the way to Ashdod, evidence that by about 1050 B.C. Ashdod was a major Philistine city-state. According to 1 Samuel 5, one of the two temples of Dagon was at Ashdod.

Considerably less is known about Gath, which may be located at Tell es-Sag. Gath’s strength and importance are attested by David’s vassalage to Achish, the king of Gath. Ekron was the northernmost of the Philistine cities, and controlled the territory allotted to the tribe of Dan. New excavations, begun at Tel Miqneh in 1981, already suggest that this may have been the site of Ekron. An interesting detail about Ekron is preserved in 1 Samuel 17:52; the men of Israel and Judah pursued the fleeing Philistines “to the gates of Ekron.”

In addition to the Pentapolis, two lesser Philistine cities, Ziklag and Timna, are mentioned in the Bible (1 Samuel 27:5). Like the smaller settlements of the Israelite tribes, these smaller Philistine cities are called haserim (villages) or banoth (daughters) in the Bible.

The government of the Philistine Pentapolis is, at best, adumbrated in the Bible. At the head of each Philistine kingdom (city-state) stood the seren (1 Samuel 5:8; 6:4, 16) a word that seems to be linguistically related to the Greek, tyrannos (tyrant). The Philistine ruler may also have borne the title “king,” as did King Achish of Gath (1 Samuel 21:11; 27:2). The limitation on the seren’s power is reflected in a disagreement between the Philistine princes (sarim) and Achish: Could David (who was then fighting for Achish) take part in the battle against Saul at Gilboa? (1 Samuel 29:4–10) Because of the princes’ objection to Oavid’s participation in the battle, Achish, despite his own judgment to the contrary, ordered David to remain behind while the Philistines went off to battle. The Philistine rulers obviously did not have absolute power over major political or military decisions.

The seranim led the armies that were vital to control the large civilian population. Each seren commanded his own army, assisted by sarim who undoubtedly held positions of high military rank. These armies included infantry, archers (see 1 Samuel 31:3), chariotry, and horsemen (1 Samuel 13).

The detailed Biblical account of Goliath’s armor and weaponry is a vivid description of a Philistine warrior in full battle dress:

“And he had a helmet of brass upon his head, and he was armed with a coat of mail. … And he had greaves of brass upon his legs, and a target of brass between his shoulders. And the staff of his spear was like a weaver’s beam, and his spear’s head weighed six hundred shekels of iron; and one bearing a shield went before him.”

(1 Samuel 17:5–7)

Goliath’s dress and armour (bronze helmet, coat of mail, bronze greaves [leg guards], and javelin) as well as the duel between champions are all well-known features of Aegean arms and warfare. They clearly indicate Aegean traditions carried on by the Philistines. The 12th century Warriors’ Vase from Mycenae shows Mycenaean warriors very similarly equipped.

Philistine religious organization and beliefs, as reflected in the Bible, suggest that by the 11th century the Philistines had already assimilated the main elements of Semitic Canaanite beliefs into their own religion. Biblical evidence gives no trace of a non-Semitic tradition, except the absence of circumcision. Apparently, the Philistines, alone among the peoples in Palestine during this period, did not practice circumcision (see 1 Samuel 18:25; Judges 14:3; and 1 Samuel 17:26, 36). The term “uncircumcised” by itself was sometimes used to refer to the Philistines (Judges 15:18; 1 Samuel 14:6; 31:4), indicating that all other peoples in the area (e.g. Israelites, Canaanites) must have been circumcised.

The head of the Philistine pantheon appears to have been the Canaanite god, Dagon (or Dagan) (1 Chronicles 10:10), to whom the temples of Gaza and Ashdod, and possibly one at Beth Shean, were dedicated. Another god, Baal-zebub (Baal-Zebul), had his oracular temple in Ekron. The goddess Ashtoreth, or Ashtaroth, apparently also had a temple at Beth Shean (1 Samuel 31:8–13). Philistine priests are mentioned only once in the Bible, when the Ark of the Lord is placed in the Temple of Dagon at Ashdod (1 Samuel 5). One of the few specifically Philistine religious beliefs in the Bible is the guilt offering (asham) sent to the Lord when the Ark was returned. The guilt offering was golden mice and golden tumors or boils (1 Samuel 6:4).

