Inside, Outside: Where Did the Early Israelites Come From?

Before they settled in the hill country of Canaan, where did the earliest Israelites come from and what was the nature of their society?

The Bible is very clear. They were pastoral nomads who came from east of the Jordan. Much of the scholarship of the last part of the 20th century, however, has reached a far different conclusion. One might almost describe it as diametrically opposed to the Biblical account. According to this scholarship, the Israelites were originally Canaanites fleeing from the city-states of the coastal plain west of the hill country.

On one thing all scholars agree: In the period archaeologists call Iron Age I, from about 1200 to 1000 B.C.E., approximately 300 new settlements sprang up in the central hill country of Canaan that runs through the land like a spine from north to south. Almost everyone also agrees that these were the early Israelites settling down. The famous hieroglyphic text known as the Merneptah Stele, which dates to about 1205 B.C.E., refers to “Israel” at this time as a people (not a country or nation) probably located in Transjordan.

According to the Bible, Abram (later Abraham), the first Hebrew, was born in Ur, a city far east of the Jordan. Then the family “set out ... for the land of Canaan,” though they first sojourned in Haran, a site in the modern “Jezirah” of northeastern Syria (Genesis 11:27–32).

Biblical traditions also stress the close affinity of the earliest Israelites with the Arameans who lived in the Syrian desert, and not with the city-dwelling Canaanites or Amorites. When Abraham commands his servants to find a wife for Isaac, his servants head east, back to Aram-Naharaim, the city of Nahor, Abraham’s grandfather (Genesis 24:10). Rebecca, the bride they find, is an Aramean (Genesis 25:20). Likewise, Jacob’s wives, Rachel and Leah, are the daughters of “Laban [Abraham’s nephew] the Aramean” (Genesis 31:20, 24).

In the long speech of Moses that is the Book of Deuteronomy, Moses tells the people to recite before the Lord, “A wandering Aramean was my ancestor” (Deuteronomy 26:5).

The Biblical narrative is very clear as to where the first Israelites came from: outside Canaan, east of the Jordan.

The Bible is also clear as to the nature of the society from which they came. When Jacob and his sons come down to Egypt to escape the drought in Canaan, Joseph tells them that he will explain to Pharaoh that “My brothers and my father’s household ... are shepherds. They have always been breeders of livestock, and they have brought with them their flocks and herds and all that is theirs” (Genesis 46:31–34; also Genesis 47:3–4). When the Israelites leave Egypt and come to the land of Edom, they assure the Edomites they will pay for any water the Israelite cattle drink (Numbers 20:19, 32:1). In short, the Bible describes the early Israelites as pastoralists.

In 1962 George E. Mendenhall of the University of Michigan introduced a new theory of Israelite origins, however. According to him, the Israelites who settled in the hill country came not from outside, east of the Jordan, but from inside, from the Canaanite cities of the coastal plain. This massive influx of new settlers into the hill country was the result of an “internal revolt” by beleaguered peasants against the Canaanite city-states. To support his thesis, Mendenhall grossly distorted a number of passages from the Amarna Letters that mention the ‘apiru, a term often mistakenly associated with the early Israelites (see article). Empowered by a belief in their God Yahweh, the Israelites eventually withdrew from the power-centered Canaanite cities to the hitherto-unsettled hill country to the east.1 So Mendenhall.

Building on this model in a massive monograph, Norman K. Gottwald, then of Union Theological Seminary in New York, did not emphasize the role of religion, as Mendenhall had done, but explained the move to the hill country as an application of a universal Marxist paradigm. The subtitle of his book refers to “liberated Israel.” Its reasoning is informed by what the author considers a universal anthropological or sociological model: The early peasants who became Israel successfully emerged from the Canaanite cities as a result of a “peasant revolt.” The revolt was fueled not by Yahwism, as Mendenhall maintained, but by “socio-political egalitarianism.”2 The earliest Israelites, according to this theory, were really Canaanites.

To make my position clear at the outset, I have dubbed Gottwald’s theory, which has become wildly popular in academia, the “revolting peasant theory.”

The archaeological evidence to support the “revolting peasant theory” was supposedly supplied in 2003 by the well-known American archaeologist William G. Dever of the University of Arizona. Gottwald’s “insights,” Dever wrote, “have proven brilliantly correct, even if [they were] largely intuitive at the time. Gottwald was right: The early Israelites were mostly ‘displaced Canaanites’—displaced both geographically and ideologically.”3 Dever then purports to supply the firm archaeological grounding for the theory.4

Dever’s archaeological support for Gottwald’s “revolting peasant theory” comes almost exclusively from pottery analysis, one of his specialties. According to Dever, the pottery traditions of the Iron Age I hill-country settlements are developed from the Late Bronze Age Canaanite areas of the coastal plains. The proto-Israelites settling in the hill country brought with them their knowledge of Canaanite ceramic traditions, says Dever, thus demonstrating their origin.

