Christian Pilgrimages

Generations after the reign of Constantine the Great, the first Christian Roman emperor, the Byzantine phenomenon of traveling to sites associated with Jesus, his apostles and Christian saints and martyrs grew into a popular practice. Followers traveled in increasing numbers from all over the Mediterranean to visit sites where major Biblical events were purported to have occurred and to witness holy relics. While many sites were located in Byzantine Palestine, pilgrims also ventured to Asia Minor, Egypt, Greece and Syria. Popular travel destinations included places associated with the life, miracles and passion of Jesus. The Byzantine practice of Christian-motivated travel was disrupted in the first half of the seventh century with the Arab conquest of the eastern Mediterranean.

What can holy sites, relics and contemporaneous travelogues tell us about the early Christian pilgrim experience? Find out in this BAS Library Special Collection.

Scroll down to read a summary of these articles.

The Holy Land in Christian Imagination

Bible Review, Apr 1993

by Robert L. Wilken

A Pilgrimage to the Site of the Swine Miracle

BAR, Mar/Apr 1989

by Vassilios Tzaferis

The True Cross

Bible Review, Aug 2003

by Jan Willem Drijvers

Don’t Leave Home Without Them

BAR, Jul/Aug 1997

by Gary Vikan

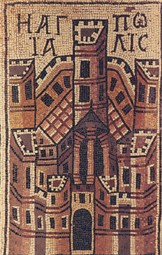

How did the concept of the Holy Land develop? In “The Holy Land in Christian Imagination,” Robert L. Wilken describes how the idea of the Biblical Holy Land was first rooted in the Jewish hope to repossess the land of Canaan after centuries of exile, displacement and destruction. Having grown out of Judaism, Christianity was from its beginnings a faith centered on the events that occurred in Jerusalem and other parts of Israel. It was not until the sixth century that the term “Holy Land” was used by Christians to designate the places where Biblical history occurred. By this time, thousands of pilgrims were coming from all over the Mediterranean to Israel to visit the churches, shrines and memorials commemorating the Christian faith.

From the earliest periods in which Christians made pilgrimages, the area around the Sea of Galilee was a major destination second only to Jerusalem. Sites situated in the region recalled the places where Jesus taught and performed miracles. One such pilgrimage site, presented by excavator Vassilios Tzaferis in “A Pilgrimage to the Site of the Swine Miracle,” was thought to be the place where Jesus cured a demoniac by casting the demons out of him and onto a nearby herd of swine. Located in the Valley of Kursi, the site of the so-called swine miracle was sanctified in the late fifth or early sixth century with a large monastery and a memorial tower and chapel. Here, pilgrims could pray and reflect on the life and miracles performed by Jesus.

Early Christian pilgrims not only sought to visit sites where Biblical events occurred, they were motivated to travel long distances in order to see objects associated with Jesus and his notable followers. In the fourth century, Emperor Constantine’s mother Helena was said to have “rediscovered” the wooden cross on which Jesus died in Jerusalem. But did Empress Helena actually find the true cross? In “The True Cross,” Jan Willem Drijvers explores the story behind the pilgrimage and the discovery of arguably the most important relic in the Christian faith. If Helena did not discover the true cross, who created this legend, and what purpose did it serve?

For the Byzantine traveler, bandits, wild animals and hostile local populations threatened overland travel, while storms, harsh climates and crude harbors threatened sea travel. What did travelers do for travel insurance? In “Don’t Leave Home Without Them,” Gary Vikan describes how Christian pilgrims protected themselves against these threats: They carried blessed amulets, including tokens and flasks, as supernatural guardians. Called eulogiai (“blessings”), these amulets depicted Christian saints, symbols and holy events appropriate for warding off the dangers of travel. Byzantine pilgrimage iconography developed from these amuletic objects, forming a type of traveler’s art that was disseminated throughout the eastern Mediterranean.