There is both agreement and discrepancy between the Biblical references to the Philistines and the archaeological evidence. The Aegean background of Philistine religion (which is not disclosed in the Bible) is especially evident in the earliest examples of cult objects from Ashdod (from the 12th century B.C.) which emphasize the worship of the Mycenaean “Great Mother” or “Great Goddess.” Archaeological evidence from the Aegean has revealed that in that area, female, not male, deities were predominantly worshipped. Apparently by the 11th century this pantheon was replaced by a male Canaanite pantheon reflecting the Philistines’ more recent cultural milieu.

The sites containing Philistine cultural remains are found principally in the Shephelah and the southern coastal plain, but there is also evidence that Philistine culture spread to a variety of sites in other areas of the country. Major excavations have established a clear stratigraphic sequence through which we can trace the initial appearance, then the flourishing, and finally the subsequent assimilation of Philistine material culture, a process which spanned the period from about 1200 B.C. to 1000 B.C. (When I refer to Philistine material culture I include all Sea Peoples whose cultural backgrounds were similar.)

Of the five Pentapolis sites, only three—Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod—have been definitely located, and only one, Ashdod, has been thoroughly excavated. At Gaza, only the slightest evidence attesting a late Philistine occupation has been uncovered. The limited archaeological work at Ashkelon has revealed that the last Canaanite stratum suffered a violent destruction and was followed by a Philistine settlement. Khirbet Muqanna (Tel Miqneh) may be the site of Ekron, an identification that has been strengthened by our recent excavations there. The location of Gath is still an open question: the most likely site is Tell es-Sefi. The most extensive evidence of Philistine material culture has come from recent excavations at Tell Ashdod and from a site on the northern border of Philistia whose ancient name we do not know—Tell Qasile within the city limits of modern Tel Aviv. These two sites, Tell Ashdod and Tell Qasile provide complementary data on the nature of Philistine urban settlement, facets of their material culture, and cultic structures and practices.

Strata XIII through X at Ashdod tell the story of the Philistines’ occupation there. The first sign of the new population’s arrival is dramatic: the Egyptian-Canaanite fortress (stratum XIV, Area G) was partially destroyed and an open-air cult installation was built over it (stratum XIII). Adjacent to this installation was a potter’s workshop housing a rich collection of locally made Mycenaean III C:1 pottery. This pottery, originally Aegean in style, seems to be a precursor of the earliest Philistine ware. These monochrome Mycenaean III C:1 pottery sherds appeared just before the colorful Philistine ware and continued to be produced along with the Philistine pottery, indicating perhaps that an earlier wave of Sea Peoples had preceded the great invasion described in the Medinet Habu inscription in the first half of the 12th century B.C. Mycenaean III C:1 ware has very recently been found in large quantities at Tel Miqneh (Ekron) and indicates that the same settlement pattern is evident in this Philistine city.

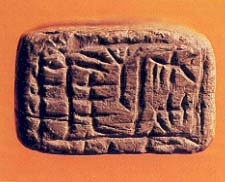

After stratum XIII, a thriving fortified Philistine city was found at Ashdod in strata XII through XI. The small finds include a gold disc and seals inscribed in a still undeciphered script. These may be our only examples of Philistine language and writing. Until more samples of this script are found, however, we must be cautious about its identification, but it may have Aegean affiliations.

The Philistine city at Ashdod was well-planned; the archaeologists uncovered two building complexes carefully divided by a street. The northern complex consisted of an apsidal structure with a courtyard and adjacent rooms. Here the earliest known Philistine cult deity, nicknamed “Ashdoda,” was found. It is a figurine whose prototypes seem to be the figurines of the Mycenaean “Great Mother.” Elsewhere at Ashdod, excavators uncovered a cultic stand decorated with musicians. A similar cultic stand was found at Tell Qasile.

