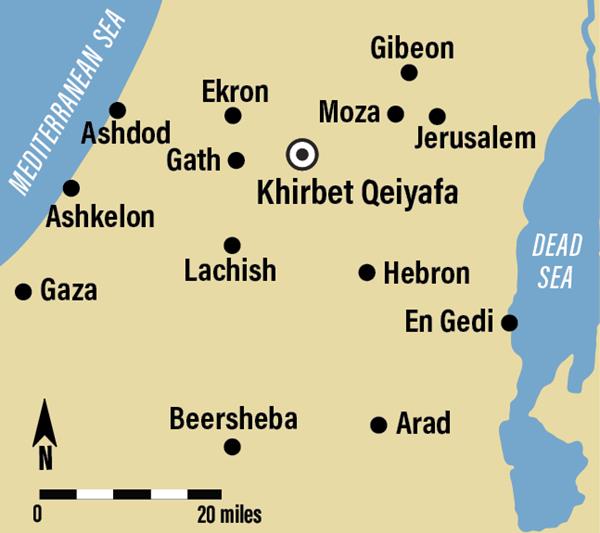

Recently three anthropomorphic male figurine heads were excavated from the sites of Khirbet Qeiyafa and Moẓa, located in the Kingdom of Judah. Two similar male heads from the antiquities market found their way to the Moshe Dayan Collection, amassed by Israel’s former legendary ministry of defense, and now appear in the Israel Museum. Together the five objects create a new type of male figurine, with three of them seeming to represent a rider on a horse. The figurines date to the tenth and ninth centuries B.C.E., the earlier period of the Kingdom of Judah. The combination of archaeological contexts, time periods, geographic distribution, iconography, Ugaritic texts, and the biblical tradition indicates that these figurines represent a male god—but which god?

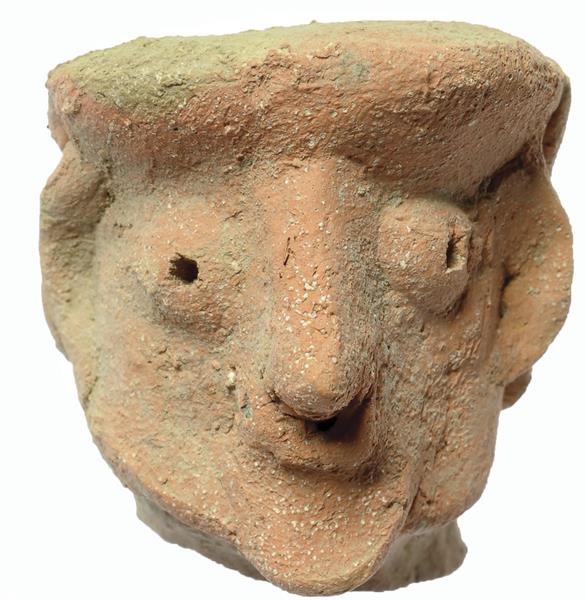

During our excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa, only one figurine was found in the early tenth-century B.C.E. fortified city. It was uncovered inside a large building in the high central area of the site. Made from clay, the figurine’s surviving head measures about 2 inches in height. Because the base of the figure’s neck is well worked, the head likely was attached to another object, either a body or a pottery vessel.

With a flat top, the head has protruding eyes, ears, and a nose. The eyes were made in two stages: They were first attached to the face as rounded blobs of clay and then punctured to create the iris. Because the ears are pierced, the figure may have worn earrings. Around the top of the head is a circle of holes.1

At Khirbet Qeiyafa, we uncovered three cult rooms with rich cultic paraphernalia—but not one human or animal figurine. The same is true for the dwelling units attached to the city wall: In about 60 excavated rooms, all covered by a rich destruction layer, not one figurine was found. So the male head is a unique discovery.

The site of Moẓa is located 4 miles west of the City of David in Jerusalem. It is adjacent to a relatively wide, fertile part of the Soreq Valley. These fields are the closest large-scale agricultural land to Jerusalem. This area must have been the main supplier of food to the nearby city in ancient times. Recent salvage excavations at the site have uncovered an important administrative center of the Kingdom of Judah, dated from the tenth century B.C.E. to the end of the kingdom in the sixth century.

Of special interest is an elongated building, 33 feet wide and at least 59 feet long—a very large size indeed! The plan is similar to that of Solomon’s Temple, with five architectural components: two symmetrical pillars in front (one of which is missing), along with a front forecourt, sanctum, and side chambers.a To the east of the building was a large open courtyard with a stone altar and a pit holding a large concentration of animal bones, pottery sherds, and broken cultic items. Additional cultic paraphernalia uncovered in the courtyard included four clay artifacts: two large male heads and two horses.

Solid and well made, the human heads have detailed facial features. They are rather square in shape with flat tops and prominent noses. The eyes were made in two stages: They were first attached to the face as a rounded blob of clay and then punctured to create the iris. The lower part of the face has a rounded bulb, probably representing the chin and a beard. A row of small punctures run from side to side on the cheek and chin, portraying a beard. Long ribbons of clay attached to the back portray hair. These male heads are very similar to the head from Khirbet Qeiyafa.

