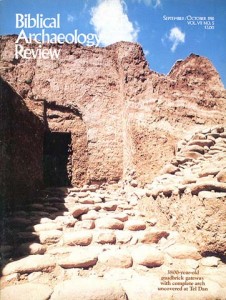

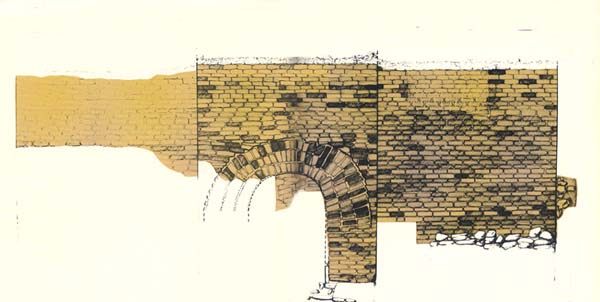

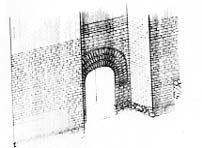

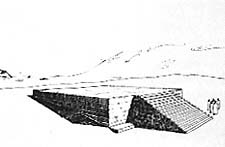

In the summer of 1979 an astounding structure was uncovered at Tel Dan in northern Israel. Excavators from the Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion expedition found a huge mudbrick gateway consisting of two towers joined by a completely intact mudbrick arch. The complex is dated to the Middle Bronze II A-B period, about 1900–1700 B.C. The exact date is not yet known but it is probably earlier than 1700 B.C.

That the mudbrick towers were preserved to a height of almost 20 feet (very nearly their original height) was amazing enough. That the three courses of the mudbrick arch connecting these towers survived complete and undamaged after 3,800 years seemed almost miraculous.

This is the only existing structure of its kind in the entire Near East. Remains of Middle Bronze gates have been found at Hazor, Megiddo, Shechem, Gezer and even Troy—but none of them is preserved intact. To find an entire mudbrick structure as old as the gate at Dan in this unbelievable state of preservation is hardly dreamed of by archaeologists.

The arched mudbrick gateway, built more than 700 years before the tribe of Dan captured the city, was preserved only because—for reasons not yet completely clear—it was buried. Whether the arched gateway can be preserved now that it is exposed to the air and the weather is a troubling question.

No one was more surprised at the discovery of the gateway than Avraham Biran, head of Hebrew Union College’s Nelson Glueck School of Archaeology and former Director of the Israeli Department of Antiquities. Biran has been director of excavations at Tel Dan since 1966.

How the gateway itself happened to be discovered at Tel Dan is a story in itself.

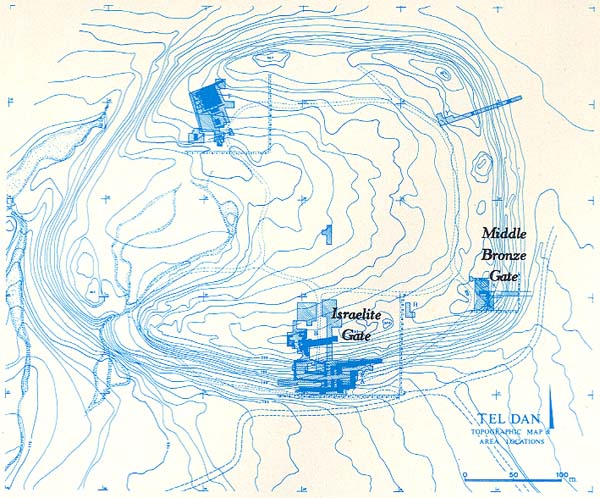

One of the most formidable features of Tel Dan—a 50-acre mound—is a massive rampart that surrounds most of the tel. Biran has expended enormous effort over the years trying to understand this rampart. Massive ramparts are common features surrounding Palestinian cities in the Middle Bronze Age. The rampart at Dan—or Laish, as it was then called—was by no means unique. It is generally thought that these ramparts were a defensive response to the invention of the battering ram. However, this is a much-disputed question; eminent archaeologists are still in disagreement as to just why these ramparts were built.