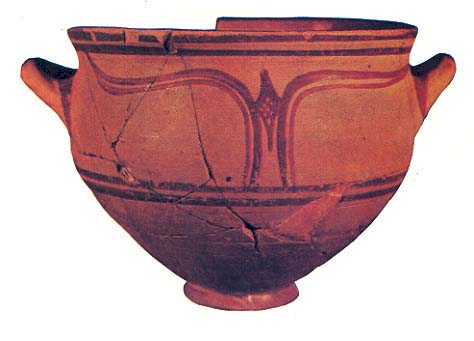

Stratum X (c. 1050 B.C.), represents the last, largest and most prosperous Philistine city at Ashdod. At that time a Lower City outside the acropolis area was occupied for the first time. Massive brick walls and a very strong gate were built to protect this enlarged city. Ironically enough, although the Philistine population had grown and flourished, its culture, as evidenced by its pottery, had not. The pottery reflects assimilation into the local pottery repertoire and some types disappear altogether. New hybrid forms are created. For example, at Ashdod, black on red decoration shows affiliations with the Phoenician culture, while at Tell Qasile, a new krater form was created through the fusion of old and new, local and foreign features coming together. Ceramic features which usher in the ceramic style of the Iron Age are its red slip and burnishing. Eventually pottery and all other evidence of Philistines totally disappeared from higher strata at the site.

The city at Tell Qasile was founded by the Philistines in the first half of the 12th century B.C. on the northern bank of the Yarkon River. The site was obviously chosen because it was a perfect inland port site. Tell Qasile was established on virgin soil to suit particular socio-economic needs. The town was well-planned, with separate residential, industrial, and sacred quarters.

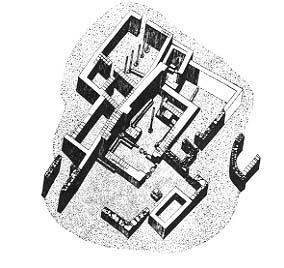

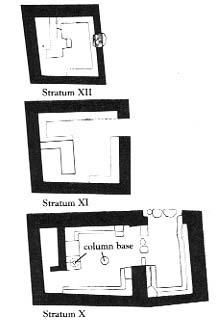

Three superimposed temples were uncovered in the northeast part of the tell, the first well-defined Philistine temples ever discovered. This area was evidently the cultic center of the Philistine city. In each of the three strata, XII through X, a new temple was constructed, each larger than the last. The earliest temple (stratum XIIa) was a one-room mud-brick structure.

The stratum XI temple was larger than its predecessor, but still consisted of a single room, the cella. The stratum XI temple had a plastered floor and brick benches along the wall. The stratum X temple was evidently merely an enlargement and rebuilding of the stratum XI temple on a different plan. The stratum X temple (the latest) consisted of two main rooms—the main hall and an antechamber.

The altar was located directly opposite the central opening of the main hall so that the visitor had an unobstructed view from the entrance. No exact parallels have been found in Canaan. Many features continue the Canaanite tradition but other features incorporate Aegean characteristics. The Tell Qasile temple is similar to the 13th–12th century temples at Kition, Cyprus, and to recently discovered shrines at Mycenae, mainland Greece, and Phylakopy on the island of Melos. This again indicates the clear connection between the Aegean and Philistine cultures.

In the open courtyard west of the Tell Qasile temple, excavators found a pit, or favissa, containing a buried cache of cult vessels used in the stratum XI temple. Among the finds were a lion-head rhyton and a female figure vessel. Perhaps this female figure was the goddess of the temple.

In other quarters of the city at Tell Qasile, residential and industrial structures were uncovered. The flourishing city in stratum X had well-planned houses with courtyards. The furnishings found in these houses are illuminating clues to the daily life of the Philistines at a time when they were not only prosperous but when they had already assimilated local Canaanite culture. Their success is reflected in the grain pits, silos, presses, and storerooms, and in the store jars for wine and oil, as well as in the great number of farm tools, including flint sickle-blades. The archaeological finds include remains of a metal industry and several work shops.