This argument can be easily discredited, however. The same ceramic traditions have recently been found in Transjordan. Dever simply ignored the Transjordanian evidence that thoroughly undermines his contention.

To supposedly prove his point, Dever constructed a comparative table of pottery from two hill-country sites (Izbet Sartah and Shiloh) dating to the 12th century B.C.E. alongside similar pottery from three major Canaanite cities to the west (Gezer, Lachish and Megiddo) dating to the 13th century B.C.E. (the Late Bronze Age). This was intended to demonstrate the Canaanite source of the Israelite pottery shapes that appear a century later in the hill country.5

However, we have published a similar chart using as comparative material pottery from sites east of the Jordan, including the large mound of Tall al-‘Umayri, expertly excavated by Larry Herr and Douglas Clark. This new chart (constructed by Christie J. Goulart) shows the same similarities as Dever’s chart and clearly demonstrates that there is no longer any excuse to look westward for the inspiration of the surviving Iron Age I pottery shapes. The new hill-country settlers acquired their pottery traditions from their life on the Transjordanian plateau and the Jordan Valley.6

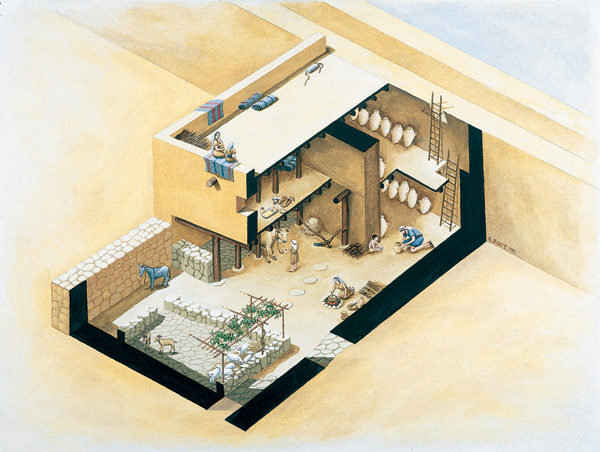

While we’re on the subject of archaeology, we may note, as does Dever, that there is also a general dissimilarity in domestic house construction between the hill-country Israelites and the earlier Canaanite cities of the plain. The famous “four-room house,” with rows of pillars that separate the long rooms (see photo and drawing opposite), that was once identified as the hallmark of an Israelite settlement is found not only at hill-country sites (and at later Israelite sites of the Iron Age II) but more recently on the coastal plain (Tel Harasim, Tell Lachish and Tel Batash).7 However, there are also examples from Transjordan at Tall al-‘Umayri and at Khirbet al-Mudayna al-‘Aliya on the southern Moabite plateau.

Another kind of archaeological evidence—the animal bones found in excavations—also tends to disprove the “revolting peasant theory”: The hill-country people did not raise pigs. In contrast, the Philistines living on the coastal plain did have pigs. Pig bones are also typical to some degree of the older Canaanite sites on the coastal plain. It cannot be argued that the hill-country areas were unsuitable for raising pigs; quite the opposite is true. If the new settlers of the Iron Age I had come from the lowlands, where pigs were domesticated and used, why did they not continue that tradition?

Conversely, the steppe land east of the Jordan would not have been conducive to pig-raising. Pigs are hard to move as “flocks,” unlike sheep and goats, which can be moved and herded quite easily. Furthermore, since pigs do not have sweat glands, they suffer terribly in the heat. On the other hand, sheep and goats, with their protective coats and grazing habits, are ideally suited to life in the steppe.

This may explain the absence of pigs in the culinary diet of the hill-country settlers; they were not accustomed to raising pigs because they did not have them in their former habitat on the eastern steppe. Indeed, the cultural/religious ideology that seems to have accompanied the prohibitions on eating pork, preserved in Biblical kosher laws, probably derives from a rejection of the values of the sedentary Canaanite and Philistine religions. In cultures around the eastern Mediterranean, pigs were sacred to the deities of the underworld and were sacrificed to them. That this was true for the Aegean suggests that it could have been equally true of Philistia.

Perhaps the most powerful arguments that the ancient Israelites came from the eastern steppe, rather than from lowland Canaan, come from linguistics, a discipline in which Dever is sadly lacking. My study of Northwest Semitic languages in the last few years, especially of the significant epigraphic discoveries made in the late 20th century,a has firmly convinced me that Hebrew has more affinities with Transjordanian languages (such as Aramaic and Moabite) than with Phoenician (that is, coastal Canaanite). And this has profound significance for the origin of the Iron I settlers in the hill country.