By 1978, Biran had cut through the Dan rampart at two places in order to examine its construction. From these two cuts, one in Area A at the southern end of the mound and the other Area Y at the northeastern end of the mound, Biran learned that the rampart consisted of an inner stone core which supported the outer slope on either side of the core. The earthworks thrown up against the stone core on the outside of the rampart consisted of alluvial soil from the surrounding plain. On the inside of the rampart, the builders built up against the stone core with soil from inside the city which included occupational debris from earlier periods. The base of the completed rampart, from one side to the other with the stone core in the center, was over 175 feet thick—nearly two-thirds of a football field. The stone core itself was over 20 feet wide and may have originally risen to a height of almost 60 feet above the surrounding plain.

The outer layer of the rampart was plastered with crushed travertine to prevent erosion of the slope. The plaster was not only impermeable to water, but it also stabilized a steep, smooth, hazardous slope which would cause an enemy to think twice before attacking the city. The builders of the rampart apparently considered a slope of about 40 degrees ideal.

In 1978, to check these conclusions, Biran decided to make a third cut into the rampart at the southeastern part of the tel, in what he calls Area K. In general, his earlier findings were confirmed.

At one point within the rampart in Area K, however, he came upon a mudbrick wall. His team of archaeologists and volunteers uncovered what they thought was a mudbrick wall which ran for a length of 30 feet in an east-west direction. Then the supposed wall turned south. This was all Biran knew at the end of the 1978 season. But this angle in the supposed wall was already enough for Biran to speculate that the structure might not be a wall but a tower—perhaps part of a gateway, he thought.

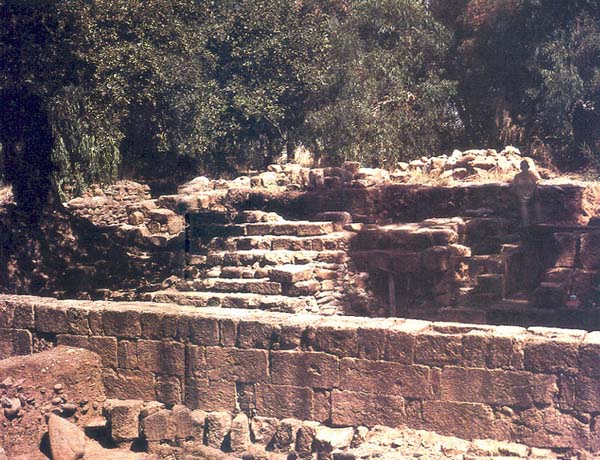

Subsequent excavation in 1979 proved him correct. What he had found in 1978 was the northern of two mudbrick towers which flanked the entranceway to Laish. In 1979 the tower was excavated to its base. It rested on a massive stone construction which guaranteed firm support for the mudbrick superstructure.

At the end of the 1979 season a staff architect was drawing a section of the just-excavated mudbrick structure. Suddenly he noticed that what he was drawing was the top of an arch. He immediately ran to the director with his drawing. Biran went to the site skeptically. How could a mudbrick arch be preserved for nearly 4,000 years, especially in a city that had seen as many wars and destructions as this one?

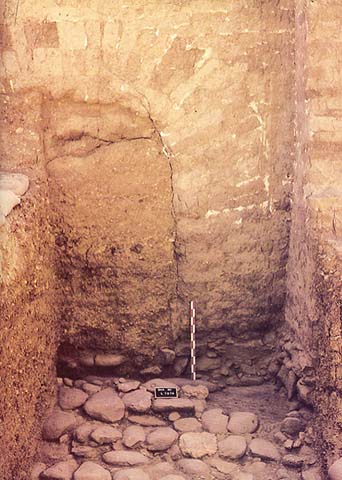

But Biran’s skepticism turned to amazement as he examined the mudbricks in situ. The mudbricks had originally been covered with white plaster. The plaster had long since disappeared except in the joints between the courses of brick where it continued to adhere, seeming to outline the bricks in white. The remains of the white plaster only emphasized the curve. There was no denying that an intact mudbrick arch had been discovered.