No archaeological study of the Philistines would be complete without considering their connection with the new metal of the era, iron. The Bible (1 Samuel 13:19; 17:7) offers only tantalizing hints that the Philistines attempted to maintain a technological superiority over the Israelites in the production and distribution of metals, perhaps including iron. This suggestion is supported by the fact that most of the iron tools and weapons found in Israel before about 1000 B.C. come from sites that show signs of Philistine occupation or influence—for example, the iron knives from Tell Qasile and from the Tell el-Far’ah (South) Philistine tombs. However, the older view that the Philistine introduced iron production into Canaan has been challenged. Apparently, the political upheavals that characterized the late 13th century in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean disrupted trade in copper and tin, thus providing an incentive to develop other resources such as iron. It is true that only small quantities of iron have been found in Canaan dating to before the 12th century when the Philistines arrived in the area, but the gradual development of iron technology under a variety of influences, including that of the Philistines, is a complex story. Moreover, iron did not become common in Israel until after the eclipse of Philistine culture in the tenth and ninth centuries.

The Philistine material culture, particularly the pottery and cult vessels, does not accord with the negative meaning of the term “Philistine” as it is used today. Philistine ceramic ware demonstrates high artistic and aesthetic abilities. Indeed, Philistine material culture stands out against the bleak background of the world in which they lived.

Philistine pottery in the Holy Land is a large, homogenous group of locally made painted ware, derived from Mycenaean traditions in shape and decoration. We are able to connect this distinctive pottery with the Philistines for a variety of reasons, geographical, stratigraphical and comparative.

The geographical distribution of this pottery corresponds strikingly with the territory occupied and influenced by the Philistines, diminishing as one moves away from Philistia itself.

Stratigraphically, Philistine pottery occurs in levels and deposits which can be dated from the first decades of the 12th century to the late 11th century B.C., a time span closely corresponding to the Philistine settlement and expansion.

A comparative study of the various phases of Philistine pottery is of greatest assistance, however, in understanding the rise and fall of Philistine culture in Canaan. Initially, the pottery reflected the process of crystallization and diffusion of Philistine culture in Canaan. Then we see a gradual assimilation of local material culture. Eventually Philistine ware disappeared altogether.

The story begins with the appearance of a locally produced variant of monochrome Mycenaean III C:1 ware (reflecting Philistine origins) at a few sites, especially Ashdod and Tel Miqneh, around 1200 B.C. Not long after this, we find the first Philistine ware per se, with its rich variety of motifs in bichrome decoration of black and red on a heavy white slip background. In the last quarter of the 12th century, we already notice a slight decline in the overall quality of the ware and some departure from original Mycenaean shapes and decoration. Then in the second half of the 11th century, a steep decline set in, with some hybrid Philistine and local types appearing, while other Philistine forms slowly assimilated into local styles. This transformation can be seen particularly in the bowls and kraters. The white-slipped, bichrome decoration gradually died out, often replaced by the red slip, hand burnishing, and dark brown decoration more characteristic of Canaanite ware. Not long after 1000 B.C., when David humbled the once-powerful Philistine military machine, the distinctive features of Philistine pottery faded away completely.

The shapes and decorative motifs of Philistine pottery were a blend of four distinct ceramic styles: Mycenaean, Cypriot, Egyptian, and local Canaanite. The dominant traits in shape and almost all the decorative elements were derived from the Mycenaean repertoire, and, as we have said, point to the Aegean background of Philistine pottery Philistine shapes of Mycenaean origin include bell-shaped bowls, large kraters with elaborate decoration, stirrup jars for oils and unguents, and strainer-spout beer jugs; the latter no doubt served as centerpieces at many a Philistine party. A few of the many decorative motifs are stylized birds, spiral loops, concentric half-circles, and scale patterns. Although Philistine vessels were richly decorated with motifs taken from the Mycenaean repertoire, these motifs were rearranged and integrated with other influences to create the distinctive “signature” known as Philistine.

