The Bible tells us that the doors of the inner shrine of Solomon’s Temple had five mezuzot (singular mezuzah) (1 Kings 6:31). Whatever they were, the Bible is not referring to the little parchment texts in a case posted on the doorposts of Jewish houses that are called mezuzot. The word mezuzah is often defined as doorpost. Did this gate in the Temple have five doorposts? Hardly. But whatever mezuzot are in this Biblical text, the door to the inner sanctuary of Solomon’s Temple had five of them. The next outer gate of Solomon’s Temple had four of them (1 Kings 6:33). And the gate to Solomon palace had three of them: “And all the entrances and doorposts had squared frames, and opposite, facing each other, three times” (1 Kings 7:5, Anchor Bible).

Both the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible and the Jewish Publication Society translation drop the same footnote to the sentence describing the gate to the inner shrine with its five mezuzot: “Meaning of Hebrew uncertain.”

Just to show how difficult the Biblical passage is, we included various translations of the same verse from five different English translations of 1 Kings 6:31 (see box, “

Khirbet Qeiyafa (the Qeiyafa Ruin) is located on the northern border of the Elah Valley, about 20 miles southwest of Jerusalem. Some of the extraordinary discoveries made there have already been discussed in BAR.a The site contains the remains of a fortified Iron Age city, radiometrically dated by 27 olive pits to about 1020–980 B.C.E., the period generally attributed to King David. During seven excavation seasons, from 2007 to 2013, the Qeiyafa expedition uncovered a massive city wall, two city gates, two gate piazzas, ten Iron Age buildings, a large storage building and a central palace. Several buildings included evidence of cultic activity. In one of them (Building C10) located in the southern part of the city, a limestone shrine model was found (in Room G) smashed into dozens of pieces, together with other cultic artifacts suggesting that this room was a sacred space.

At first, the importance of this find eluded us, but after restoration—to our astonishment—there appeared a unique rare stone model of a shrine. Building models of the Bronze and Iron Ages have been discovered in the ancient Near East—more specifically Canaanite shrines, mostly made of clay. Their function was apparently to host some divine representation, and they were often decorated with figurines or animals.

The shrine model from Qeiyafa is 14 inches high, 8 inches wide and 10 inches deep. The sides and back are simple walls, but the façade is elegantly profiled. In the center of the façade is a large rectangular doorway (4 in wide and 8 in high), enhanced by three interlocking frames. These are the mezuzot. The outer frame is the largest; the middle frame is smaller and set back from the first toward the interior of the model; and the inner frame is the smallest, again set back from the first two. This triple-recessed doorframe forms three rows of lintels above the door and three rows of doorposts on either side. A fourth frame extending to the top of the structure apparently represents the edge of the building but may, alternatively, indicate a fourth, outer doorframe.

It is noteworthy that the main door of the Second Temple was 20 cubits wide and 40 cubits high, while other openings were 10 cubits wide and 20 cubits high1—in other words, with similar proportions as our shrine model. The door opening of the Qeiyafa stone model has precisely the same proportions. While this might be a coincidence, it may reflect an architectural concept of entrances to temples and palaces in the ancient Near East.

The shrine model from Qeiyafa is unusual, however. Unlike other models from the same period and region, the Qeiyafa example is not made of clay but is carefully carved from a single block of soft limestone painted in red without figurines or animal decoration. To our knowledge no such stone shrine model has ever been found before. It immediately reminded us of the entrance of the well-known Second Temple model at the Israel Museum and of Solomon’s Temple model in the Semitic Museum at Harvard University. Both models have similar gates with interlocking doorframes, that is, mezuzot.

The relationship to the Biblical text is evident. The Temple is composed of three parts: the forecourt, the outer sanctum and the most sacred part of the Temple, the shrine or devir. There is a gradual increase in the number of recessed doorframes from the entrance to the forecourt (three) to the outer sanctum (four) and finally to the entrance from the outer sanctum to the devir (five). It is as if the devir had the highest number of mezuzot because it was the most sacred part of the Temple.

To the best of our knowledge, entrances of temples in the ancient Near East, as well as from the Roman period, were usually adorned with one to three recessed doorframes, but not more. The one exception, with six, comes from a temple from the second millennium B.C.E. at Basmusian in Mesopotamia. The four and five doorframes (mezuzot) in Solomon’s Temple are exceptional and may mark a difference between the Israelite cult and religions with multiple divinities.

