Writing and Literacy in the Biblical World

Reading and writing are integral parts of our everyday lives, but this was not true for everyone in the Biblical era. How did the alphabet develop in the Holy Land, and who could read it? Inscriptions teach us about the culture, economy and literary traditions of the ancient occupants of archaeological sites. What role did texts play in their contemporaneous societies? Who could read them? What is the likelihood that eyewitness records of Jesus’ deeds could have been recorded? Biblical Archaeology Society editors have arranged a special collection of articles from the BAS Library exploring writing and literacy in the Biblical world, from Early Bronze Age Canaanites to the authors of the New Testament.

Scroll down to read a summary of these articles.

How the Alphabet Was Born from Hieroglyphs

BAR, Mar/Apr 2010

by Orly Goldwasser

The Evolution of Two Hebrew Scripts

BAR, May/June 1979

by Jonathan P. Siegel

What’s the Oldest Hebrew Inscription?

BAR, May/June 2012

by Christopher A. Rollston

Literacy in the Time of Jesus: Could His Words Have Been Recorded in His Lifetime?

BAR, Jul/Aug 2003

by Alan Millard

Biblical Views: Sacred Texts in an Oral Culture: How Did They Function?

BAR, Nov/Dec 2007

by Ben Witherington III

More than 3,800 years ago, illiterate Canaanite laborers working in the turquoise mines of Sinai were responsible for one of the most significant inventions in human history: the alphabet. In “How the Alphabet Was Born from Hieroglyphs,” Egyptologist and hieroglyph expert Orly Goldwasser explores the simple but ingenious ideas that led these miners under hieroglyphic inspiration to create the first-ever alphabetic script. Goldwasser’s inspired interpretations earned this article the “Best of BAR” award for 2009–2010.

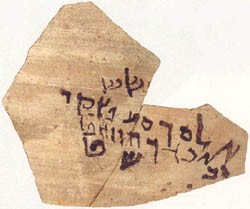

Until the First Temple was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 B.C., the paleo-Hebrew script, which differs radically from the modern Hebrew alphabet, was the only alphabet used by the Israelites. When the Judean exiles returned from Babylon, they brought back with them a new language—Aramaic—and a new script—the square Aramaic script. Ultimately, the Aramaic script replaced the older paleo-Hebrew script, but for hundreds of years the two scripts were used simultaneously by the Jews. In “The Evolution of Two Hebrew Scripts,” Jonathan P. Siegel guides readers through the histories of the scripts, using important documents including the Izbet Sartah abecedary, Jewish coins, the Bar-Kokhba Letters and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

“What’s the Oldest Hebrew Inscription?” Weighing in on a quartet of contenders for the oldest Hebrew inscription, epigrapher Christopher A. Rollston explains how he decides: Is the script really Hebrew? Is the language Hebrew? Should the inscription be read right-to-left like modern Hebrew or left-to-right? How old is it? Where did it come from? Readers may be surprised by his conclusions.

Archaeologists have uncovered numerous inscriptions that provide invaluable insights into the Biblical world, but could they be understood by contemporaneous people? And could average people keep these records, or was that privilege reserved for the temple elite? In “Literacy in the Time of Jesus,” Alan Millard explores the question: Could the words of Jesus have been recorded in his lifetime? Archaeological discoveries and other lines of evidence now show that writing and reading were widely practiced in the Palestine of Jesus’ day. And if that is true, there is no reason to doubt that there were some eyewitness records of what Jesus said and did.

It is difficult for us, in a text-based culture, to conceive of and understand an oral culture, much less how sacred texts function in such a culture. It is nevertheless important that we try to understand oral culture, since all the cultures of the Bible were essentially oral cultures. In the Biblical Views column “Sacred Texts in an Oral Culture: How Did They Function?” Ben Witherington III explores the power of words at the start of Christianity, and reveals that texts that ultimately became part of the New Testament were treasured during the first century and were lovingly and carefully copied for centuries thereafter.