The next problem, which Biran postponed to the 1980 season, was how to excavate the arched gateway.

Sun-dried mudbrick begins to disintegrate as soon as it is exposed to air. It is one of the least durable materials that the archaeologist uncovers. But this was not the only problem with the mudbrick gate at Dan. At many places roots from trees on top of the tel had penetrated the mudbrick. Cracks were already visible in the part of the mudbrick tower exposed in 1978.

Another early concern was that the mudbrick arch might collapse. It turned out, however, that the Canaanites themselves had filled in the arched entranceway, thus supporting the arch, before burying the entire gateway structure within the rampart. By burying the gate within the rampart after only 30 to 40 years of use, the Canaanites unwittingly assured its preservation for nearly 4,000 years.

Biran finally decided to excavate the arched gateway in a very conservative way. He would leave half the gateway covered. The other half would be opened by digging a tunnel beneath the arch leaving a border of hard alluvial soil as a buffer between the supports of the tunnel and the mudbrick of the gate. In the summer of 1980 the gateway was penetrated by a tunnel almost six feet long. At its end the tunnel joined a guard room, to the right, within the tower. This room had previously been discovered when a deep shaft was sunk through the tower’s mudbrick.

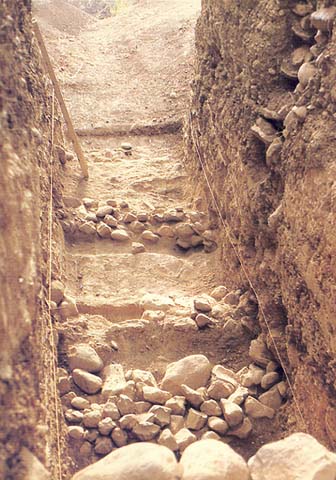

Outside the gate, the archaeologists uncovered steps that led to the valley floor below. Beneath these steps, at a depth of about one and a half feet, an earlier set of steps was found, clearly indicating that the gate had gone through at least two phases of use before it was incorporated into the rampart. This was subsequently confirmed by two thresholds which were found within the gate.

A number of questions about this remarkably preserved structure remain unanswered—perhaps we will never know the answers. Exactly when was the gate built? How long was it used? Why did the Canaanites stop using it? Why did they bury it within the rampart? How was the gate-tower complex connected to the city wall? In future seasons of excavation, Biran will be looking for the answers to those questions and others.

This unusual gateway is only the latest in a series of extraordinary discoveries at Tel Dan, including several which relate quite directly to the Bible.

As BAR readers know, Dan is mentioned frequently in the Bible. Originally, the city was called Laish (Judges 18:29) or Leshem (Joshua 19:47). When the tribe of Dan was unable to take possession of the territory allotted to it on the Mediterranean coast (Joshua 19:40–47), the Danites looked elsewhere for a place to live, finally settling in the city of Laish (or Leshem) which they conquered and renamed Dan (Joshua 19:47–48; Judges 18:27–29). Biran has identified the stratum VI city (about 1150 B.C.) as the first Danite occupation.

This stratum consists principally of pits and stone-lined silos for storage. One of these silos was over six feet deep. Twenty-nine pottery vessels were found inside it, including large storage jars (pithoi) and cooking pots. Only one plaster floor was found, however. This archaeological evidence suggests that the Danites at first lived in tents or huts, which is consistent with the reference in Judges 18:12 to mah

