In June of 313 C.E., while languishing on China’s northwest frontier some 2,000 miles east of his native Samarkand, a merchant named Nanai-vandak wrote a poignant letter to his business associates back home: A severe famine in the Chinese capital, Luoyang, had led to the death of some of his compatriots. Fearing that he too might perish, Nanai-vandak asked his friends to invest his savings on behalf of his “orphan” son back home.

Sadly, this letter never reached its destination. In 1907 the British archaeological explorer Aurel Stein found it with several other letters near Dunhuang, a guard post at the western end of China’s Great Wall. The letter had probably been lost in transit or confiscated by Chinese authorities.

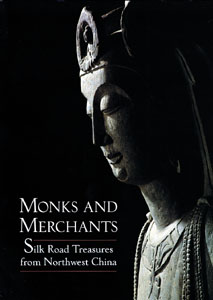

Nanai-vandak’s letter was one of more than a hundred rare Chinese artifacts included in a 2001 exhibition on the Silk Road organized by the Asia Society Museum in New York. The exhibition’s beautifully illustrated catalogue, Monks and Merchants: Silk Road Treasures from Northwest China, shows that the Silk Road, which stretched from the eastern Mediterranean to China, was much more than a trade route: It was an extraordinary conduit for the transmission of ideas, artistic techniques, cultural traditions and religious beliefs.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address.