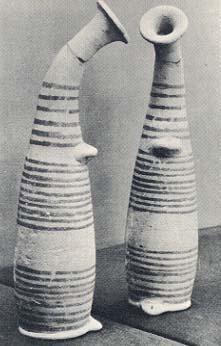

Cypriot influence in Philistine pottery is most striking in the bottle and the horn-shaped vessel. An elongated cylindrical body tapering to a narrow curved neck gives the horn-shaped vessel its name. Both Cypriot and Philistine examples represent cheaper copies of similar vessels made of ivory and alabaster, and appear during the Late Bronze Age (13th century B.C.) and continue through the Iron Age (early 12th century B.C.).

Egypt makes its most visible contribution to the Philistine repertoire with the tall-necked jug. The long, slightly bulging neck is a common feature of the Egyptian ceramic tradition. The stylized lotus motif which appears on Philistine pottery was taken directly from Egyptian prototypes. The tall-necked jug is not, however, exclusively of Egyptian inspiration; on the contrary, it is an outstanding example of the eclectic nature of Philistine pottery: It is Egyptian in the shape of the neck and in the neck decoration, Aegean in the decorative motifs on the main band of body decoration, and Canaanite in the shape of the body. All three elements are blended beautifully into a single pottery type. The role of Canaanite pottery in the Philistine repertoire is limited, but clear: the Philistine potter applied his own decorative motifs to long-established Canaanite pottery shapes.

The unique style of Philistine pottery is the result of the Philistine potter’s success in integrating ceramic traditions from his Aegean homeland with influences from the Cypriot, Egyptian, and local Canaanite pottery groups to which he was exposed.

Philistine cult vessels provide us with insights into Philistine ritual and beliefs. They also demonstrate how Philistine craftsmen wove their Aegean traditions with strands from Egypt and Canaan, as well as with their own ideas to create innovative and distinctive cult objects.

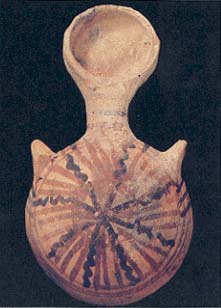

Take, for example, the kernos or pottery ring. The kernos form itself reflects Aegean influences. A kernos is a hollow pottery ring about 10 inches in diameter on which hollow objects like birds or pomegranates are set. We are not sure how it was used but probably a liquid of some kind was poured into the hollow ring, shaken about, and poured out in the course of a religious ritual. The well-known Gezer Cache included a Philistine kernos with an attached bird, a pomegranate, and bird vessel. But it also contained a faience fragment bearing the cartouche of Ramesses III, thus dating this cache to the first half of the 12th century B.C. The beautiful white-slipped, bichrome objects belong to the earliest phase of the Philistine style.

A distinctive Philistine cult vessel is the one-handled lion-head rhyton, a ritual or drinking cup; examples have been found at a variety of sites. The Philistine pottery rhyton is the last echo of a long Mycenaean-Minoan tradition of metal and stone animal-head rhyta. These vessels have been found in the shaft graves at Mycenae, at Knossos on Crete, and have been pictured on New Kingdom tomb walls in Egypt. From a later period (13th to early 12th century B.C.) comes an ivory plaque from the treasury at Megiddo on which are incised two rhyta, one lion-headed and the other gazelle-headed, carried by two servants in a procession (see photograph in “The Finds That Could Not Be,” BAR 08:01).

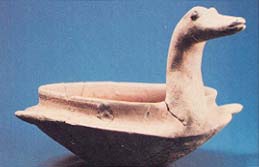

In the Philistine temple at Tell Qasile, three high cylindrical cult stands were found. Each had a bowl topped with a bird’s head. Although the bird representation has a long history and is well attested in the local Canaanite repertoire, its recurrence in different facets of Philistine culture is striking. Various types of terra-cotta vessels found at many Philistine sites are formed in the likeness of birds. Painted birds are a distinctive feature of Philistine pottery. The ships of the Sea Peoples depicted at Medinet Habu have bird figureheads. The motif is considered emblematic of Philistine decorative art.