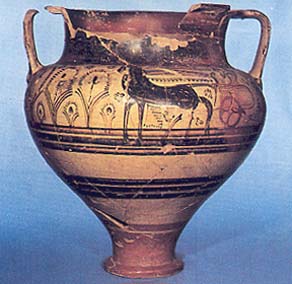

Interestingly enough, Biran has not yet found the Canaanite city which the Danites conquered. He has, however, found a magnificent tomb from that period, the Late Bronze Age (14th–13th century B.C.), which indicates that the Canaanite city, wherever it was (perhaps on the unexcavated western part of the mound), must have been large and prosperous. This unique tomb, known as the “Mycenaean tomb” because of the relatively large number of Mycenaean imports found in it, contained gold and silver jewelry, bronze swords, ivory cosmetic boxes as well as local and imported pottery. One of the Mycenaean pieces is a so-called charioteer vase, the only complete one of this type ever found in Canaan. The Mycenaean tomb contained 45 skeletons of men, women and children; apparently the bones and funerary offerings were periodically pushed aside to make room for new burials and offerings. Perhaps someday Biran will uncover the city where these long-buried people spent their lives.

Dan was the northernmost city of the Israelite tribal territories. During the Israelite monarchy Dan marked the northern border of the kingdom, which is frequently described in the Bible as extending “from Dan to Beer-sheba” (1 Samuel 3:20; 2 Samuel 24:15; 1 Kings 4:25; 1 Chronicles 21:2).

After the monarchy split in two after King Solomon’s death in 921 B.C. and Jeroboam became king of the northern kingdom of Israel, he set up two religious shrines to compete with the Jerusalem cult. One shrine was at Bethel, on the southern border of the country and the other was on the northern border at Dan (1 Kings 12:29). In each shrine Jeroboam set up a golden calf. “Here are your gods,” he told the people of Israel (1 Kings 12:28). He also set up altars and appointed priests to serve at the shrines, which are referred to in the text as beth bamoth (1 Kings 12:31). A beth bamah (plural, bamoth) has been variously translated as a hilltop shrine (New English Bible), a house on a high place (King James, Revised Standard Version, and Jewish Publication Society), a high place (Jerusalem Bible), and a cult place (New Jewish Publication Society).

High places were used for general worship purposes.”1 The most common religious practices mentioned seem to be sacrifices and the burning of incense (1 Kings 3:3; 12:32–33; 2 Kings 16:4; Jeremiah 19:3–5; Ezekiel 6:6; 20:28). In addition, people ate and prayed there (1 Samuel 9:13, 24). Biran believes he has found the remains of the beth bamah first constructed at Dan by King Jeroboam.2 Although some archaeologists have questioned this bold conclusion, there is no doubt Biran has uncovered an impressive Israelite cult place.

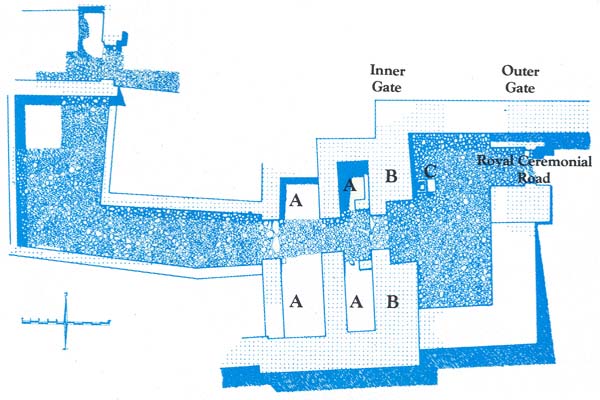

The Sacred Area or temenos at Dan is a large complex over a half-acre in size. The central open-air platform of the Sacred Area went through three phases during the Israelite period. Biran has identified the three phases of the platform as Bamah A, Bamah B, and Bamah C.

Bamah A is probably the one built by Jeroboam in the late tenth century B.C. (This Jeroboam is known as Jeroboam I to distinguish him from a later Israelite king of the same name.) Bamah A consists of an open-air platform approximately 22 feet wide and 60 feet long constructed of dressed limestone blocks on a base of rough stones. Only two courses of Bamah A have survived. It was destroyed by a fierce fire so hot that it turned the edges of the stones red. From this phase of the sanctuary Biran found the remains of incense burners, a decorated incense stand, the heads of two male figurines, and a bowl decorated with a sign resembling a trident. The bowl contained fragmentary bones of sheep, goats and gazelles which had probably been sacrificed at the sanctuary.