Although both ancient Hebrew and Aramaic borrowed the 22-letter Phoenician (Canaanite) alphabet, the fit was not quite perfect: Hebrew and Aramaic needed more consonants. Hebrew had at least 25 consonants. Aramaic had at least 26. (The consonantal repertoire of Ammonite, Moabite and Edomite cannot yet be established.) Accordingly, Hebrew and Aramaic had to make some compromises. A few letters had to do double duty; that is, they were polyphonal. The use of one sign for shin (“sh”) and sin (“s”) is the most obvious example. It would be completely illogical to suggest, as would be required by the “revolting peasant theory,” that the vast population of the newly established hill-country sites were peasants from the lowlands who had always spoken a different dialect from their Canaanite feudal masters.

The adoption of the Phoenician alphabet by the Hebrews settling in the hill country and by the Transjordanian peoples is easily explainable: The Phoenician alphabet enjoyed a high prestige in the Levant, probably because of the Phoenicians’ high degree of literacy. The rustic clans from the steppe lands to the east were so impressed by this superior cultural feature that, as they began to develop their own social and political organizations, they adopted the writing medium of the highly cultured people of the coastal areas.

The linguistic affinities between Hebrew and the Transjordanian languages evidence the common heritage of the early Israelites with other pastoral nomadic Transjordanian tribes such as the Ammonites, Moabites and Edomites, and further east, the Arameans. This area is a single isogloss, as linguists call the area of a common dialect of languages. Coastal Phoenician (Canaanite) does not share these features. For example, Phoenician and Ugaritic (a language known from the northern coastal city of Ugarit) have a different root for the verb “to be” (kwn) than that found in Hebrew, Moabite and Aramaic (hwy or hyy). Other examples of linguistic divergence include the verb “to do” and the word for “gold.”

Another significant link between Hebrew and Moabite is the use of the relative pronoun “that” (asher). It has no relationship to the Phoenician word ’is that performs the same linguistic service.

Several word sequences (or syntagmas) used to narrate sequential actions are shared by Hebrew, Moabite and Aramaic but are not found in coastal Phoenician. The most striking is the use of an archaic form for the past tense, often wrongly called the verb with conversive waw.

All this linguistic material provides a very strong argument for classifying ancient Hebrew and Moabite not as Canaanite dialects, but as Trans-jordanian languages. And this provides a nearly airtight case that the speakers of ancient Hebrew came from the same area as the Moabites, the Ammonites and the Arameans—and not from the Canaanite cities on the coastal plain.

It is ironic that the “revolting peasant theory” is supposedly based on anthropological models, while in fact a consideration of the anthropological context of the emergence of the ancient Israelites points in the opposite direction. It is clear, especially from Egyptian texts of the Ramesside period (13th–12th centuries B.C.E.), that during times of stress (especially periods of drought and famine), pastoralists like the Israelites would seek refuge in settled areas. Such behavior finds striking parallels in the activities of 19th-century C.E. Bedouin groups, as well as the movements of the Biblical patriarchs, especially Jacob and his sons. The Tigris and Euphrates Valley, the Lebanese Beqa‘ and the Jezreel Valley were, like the Egyptian Delta, all well-known refuge zones to which ancient pastoralists would turn in times of trouble.

The 13th and the early 12th centuries B.C.E. saw a new phenomenon in the hill-country areas and plateaus of the southern Levant. As we have seen, a plethora of small campsite-like settlements sprang up in the uplands of the Upper Galilee, in the Lower Galilee, in the hill country of Manasseh and Ephraim, in the hill country of Judah and in the Biblical Negev, all as documented in recent archaeological surveys. Surveys on the eastern side of the Jordan Valley indicate the same phenomenon was occurring there.8 It is in this anthropological context that the emergence of the early Israelites must be understood.

Moreover, as Dever himself has observed, coastal Canaanite sites such as Acco, Tel Keisan, Tel Yoqne‘am and Tell Qiri, as well as Megiddo, all reflect a continuity of occupation from the 13th to the 11th centuries B.C.E.9 They show no signs of a “peasant revolt.”

Another anthropological insight places the emergence of the Israelites in a still-broader context. All across the eastern Mediterranean and the Near East, there were massive invasions of the sedentary areas by outsiders at the end of the Late Bronze Age (about 1200 B.C.E.). The Libyans (with their constituent tribes or nations) invaded the Egyptian Delta. The Phrygians/Mushku invaded Anatolia. The Sea Peoples (including the Philistines, Sikels and others) destroyed Canaanite cities and settled in a long swath on the eastern Mediterranean coast, excluding the Phoenician port cities. Hordes of Arameans stormed into northern Syria and Mesopotamia. In each of these cases, a new ethnic group, fully conscious of its ethnicity, found a new homeland. In the same way, the new immigrants into the hill-country areas of Galilee, Samaria and Judea brought with them a consciousness of their own ethnic identity. There is no reason to doubt the principal assumption of the Biblical tradition that the ancient Israelites migrated as pastoralists from east of the Jordan.