Another cult stand, found at Ashdod, features five musicians around its base (see photograph in “The Finds That Could Not Be,” BAR 08:01). Four are modeled in the round and stand in windowlike openings. The fifth and central figure was formed by a combination of techniques. The figure’s outline was cut out, then the individual features were molded and added. Each of the figures in the Ashdod stand plays a musical instrument: cymbals, double pipe, frame drum, and stringed instrument that is probably a lyre. We are reminded of the passage from 1 Samuel 10: “After that thou shalt come to the hill of God, where is the garrison of the Philistines; and it shall come to pass when thou art come thither to the city, that thou shalt meet a company of prophets coming down from the high place with a nevel (large lyre) and a tof (frame drum) and a halil (double pipe) and a kinnor (lyre) before them: and they shall prophesy.” The musicians represented on the stand were probably part of a Philistine cult, their role similar to that of the “Levites which were singers” in the temple of Jerusalem (2 Chronicles 5:12–13).

Female pottery figurines also reflect Philistine cult origins and beliefs. The “Ashdoda” is the only complete example of a well-defined type that was common from the 12th to the eighth century B.C. The Ashdoda figure is probably a schematic representation of a female deity and throne. It is clearly related to a grouping known throughout the Greek mainland, Rhodes and Cyprus—a Mycenaean female figurine seated on a throne, sometimes holding a child. These Mycenaean figurines are thought to represent a mother goddess.

Hints of Philistine mourning customs can be gleaned from the terra-cotta female mourning figurines from Philistine contexts at sites such as Tell ‘Aitun and Azor. Most of this material comes from burials. These figurines stress hand gestures. Sometimes both hands hold the top of the head. On others, one hand is placed on the head and the other on the breast. Such figures are often attached to the rims of Philistine kraters. Similar mourning figures on similar kraters are closely associated with the burial customs and the cult of the dead found in the Aegean world at the end of the Mycenaean period. Here is another clear Aegean component of Philistine culture, this time in funerary rites.

Burial customs are generally a sensitive indicator of cultural affinities, and Philistine burial customs reflect the same fusion of Aegean background with Egyptian and local Canaanite elements that distinguishes every other aspect of their culture. As yet no burial grounds in any of the main Philistine cities, such as Ashdod, have been found; however, several cemeteries that can be related to Philistine culture on the basis of tomb contents have been explored. In some cases the Philistines perpetuated the indigenous funerary customs and tomb architecture; in others, they employed foreign modes of burial, such as the cremation interment found at Azor.

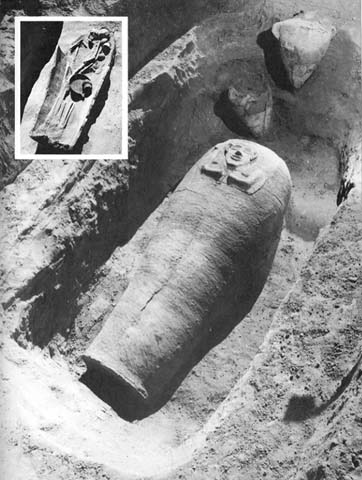

Two other features of Philistine burials are illuminating—the use of anthropoid clay coffins (an Egyptian custom) and interment in rock-cut chamber tombs whose design is Mycenaean in origin.

Anthropoid coffins are built roughly in the outline of a body; the lid is formed in the shape of a head. At Tell el Far‘ah in the Negev, Petrie found two complete anthropoid coffins in chamber tombs he called “the tombs of the lords of the Philistines.” These coffins were built up by the coil technique, which was often used in making large vessels. The lid was cut out of the leather-hard clay before firing so that it exactly fit the opening. The lids were ineptly modeled with faces in what has aptly been termed the “grotesque” style, with only a schematic outlining of facial features and arms. Although the anthropoid coffins were adopted by the Philistines directly from the Egyptians, their use among the Philistines did not become common. The tombs themselves consist of a stepped dromos (or passageway) leading to a rectangular chamber with shelves cut into the rock for placing the deceased and his or her burial goods. This tomb type was common throughout the area of Mycenaean influence.