During the first half of the ninth century B.C. the open-air platform was rebuilt and expanded into an almost square structure measuring 60 by 62 feet (Bamah B). The masonry of this bamah, including dressed stones with bosses laid in header and stretcher fashion compares well with the royal buildings from the same period found at Megiddo, and similar buildings from Samaria. This masonry is among the finest found in Israel.

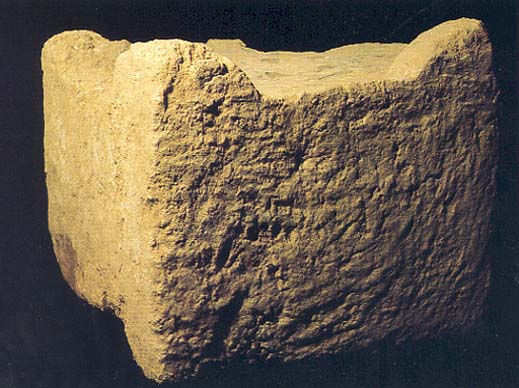

A nearly complete horned incense altar was uncovered in an adjacent court which may come from this time period. The altar, with one horn perfectly preserved, is about 16 inches high and shows evidence of long use. We may assume that many of the activities associated with the bamah, including the burning of incense, took place in courtyards surrounding the open-air platform where this incense altar was found.

The third stage of the bamah’s history (Bamah C) reflects the period of the first half of the eighth century B.C. At this time a set of monumental steps, about 27 feet long, was built against the southern face of the open-air platform. The upper three courses of these steps were added or repaired in Hellenistic or Roman times, indicating that this Sacred Area continued to be used for cultic purposes perhaps to the turn of the era. Other evidence—additions to walls and new rooms—confirms this conclusion.

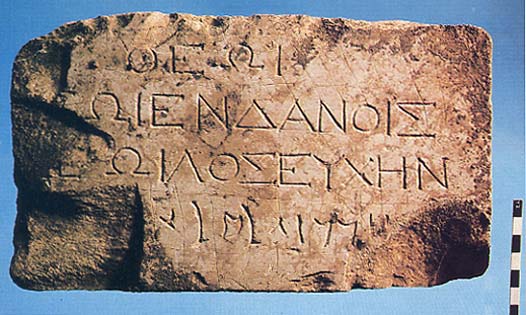

That the area remained cultic is also shown by a unique find dating to the Hellenistic period (third–second century B.C.) uncovered in the Sacred Area. In 1976 Biran uncovered a beautifully preserved votive inscription carved on a limestone slab approximately 10 × 6 inches. The inscription, three lines in Greek and one in Aramaic, refers to a person named “Zoilos” who made a vow to the “god who is in Dan” or—an alternative reading—to the “god of the Danites.” Although the Aramaic portion of the inscription has been damaged it probably reads the same as the Greek.3

With the recovery of this inscription, Dan becomes one of a handful of sites whose identification is confirmed by finding the name of the site inscribed on an artifact found there. Gezer and Hazor are two other such places.

About 70 feet south of the open-air platform Biran found, during the 1978 and 1979 seasons, a unique cultic installation which apparently involved the use of water libations. There is nothing the least bit like it in the entire Near East. In the center of this unusual installation is a sunken base which rests on a lining of pavement stones. On either side of this plastered basin two large, flat basalt slabs were laid, one to the north of the basin, the other to the south. The slabs slope gently away from the basin. At the end of each basalt slab is a sunken jar embedded up to its mouth in plaster, with its mouth pointed toward the basalt slab and the basin in the center. A groove or slit in the southern slab was carved which may have directed the water (or other liquid) into the jar at the end of the slab.a A similar channel was carved in the plaster which covers the northern slab. This entire installation is 20 feet long and dates to the tenth–ninth century B.C., the period of the Israelite monarchy.

That ancient Israelites engaged in water libation ceremonies is clear from several Biblical passages.

