How to Read Etruscan

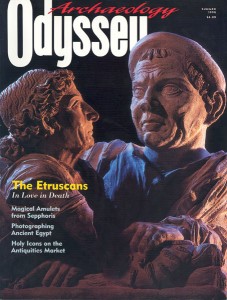

Sidebar to: The Etruscans

Etruscan writing has the reputation of being elusive. It attracts amateur sleuths from around the world hoping to decipher the texts. But Etruscan is not mysterious or in need of decipherment. The texts can be read; they always could be read because the Etruscan alphabetic script is derived from a West Greek model.

The problem is that we do not know much about how the Etruscan language works. This is primarily because there are no well-understood related languages with which Etruscan can be compared to help us to determine word meanings and syntactic features.

There are approximately 9,000 Etruscan inscriptions, mostly from Etruria. Others have been found in Latium and in Campania in southern Italy. A handful have been discovered at sites scattered throughout the Mediterranean. The inscriptions cover a chronological span of 750 years—from the end of the eighth century B.C.E. to the middle of the first century C.E., when Etruscan ceased to be spoken as a native language. Epitaphs on sarcophagi, cinerary urns, funerary stelae and the walls of tombs make up about 90 percent of the corpus. Other inscriptions—signatures of artisans, votive dedications and ownership labels—are found on pottery.

The most important and longest Etruscan text (about 1,200 words) is the Liber Linteus, now in the National Museum in Zagreb, Croatia. This text was written on linen; it was preserved only because it was transported to Egypt and used to bind a mummy. A ritual calendar, the Liber Linteus specifies the dates and features of important Etruscan religious festivals as well as prayers and rituals performed at them.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address.