Ancient Life: Sustaining Ka

The Longest Journey

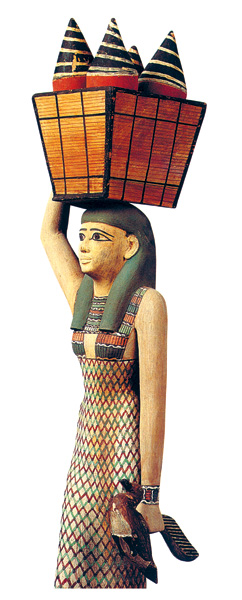

Balancing a wicker basket on her head, this 4,000-year-old wooden statue of a female offering bearer was discovered at Thebes, Egypt, in the tomb of a man named Meketra, an official of the 11th Dynasty (2134-2040 B.C.).

The 4-foot-high, vividly painted statue was one of 25 similar wooden carvings recovered from the tomb. Our maiden carries four wine jars topped with conical lids and a live goose—sustenance for Meketra in the afterlife.

During the early Egyptian dynasties, only deceased pharaohs and their intimates were thought to live on in the next world. Their bodies were mummified and their tombs lavishly furnished with real and symbolic weapons, food, jewelry, toiletries, games and furniture. By the time of Meketra, however, lesser nobles assumed that they were eligible to enter the afterlife.

The deceased’s family was responsible not only for stocking their loved one’s tomb but also for keeping the offerings coming over time. Some families paid priests to pour beer or wine on a carved stone table within the tomb’s chapel or to leave food offerings on a woven reed mat placed at the tomb’s entrance. Other common perishable offerings included beef, fowl, grapes, pomegranates and bread. There were also symbolic ways to nourish the deceased’s ka, or soul: Offering prayers were recited for the dead, and tomb interiors were often carved or painted with scenes of feasts.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address.