When Samuel assembled all Israel at Mizpah to judge them, the Israelites “drew water and poured it out before the Lord and fasted all day, confessing that they had sinned against the Lord” (1 Samuel 7:5–6).

Elsewhere, we read of King David pouring out water to the Lord, water which had been brought to him by his warriors at the risk of their lives (2 Samuel 23:16). Ezekiel speaks of drink-offerings being poured out at high places (Ezekiel 20:28).

Unfortunately, the Bible gives us no more details of these ritual libations. How the water or liquid ritual at Dan was performed remains unclear. Probably the water was ladled from the basin and poured onto the basalt slabs and flowed from there into the jars. But more than this we do not know.

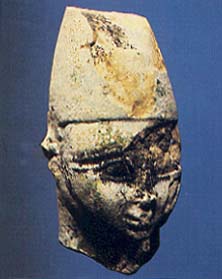

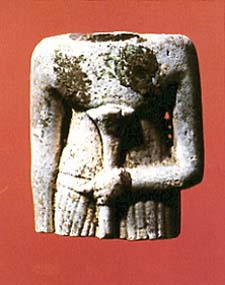

Tantalizing bits of evidence found with the water installation are difficult to interpret. For example, in the jars at the ends of the slabs, the excavators found pieces of greenish faience figurines. Other faience figurines were found nearby. The figurines reflect a strong Egyptian influence, but they were not made in Egypt. One of the figurine fragments is a head of an Egyptian pharaoh wearing the white crown of Osiris; another is a male head. Still another is a torso of an Egyptian man or god holding a staff or lotus flower. A final fragment is a monkey seated beside a standing figure holding a scepter or staff. These figurines were probably votive offerings brought to the high-place at Dan. But they do not tell us how the water system worked.

Equally mysterious are some stones found near the water installation, each with a hole pierced in one end. How were they used? We do not know.

In a room of a building near the water installation, Biran recently found a water channel which may have been used to bring water from the abundant springs in the area into the rooms for use in the water installation. If this can be substantiated in the continuing excavations, this would lend added support to the hypothesis that the early Israelites practiced a water purification or libation ritual at this unique Iron Age installation.

In any event it is clear that this entire area at Tel Dan was an important Israelite cultic center. Whether it is the beth bamoth referred to in 1 Kings 12:31, as Biran believes, will no doubt continue to be debated by scholars for years to come. Although the Biblical record is silent concerning the specific cultic acts performed at Dan and does not even specify what use was made of the Golden Calf which Jeroboam made, the archaeological evidence suggests that a large, open-air platform was used, that there were altars, incense offerings, votive offerings involving figurines, and some kind of water purification or libation rituals.

A sanctuary this large and elaborate would no doubt have attracted people far beyond the walls of Dan; this was the intention of Jeroboam I and the later kings of Israel who wanted to counter the powerful attraction of the Jerusalem cult. So Jeroboam “set one in Bethel, and the other he put in Dan. And this thing became a sin, for the people went to the one at Bethel and to the other as far as Dan” (1 Kings 12:29–30).

Mudbrick Gateway Deteriorating After Exposure

We regret to report that the magnificent intact mudbrick gateway which we featured on our cover no longer looks as it is pictured. As the archaeologists feared, the fragile mudbrick, although roofed to protect it from rain, began to crumble shortly after its exposure last summer. The stone steps leading to the threshold are mostly covered with soil from the disintegrating mudbricks and the ancient arch can be identified only by those who know where it is.

Fortunately, because of the excavator’s foresight, half of the gateway remains buried and protected by the bank of alluvial soil which was packed against it almost 4,000 years ago.

Someday a technological solution will be found for the problem of preserving mudbrick—perhaps a coating, perhaps a chemical infusion. When that capability is achieved, other archaeologists may then expose the southern half of the Middle Bronze gate so that it may stand perfectly preserved, the way its other half was seen so dramatically last year.

The Biblical Archaeology Society Preservation Fund hopes to play a role in speeding the development of techniques for the preservation of mudbrick. But the problem is not easily solved.