Two horse figurines were found near the heads. They were hollow, like pottery vessels. The two horse figurines and the two clay male heads have been understood as four different figurines. However, based on a zoomorphic pottery vessel from the Dayan collection, I see at Moẓa only two figurines, each representing a rider on a horse.

The zoomorphic vessel from the Dayan Collection is shaped like a rider on a horse. Liquids could be poured in through the vessel’s neck and out through a hole in the horse’s mouth.2 The human head, which is located on the neck of the vessel, ends at the top in a straight line, with emphasized ears, eyes, nose, and beard. Although the quality of craftsmanship is poor, the head is similar in style to the heads from Khirbet Qeiyafa and Moẓa. The human body is rather small and not in anatomical proportion to either the head or the horse, while the horse is relatively well modeled with anatomical parts in correct proportions. In this respect, the vessel shows that the two heads and the two horses from Moẓa could represent two horse-and-rider figurines.

Another pottery vessel from the Dayan Collection—a strainer jug with a human face—has similar modeling to that of the heads from Khirbet Qeiyafa, Moẓa, and the rider on a horse. Because both vessels come from the antiquities market, their exact provenance and context are unknown. Dayan, however, kept records of the sources of the vessels, and supposedly they came from the Hebron Hills. As the vessels are complete, they were probably looted from burial caves in that area. They were likely used for libation in cultic ceremonies and later buried with the people who used them. The vessels’ shape and decoration indicate a tenth- or ninth-century B.C.E. date.

The concept of a male god represented as a rider first appeared in Late Bronze Age Ugarit, an ancient port city on the Mediterranean Sea in northern Syria. The Canaanite god Baal is described as rkb ‘rpt, “rider of the clouds,” 16 times in various Ugaritic texts.3

The exact term also appears in Psalm 68:4. In the biblical tradition there are several descriptions, or metaphors, of the male god Yahweh as a rider, such as Deuteronomy 33:26; 2 Kings 2:11-12; 2 Kings 23:11; Psalm 45:4; and Isaiah 19:1. For example, Psalm 68:4 reads, “Sing to God, sing praises to his name; lift up a song to him who rides upon the clouds.”

Some biblical traditions, then, describe Yahweh as a rider on the sky or clouds, exactly as at Ugarit. But some texts present a new development in which he is riding on a horse. For example, Habakkuk 3:8 reads, “Was your wrath against the rivers, O Lord? Or your anger against the rivers, or your rage against the sea, when you drove your horses, your chariots to victory?” This new concept appears in iconography, too. The Canaanites did not depict a male god on a horse. Only in Iron Age texts and iconography does the horse became a divine companion animal. So the iconographic elements of the figurines correspond with descriptions of Yahweh in the biblical tradition.

It seems that another iconographic element may correspond with descriptions of Yahweh in the biblical tradition. The heads of the figurines from Moẓa and Khirbet Qeiyafa are outstanding in their large size in relation to almost all known anthropomorphic figurines uncovered—from the prehistoric era to the Iron Age. The facial elements (eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and beard) are emphasized and well modeled. The same iconographic approach is seen in the two unprovenanced vessels from the Dayan Collection, which emphasizes the head and face. This characteristic can be explained in light of the biblical expression “before the Lord,” which in Hebrew can literally be read “face of Yahweh,” a term commonly associated with pilgrimage to cult centers such as Shiloh (1 Samuel 1:22-23) and Jerusalem (see, e.g., Deuteronomy 16:16; Isaiah 1:12).

Another aspect of seeing the face of a god during pilgrimage to a cult center should be noted. As the believer sees the face of the idol, in that very moment the idol also looks at the believer. This is a metaphysical moment, a contact between earth and heaven, the core of the religious experience. This moment is also described in the Priestly Blessing in Numbers 6:24-26: “The Lord bless you and keep you; the Lord make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious to you; the Lord lift up his countenance upon you, and give you peace.”

It seems that in early times, visitors had an actual visual experience of seeing the face of the idol at a temple. This was a common practice in the ancient Near East, which is reflected in a number of cultic scenes on cylinder seals. In the same way, it was practiced in the Kingdom of Judah during the tenth and ninth centuries B.C.E. Later, probably in the eighth century B.C.E., this cult practice was abandoned, and the expression became metaphorical.

Scholars have debated the biblical theology of this aniconic aspect, as expressed in the second of the Ten Commandments: “You shall not make for yourself an idol” (Exodus 20:4). The debate centers on three main questions:

(1) Was there an actual ban on cult images during the Iron Age (c. 1200–586 B.C.E.)? While some scholars accept the existence of such a ban, others do not.4

(2) When was the biblical ban on cult images introduced and why? Was this ban already in force during the Iron Age I (c. 1200–1000 B.C.E.), or is it a much later phenomenon dating from the late seventh or sixth centuries B.C.E.—or even from the post-exilic period in the fifth–fourth centuries B.C.E.?

(3) Does the ban on cultic images reflect a local internal development or the adoption of external religious practices, primarily from Mesopotamia?

The male head figurines from Khirbet Qeiyafa and Moẓa seem to supply the following answers: There was a ban on the cult images of Yahweh. It was introduced during the eighth century B.C.E., and it reflects a local development. This is because these figurines, resembling the literature of ancient Canaan and Israel, have been discovered in contexts dating to the tenth and ninth centuries B.C.E., but not in the eighth century and afterward.