The Qeiyafa model shrine was found at a Judahite site—a day’s walk from Jerusalem—and dates to the time of King David, not long before the construction of the Jerusalem Temple by David’s son Solomon. The presence of a recessed doorway in the Qeiyafa model in accordance with the Biblical description of Solomon’s Temple is more than a striking coincidence. It reinforces the precision of the Temple’s description or at least shows that this architectural feature was already known in Judah just prior to the construction of the Solomonic Temple.

A second shrine model was discovered at Qeiyafa, but this one was made of clay and did not possess mezuzot. In another cultic room (in Building C3), a basalt altar was also found. A palm tree is depicted on the long sides of the altar, while on the short sides are door-like carvings with three recesses (mezuzot). Finding objects with mezuzot in cultic rooms at a Judahite site a stone’s throw from Jerusalem reinforces the importance of this feature in ancient Israelite ritual practice. The authenticity of the Biblical mezuzot in Solomon’s Temple is emphasized by the fact that they are found at a Davidic fortress in connection with religious observance at a time when the Solomonic Temple had not yet been built.

Double- and triple-recessed doorframes appear as early as the fifth millennium B.C.E. in the temple at Tepe Gawra (Ubaid Culture). Many examples are also known from the fourth to first millennia B.C.E., mainly from the ancient Near East but also in Greece and the Roman Empire. These include well-known sites such as Khafajah, Tell Asmar, Tell Brak, Ur, Mari, Alalakh and Tell Tayinat. Royal tombs from Cyprus (Tamassos) and Persepolis also feature them. In keeping with its significance, this type of doorframe was depicted on cylinder seals and on ivories representing a woman in the window. These ivories were used to adorn luxury furniture and are found in the royal city of Samaria, in the northern kingdom of Israel and in three royal capitals of Mesopotamia (Khorsabad, Nimrud and Arslan Tash). Although double- and triple-recessed doorframes are well known in the ancient Near East, they are almost entirely absent in Canaanite culture.

Interestingly enough, this tradition of multiple recessed doorframes continued in both Galilean and Judean synagogues after the Roman destruction of the Second Temple.

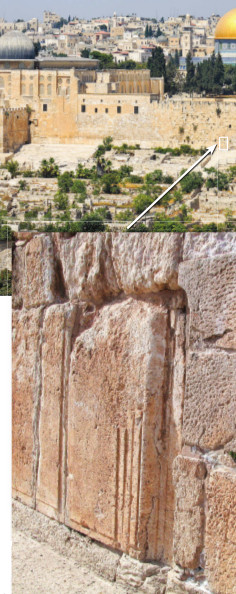

Of special importance is a surviving example from Jerusalem on the Temple compound itself. The imposing wall enclosing the Herodian Temple compound includes two sets of sealed-up gates on its southern side, the so-called Double Gate (a double-arched gate) and, farther east, the Triple Gate (a triple-arched gate). A surviving stone doorsill of the Triple Gate’s westernmost arch has three mezuzot or doorframe panels.

In our view, enhancing doorframes with recesses was meant to signify the sanctity of important buildings—to convey the message that this is God’s house; do not trespass. How did this architectural feature get from Mesopotamia and the northern Levant in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages to the southern Levant and the Qeiyafa model shrine in the Iron Age—and then to Solomon’s Temple as described in the Bible, to the compound wall of Herod’s Temple (the Second Temple) and to post-destruction synagogues?

The Bible refers to architects; Hiram of Tyre sent professionals to assist with the construction of David’s palace (2 Samuel 5:11) and, a generation later, to build the Solomonic Temple (1 Kings 5:15—24, JPS; 1 Kings 5:1—10, English). Is this explanation reasonable? It is quite possible that the Phoenician city-states of the Lebanese coast constitute the “missing link,” geographically and chronologically, between the Bronze Age building tradition of Mesopotamia/northern Levant and Iron Age Israel. Sending specialized craftsmen from one royal court to another is well documented in the ancient Near East.2

We do not know when the Biblical text describing the period of David and Solomon was composed—contemporaneously or hundreds of years later. From the Qeiyafa stone model, however, we can conclude that recessed doorframes, or mezuzot, were known in that region at that time, thus strengthening the Bible’s claim to historicity in this detail of the Biblical tradition. It seems that after about 3,000 years, the Qeiyafa model shrine has definitely solved the mystery of the Biblical mezuzot.