At Beth Shean, about 50 anthropoid coffins were discovered in 11 funeral deposits in the Northern Cemetery, dating from the 13th to the 11th centuries B.C. Of this number, only five have lids and other features that link them to the “grotesque” style encountered at Tell el-Far’ah. The distinctive feature of the Beth Shean “grotesque” lids is the applique headdress, which consists of plain horizontal bands, rows of knobs, zigzag patterns, and vertical fluting. These patterns are arranged differently on each lid. However, one lid portrays a headdress crowned by vertical fluting, identical to the “feathered” cap worn by the Peleset (Philistines), Tjekker, and Denyen on the Medinet Habu reliefs of Ramesses III. This headgear provides decisive evidence that the bodies buried in the grotesque coffins at Beth Shean were Sea Peoples, quite possibly Philistines. The Bible (1 Samuel 31:8–13; 1 Chronicles 10:9–12) relates that Beth Shean was occupied by the Philistines after Saul’s defeat at Gilhoa in the late 11th century B.C. The grave goods associated with these “grotesque” headdress coffins at Beth Shean confirm a date in the second half of the 11th century, the time of Saul.

Although there is no doubt that Philistines used clay anthropoid coffins, the great majority of clay coffin burials discovered in Palestine belong to a period preceding the Philistines, when Egyptian officials and garrison troops were stationed in Egyptian strongholds. The Egyptian “middle class,” in Egypt as well as in Canaan, frequently used clay coffins, in which grave goods of Egyptian, Mycenaean, Cypriot and Canaanite origin were buried.

The Egyptian stronghold and associated cemetery discovered by the author at Deir el-Balah is typical of a period of Egyptian domination, followed by Egyptian-influenced Philistine occupation of the site. The cemetery yielded an outstanding assemblage of some 40 complete coffins as well as Egyptian faience, alabaster, and gold burial items. The cosmopolitan character of those buried at Deir el-Balah is evidenced by the collections of pottery grave goods of Egyptian, Canaanite and Aegean types, dating from the late 14th through the 13th centuries B.C. A Philistine settlement succeeded the Egyptian stronghold at Deir el Balah. Although no Philistine burials have yet been discovered, it seems likely that the Philistines at this site at least occasionally adopted the Egyptian practice of burial in a clay coffin, as they clearly did both at Tell el-Far’ah and at Beth Shean. Clay coffin burials are simply one more instance of the Philistines adopting and adapting Egyptian cultural traits after their mercenary service in or near Egyptian strongholds during the sunset of the Egyptian empire.

Thus, new discoveries in the Aegean and the Levant have transformed our view of the Philistines and have provided us with a detailed portrait of these Biblical people. We are now entering a new phase of research which may eventually allow us to distinguish the culture of the Philistines from other Sea Peoples. The new excavations at the Tjekker port of Dor, and the continuing work at Akko (possibly a Sherden site), may enable us to discover cultural distinctions between these two related peoples and the Philistines. While the search for the Philistines continues, the search for other Sea Peoples in Canaan has just begun.

Further Reading

Dothan, M., and Freedman, D. N. Ashdod I (Atiqot VII), Jerusalem, 1967.

Dothan, M. Ashdod II–III (Atiqot IX–X), Jerusalem, 1971.

Dothan, T. Excavation at the Cemetery of Deir el-Balah (QEDEM X), Jerusalem, 1979.

Dothan, T. The Philistines and Their Material Culture. New Haven, 1982.

Malamat, A. “The Struggle against the Philistines.” In The History of the Jewish People, edited by H. H. Ben-Sasson, pp. 80–87. Cambridge, Mass. 1976.

Mazar, A. Excavations at Tell Qasile (QEDEM XII), Jerusalem, 1980.

Mazar, B. “The Philistines and Their Wars with Israel.” In The World History of Jewish People, Vol. 3, Judges, edited by B. Mazar, pp. 164–179. New Brunswick, 1971.

Sandars, N. K. The Sea Peoples: Warriors of the Ancient Mediterranean. London, 1978.

The author and the editors wish to acknowledge the valuable assistance of Jehon Grist in the preparation of this article.

This article, written especially for Biblical Archaeology Review, is based on materials contained in Professor Trude Dothan’s recently published book, The Philistines and Their Material Culture (Yale University Press, 1982). For a review of this book, see Books in Brief.